August 27, 2024

Webster’s had it “right on” when describing the Ubiquitous Plant Gall!

gall /ga:l/ 1. something irritating; rude. 2. not able to understand a behavior is unacceptable.

—-the boldness of these guys; the sheer gall and effrontery; the chutzpah; the unmitigated gall; What gall!

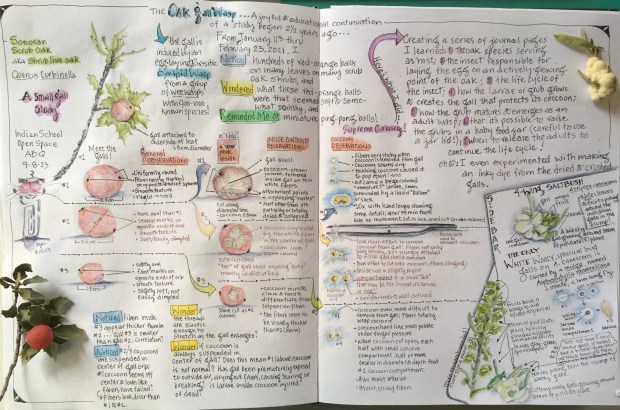

“Yeah ….. What Gall is This?!”

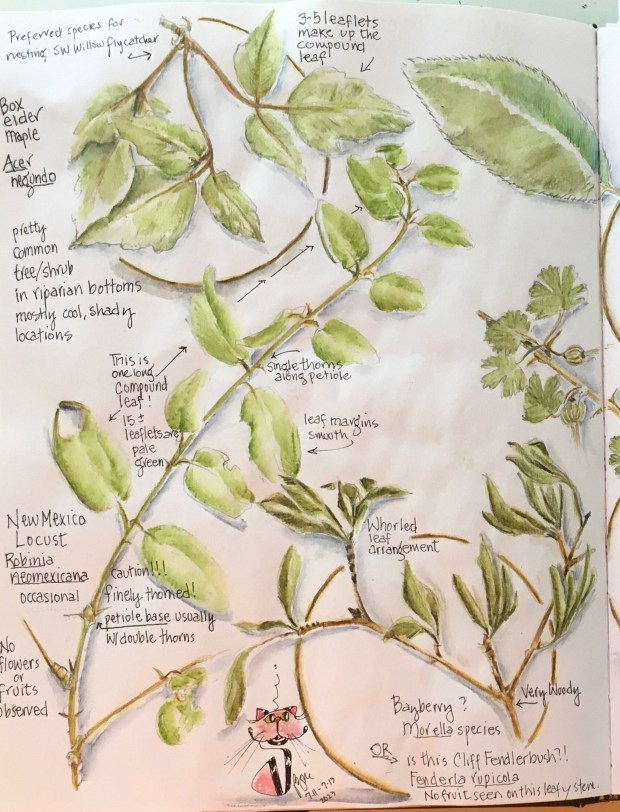

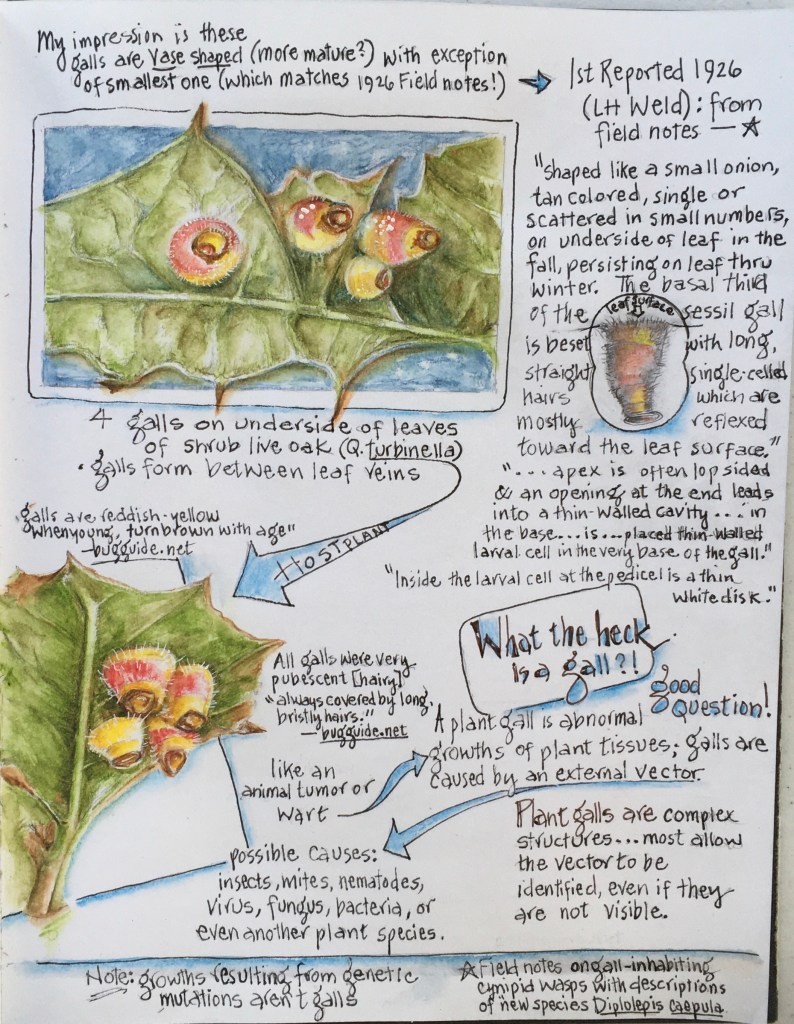

