October 25, 2025

October is ‘flying” by! It seems amazing how quickly my Inktober 2025 sketchbook is filling up with daily EggTober watercolor paintings of bird eggs. Week three is now complete, and the eggs of eight more breeding birds of New Mexico can be viewed below. As with Submissions One and Two, included are a few fascinating facts about bird eggs, this time with a focus on the eggshell.

In case you missed my first and/or second EggTober posts, and would like to catch up, click the following link(s) to read Submission One, and/or Submission Two.

A Bird’s Eggshell

At first glance, you may think all bird eggs are covered in a hard, solid shell. You would be right about the shell being hard, but have you ever taken a close look at the shell surface? The outer shell appears to have dimples, a bit like a golf ball. Those dimples are pores in the eggshell. Bird eggs are considered “amniotic” which means their eggs not only have a hard shell; they have a porous membrane to allow for oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange. Also, an important characteristic of amniotic eggs is they resist dehydration, which is why birds can lay them on dry land. So, is the porous membrane sandwiched between the eggshell and the ‘egg white’ (albumen), and why?

In Submission Two, I noted that the typically oval-shaped bird egg is able to withstand the weight of the incubating parent(s); the shell having the strength and resilience to withstand external pressures which minimizes the chances of the developing embryo becoming deformed or suffering bone fractures. So, just how thick must an eggshell be, yet still allow the developing embryo to breathe?

What are the main functions of the eggshell?

The shell of an egg contributes to successful formation and development of the embryo, by providing protection, respiration and water exchange. The eggshell is also the major source of calcium for the development of high-calcium consuming organs, like the skeleton, muscles and brain.

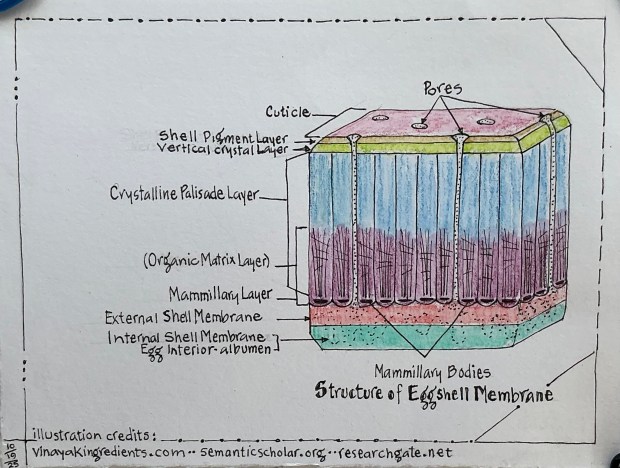

But what we think of as the eggshell, is actually Eight Separate Layers (!) that stack together from the outside of the egg to the inside where layer eight meets the albumen. It’s through these layers that the embryo breathes.

These layers, from the outside in, are the Cuticle layer with Pores, Shell Pigment layer, Vertical Crystal layer, Crystalline Palisade layer, Organic Matrix layer, Mammillary layer with Mammillary Bodies, External Shell Membrane layer, and Internal Shell Membrane layer. These will be summarized below. I’m also compiling a more complete description of each layer and detailing their importance, which should be complete and posted before the end of the month.

But before taking a brief ‘look’ at the eight eggshell layers, I wanted to share a snapshot about their thickness ….. because, quite frankly, I couldn’t imagine how all those eight layers manage to fit!

Eggshell Thickness

Most bird eggshells must be thin enough for the chick to peck through when it hatches, but at the same time it must be thick enough to bear the weight of the growing embryo inside, and the weight of the parents incubating it. The thickness of eggshells varies among species and individual birds, but also among individual eggs laid in a clutch. Eggshell thickness is also influenced by factors like the bird’s age, diet, and where the measurement is taken on the egg. In general, bird eggshells are usually 5% thicker at the mid-section of the egg (the area called the equator) than the ‘bottom’ (the sharp egg pole) and ‘top’ (the blunt egg pole) ends.

To ‘illustrate’ how thickness varies by a few species, the egg of a Blue-tailed Emerald (a species of hummingbird that lays an egg with one of the thinnest recorded eggshells among all bird species) has a shell that’s 0.029 mm (0.0011 inch) thick. Compare that with an Ostrich egg, the largest egg with the thickest eggshell in the world, measures in at 1.92 mm (0.08 inch) thick. For many common species, like the Mallard, shell thickness is around 0.337 mm (0.013 inch); a domestic chicken eggshell varies from 0.33 – 0.36 mm (0.013 – 0.014 inch) thick.