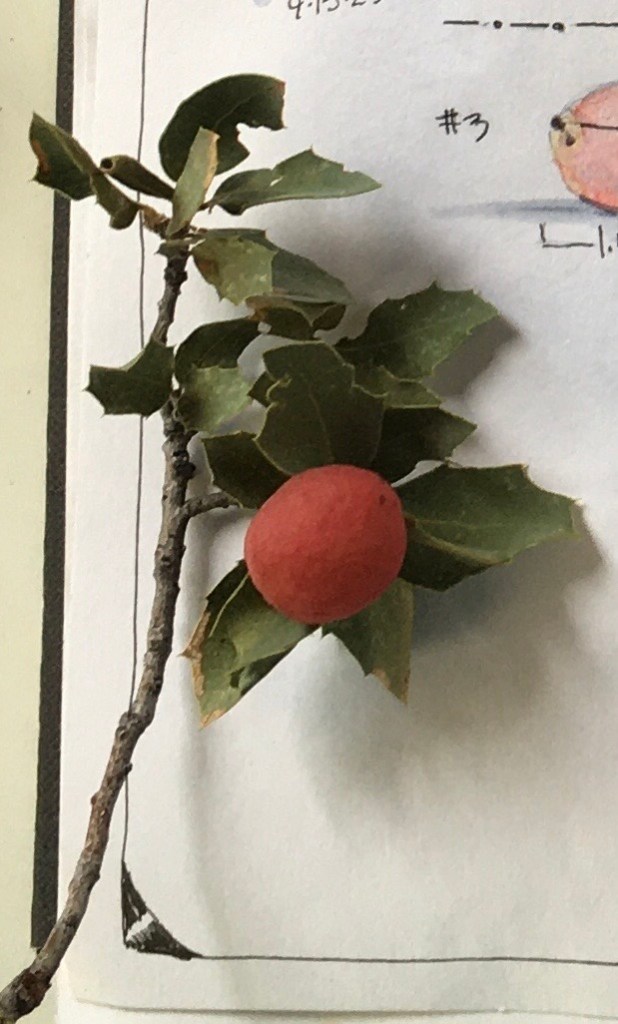

That was the question uppermost on my mind when a slight breeze wafting down the trail lifted a fresh oak leaf revealing four slightly wonky vase-shaped growths. One was squatty and pale; three were colored with alternating bands of cadmium yellow and deep vermillion. All four galls were attached to the underside of the leaf, hanging upside down, so whatever might’ve been inside is out.

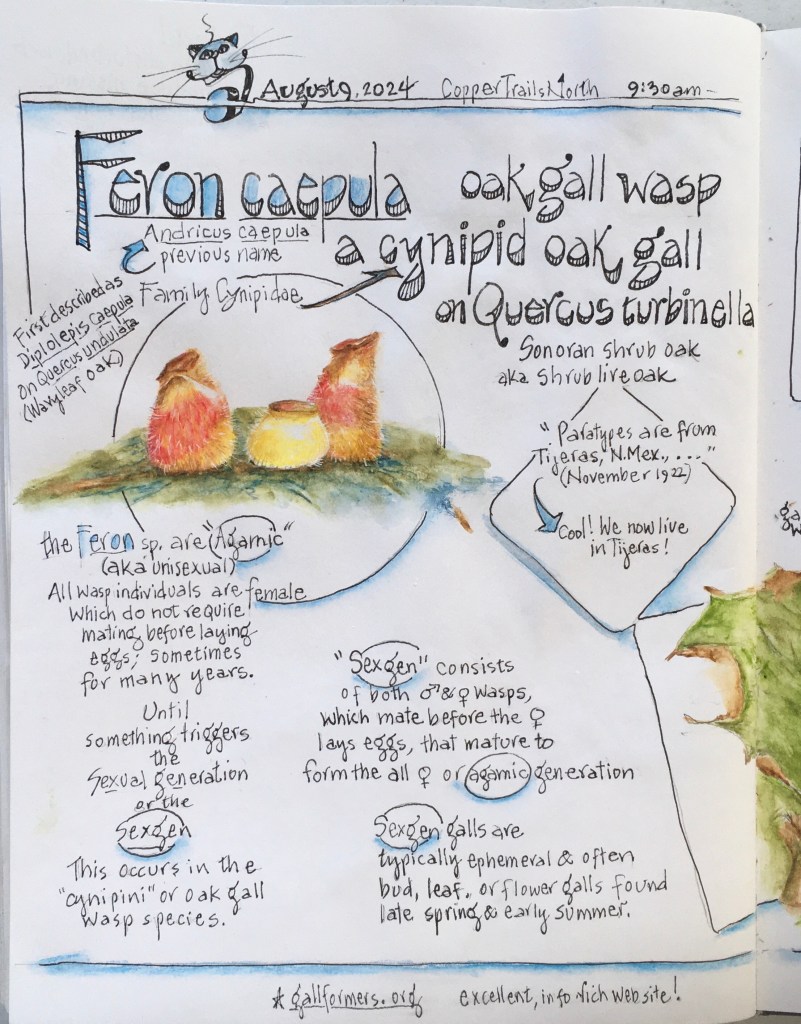

After 5 minutes of inspection ….. poking and prodding, and peering inside the tiny vases ….. I took some photos to post on iNaturalist to figure out this little mystery. It didn’t take long before my discovery was identified! These are galls of the parasitic cynipid wasp called Feron caepula, formed this Spring on a new leaf of Shrub Live Oak (Quercus turbinella).

Originally identified in a 1926 field report as a new species, Diplolepis undulata, this species’ name was reestablished as Feron caepula in a report published in 2023. Ordinarily I choose to only cite a field report, but decided to make an exception in this case for several reasons…… the description of this new species was helpful in better understanding my specimens, and……. one of the paratypes used to describe the new species came from Tijeras, NM (which happens to be my home!). So the entire 1926 field report* (surprisingly short) by LH Weld is added below.