It may be helpful to relate these small sizes in eggshell thickness to an average human hair, which can be anywhere from 0.06 mm (0.0024 inch), to 0.10 mm (0.004 inch) thick. I’m still amazed how an eight-layered eggshell happens!

Structure and function of eggshell layers: Cuticle layer and the Pores, Shell Pigment layer, Vertical Crystal layer, Crystalline Palisade layer

Cuticle (aka Bloom)

The Cuticle’s primary functions are to act as a physical and chemical barrier against invading microbes, protect the eggshell pores, and regulate the exchange of gas (Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide) and moisture (water vapor). The Cuticle also affects the egg’s wettability, which helps prevent water and bacteria from entering, and fine-tunes the eggshell’s appearance, including ultraviolet (UV) reflectance.

Eggshell Pores

The texture of the outer eggshell is due to the Pores that form openings in the Cuticle. Depending on species, there can be anywhere from 7,500 to 17,000 Pores covering an eggshell, most located at the blunt end of the egg (the top end where the air cell is located). Each Pore is connected to a Vertical Pore Canal that penetrates the next five eggshell layers, down to the External Shell Membrane. The shells of most bird eggs have simple, straight pore canals that widen slightly toward the openings through the Cuticle. The exceptions are found in swans and the ratites (the group with ostriches and emus), where their Vertical Pore Canals are highly branched. Covering the exterior opening of the Pores of all bird species (except pigeons and doves [hmmmm ….. wonder why]) are tiny plugs or caps, which may act as pressure-sensitive valves.

The Pores and their canals provide a critical passageway for gas and moisture exchange between the inside and outside world. This exchange allows the developing embryo to breathe by taking in oxygen and releasing carbon dioxide and water vapor.

Shell Pigment Layer

The Shell Pigment Layer serves multiple critical functions, including camouflage, thermoregulation, and protection for the developing embryo. The colors and patterns come from two main pigments, protoporphyrin (brown/red) and biliverdin (blue/green), and their function varies depending on the bird’s environment and nesting behavior.

Vertical Crystal Layer

The Vertical Crystal Layer provides mechanical strength and structural integrity. Its tightly packed, vertically oriented crystals form a dense, outer layer that protects the embryo from physical shocks, while also being integrated with the Palisade Layer (below) to form a tough, ceramic-like structure. This outer layer’s density and arrangement make it resistant to impact.

Crystalline Palisade Layer

The Crystalline Palisade Layer serves two primary functions: providing mechanical strength and regulating gas exchange for the developing embryo. This is a thick, mineralized layer, that forms a dense matrix of calcium carbonate crystals, and is critical for protecting the egg’s contents while also aiding metabolic processes (i.e. all the chemical reactions within the embryo that are essential for life).

Structure and function of eggshell layers: Organic Matrix layer, Mammillary layer with Mammillary Bodies, External Shell Membrane layer, and Internal Shell Membrane layer

Organic Matrix Layer

The Organic Matrix Layer plays a crucial role in controlling biomineralization, forming the shell’s microstructure, and providing antimicrobial defense. Consisting of proteins, glycoproteins, and proteoglycans, this layer acts as a scaffold that controls the eggshell’s strength and protective properties.

Mammillary Layer and Mammillary Bodies

The Mammillary Layer and Mammillary Bodies form the foundation for the rest of the eggshell. Their primary function is to provide the calcium for the embryo’s skeletal development. This inner layer is composed of calcite microcrystals that dissolve easily, allowing the embryo to extract about 80% of its calcium needs before hatching.

This layer also helps during the “pipping” process because its globular texture makes it easy to crack and break through the shell from the inside. Pipping is the,process where the chick breaks through its eggshell to hatch. There are two phases during pipping: internal and external. Internal pipping is when the chick breaks through the Inner Shell Membrane Layer (see below) to reach the air cell and take its first breath followed by chirping! This first phase not visible from the outside and can take 12-24 hours. External pipping is when the chick uses its egg tooth to peck a visible hole or holes in the eggshell, a process that can take a few hours to a few days, requiring the chick to rest frequently… those outer layers of shell are hard. The long time due to the chick needing to rest This can take anywhere from a few hours to a couple of days. The final step is “zipping,” where the chick turns in the egg, cracking the shell into two halves to fully hatch.