Supplement to the Nature Journal Pages

A Curiosity of Oak Galls, Revisited …… Part III

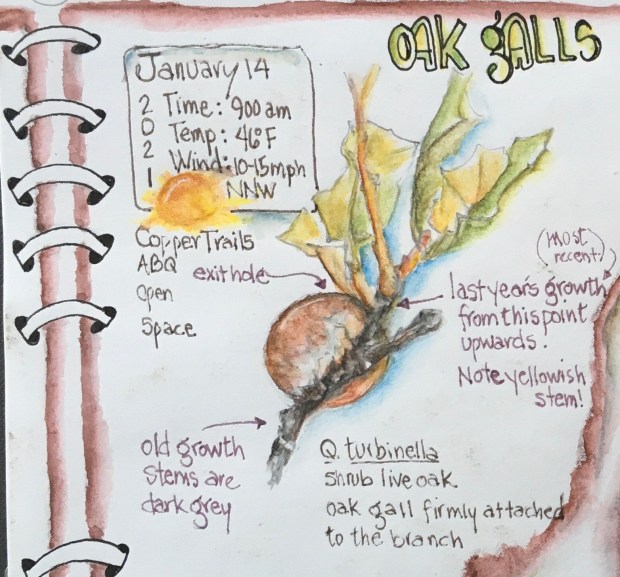

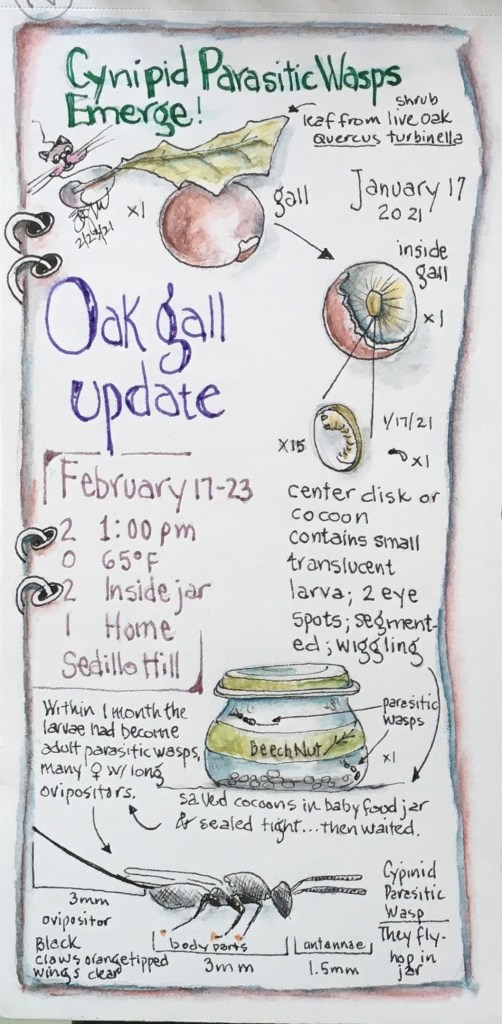

Curious about plant galls for decades, I finally began reading and experimenting to learn a bit about the inner world of oak galls. Throughout the winter of 2020-2021, I enlisted Roy’s help to collect about 100 nickel diameter, reddish-brown galls hanging on oak leaves like holiday decorations. Not knowing what to expect, I cut into a bunch of these galls and found tiny squirming grubs (larvae) – one/gall. The grubs seemed to be suspended by a complex network of stringy plant tissue radiating from each larva at the center to the inner gall shell. It reminded me of a snow globe frozen in time! Of course I had to know what these guys would become. So I placed about half of the galls into glass jars, and the other half went into jars without their protective gall home. In a few weeks the jars were full of the smallest wasps ever! Wasps! Little parasitic cynipid gall wasps active and ready to be released back into the wild to do what these wasps do! (Rest assured, they were releases in the same area where the galls were collected.)

A few years later, I was once again smitten by these tiny wasps and their galls, and learned more about their life cycle and other facts about galls in general. You can read all about my earlier experiences (and my efforts with experiments) in 2021 and 2023 at this post “No Small Galls this Fall! Oak galls, then and now, the sequel”.

Back to the Present

Here it is 2024, and while hiking the Albuquerque foothills, a new (to me) and colorful gall form appeared hanging beneath an oak leaf. My curiosity piqued. It was high time I gained some insight about the life cycle of cynipid gall wasps. Paraphrasing numerous expert sources, my attempt to interpret and understand what has been described the one of the most complicated life cycles known in the animal kingdom, still seems confusing. Maybe it’s been hard to wrap my mind around Parthenogenesis (asexual reproduction)***….. a key component of a cynipid gall wasp’s life cycle. By taking my time (over a month), and after many written and diagrammatic iterations, I stitched together a description that works. If you’re curious, read on!

Where do Oak Galls Come From, and Why?

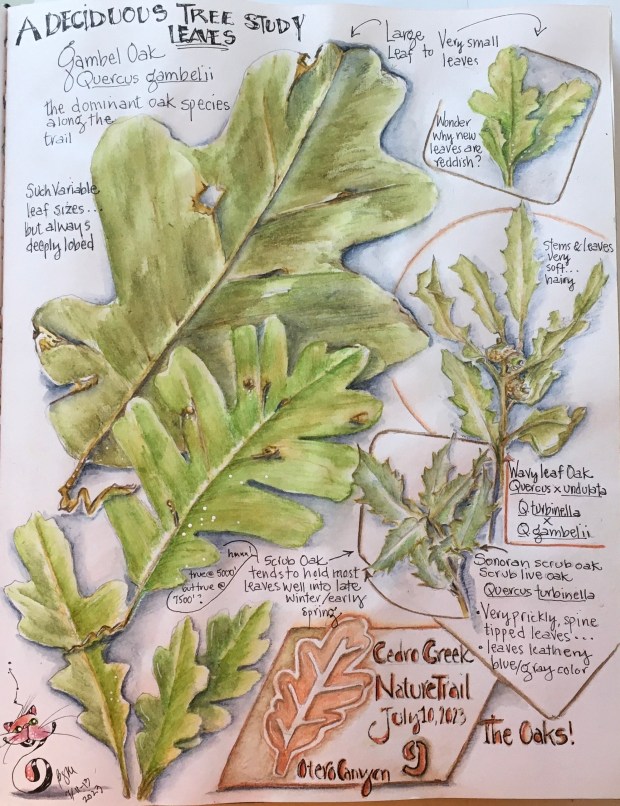

Every year in late-Spring and through early Summer our shrub live oaks (Quercus turbinella) are a-buzz with a cloud of nearly microscopic cynipid gall wasps that have emerged from a hundreds and hundreds of leaf galls. These often weird looking abnormalities begin forming during an oaks’ accelerated growth period in the Spring. “But where do galls come from and why?”

It’s Complicated!

In the case of cynipid gall wasps, the majority of more than 1400 known species* parasitize oaks, while a much smaller number favor rose and chestnut as host plants. Where and how a gall forms on a host plant, along with the gall’s size, shape and coloring is vector-specific. This gall uniqueness makes it possible to identify what species of insect, such as a cynipid gall wasp (or other external vector like a mite or virus or nematode or fungus or virus or bacteria) was responsible for each gall.

The life cycle of cynipid gall wasps alternate between asexual and sexual generations. This process, called Cyclical Parthenogenesis, is both fascinating and baffling. Typically, the gall formed by the females of the sexual generation (sexgen) shows itself in late winter/early spring, and is on a different part of the oak (such as a twig or stem) than the later asexual (or agamic) generation (agamic galls usually appear on actively growing plant tissues). The following is what appears to happen during the ………………

Lifecycle of a Cynipid Gall Wasp

The Asexual (Agamic) Generation

When the weather warms in late winter, an all-female generation of cynipid gall wasps emerge from galls which developed and became dormant the previous year, well before the cold and snow set in. This asexual generation of wasps initiates late Spring/early Summer gall development by inserting (with its ovipositor) an egg along with a maternal secretion from the venom gland, into a swollen leaf bud of the host oak. Egg laying takes place as the growing (meristematic) tissues inside the bud rapidly develop. The egg quickly hatches, and the larva begins feeding, all the while exuding specialized growth hormones that stimulate exaggerated tissue growth resulting in structures (the galls) that are visibly different from normal plant tissues. It’s during the Spring/Summer that developing galls are readily seen, often on the undersides of new leaves.