External Shell Membrane Layer

The External Shell Membrane Layer functions primarily as a barrier to protect the egg’s contents from bacterial invasion and to prevent moisture loss. This membrane is made of proteins and acts as the first line of defense after the Cuticle, preventing microorganisms from entering the egg.

Internal Shell Membrane Layer

The Internal Shell Membrane’s primary functions are to provide a barrier against bacterial invasion and to support the formation of the hard eggshell. It also helps prevent excessive moisture loss while allowing gases to pass through, a process that becomes more significant when the External and Internal Shell Membrane Layers separate to form an air cell.

Summary

Eggshells! I never knew they are such complex structures with many unique features. And eggshells are unfathomably critical to the development and survival of the embryo right up until the moment they “Pip” their way into the world. Without their bioceramic characteristics, microscopic pores, front-line bacterial defense systems, color patterns, and their surprising strength despite the shell’s thinness. birds might be something completely different or perhaps might not ‘be’ at all. Something worth pondering!

Hope you have enjoyed Submission Three of EggTober! If so, please leave me a comment. And as always, thanks for popping in!

p.s. Stay tuned for Submission Four, landing in your in-basket next week!

Dang it, Barb. Every time I think I’ll “just give this a quick read-through,” you draw me into the details. LOL! Thanks for the information. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Awesome, awesome, awesome comments, Lisa! Thanks so much. Can’t tell you how thrilled I am you were drawn into the details of eggshells.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So Fascinating!! Thanks for sharing!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the great reaction/comment! And thanks for following. Eggshells are very cool!

LikeLike

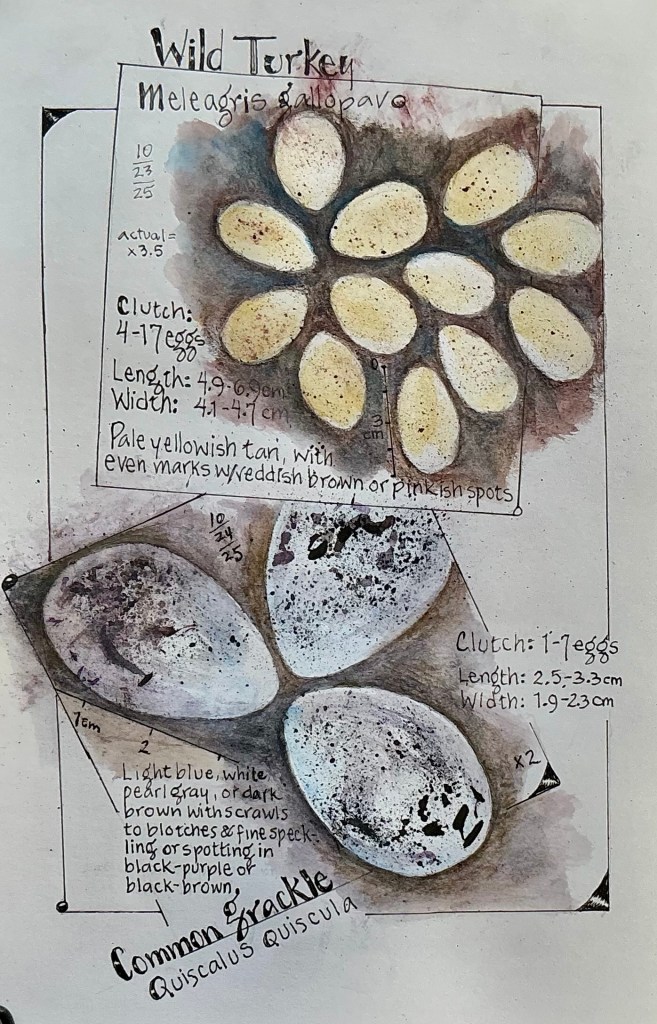

Fascinating, Barb! I can’t imagine all those layers in the thin shell, either! And, how important they are for chick development. Wow, wild turkeys can lay up to 17 eggs?! Such a fascinating study! Thanks for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Karen! Loved your comments and reactions! And I Know! All those layers is a fact that’s definitely hard to wrap my mind around! We’ve seen huge flocks, coveys, parades of turkey-lett, but never 17! That would make for a busy and exhausted mom! Thanks for following EggTober!

LikeLiked by 1 person