The safely hidden larva continues to eat the nutrient-rich plant tissues forming inside the gall and grows quickly until it develops into a pupa. After a few weeks in this pupal stage, an adult cynipid gall wasp has formed. Still tucked away, the adult (which is either a male or female) chews a small hole in the gall and emerges to mate.

The Sexual Generation (aka “Sexgen”)

With the business of mating taken care of, and with no mouth parts to eat, the males quickly die, followed soon by the females. However, before the females die, they deposit one or more eggs on a leaf or within a twig or stem of the host plant. Before the plant’s growing season concludes, the eggs have hatched, larvae have eaten and grown within their individual galls, and have pupated in preparation for over-wintering. Depending on the length and/or severity of winter where these cynipid gall wasps live (and they can live nearly anywhere worldwide), the dormancy period may last from three-five months.

And now …. back to the emergence of the Asexual or agamic generation (the females), in an on-going cyclic loop that is the life cycle of the cynipid gall wasp.

A Supplement to the Supplement!

Types of Galls

Leaf galls

- Form on leaf blades or petioles (leaf stems)

- Most common galls appear on the upper or lower leaf surface, on or between leaf veins.

- Galls may look like leaf curls, blisters, nipples or hairy, felt-like growths.

Stem and Twig Galls

- Deformed growth on stems and twigs.

- Range from slight swelling to large knot-like growth.

- When seen, may be peppered with many tiny holes where the adult gall wasps have emerged.

Bud or Flower Galls

- Deformed size and shape of buds or flowers.

Fun Facts

- Galls are growing plant parts and require nutrients just like other plant parts.

- A gall keeps growing as the gall former feeds and grows inside the gall.

- Once galls start to form, they continue to grow even if larvae die.

- Most galls remain on plants for more than one season.

- Galls are usually not numerous enough to harm the plant and control is not warranted.

- Gall numbers vary from season to season.

- Typically, plant galls become noticeable only after they are fully formed.

- The asexual generation (agamic) galls are reported more often because they are larger and persist longer than the sexual generation (sexgen) galls.

- Mature plant tissues are usually not affected by gall-inducing organisms.

- Iron gall ink, which was the most common ink used from the Middle Ages to the 19th century, was used in line drawings by DaVinci, Van Gogh, and Rembrandt, and in the writing of many historical documents like the US Declaration of Independence.

It’s been so helpful to study the life cycle of these tiny parasitic cynipid wasps, if for no other reason than to admit my understanding remains basically rudimentary, and I must keep my Curiosity alive!

As always, thanks for stopping by!

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

*Field report from 1926 by LH Weld

Diplolepis caepula, new species

Host. — Quercus undulata [Wavyleaf oak, Quercus x undulata]

Gall. — Shaped like a small onion, tan-colored, single or scattered in small numbers on under side of leaf in the fall, persisting on the leaf through the winter. The basal third of the sessile gall is beset with long straight single-celled hairs which are mostly reflexed toward the leaf surface. The conical apex is often lop sided and an opening at the end leads into a thin-walled cavity in which are a few scattered hairs and in the base of which is the transversely placed thin-walled larval cell in the very base of the gall. Inside the larval cell at the pedicel is a thin white disk.

Habitat. — The type is selected from a series from galls collected November 14, 1921, near Hillsboro, N. Mex., the flies emerging April 5-25, 1922. Paratypes are from Tijeras, N. Mex., and of the adults cut out of the galls on November 1 some lived in a pill box until December 28. Other paratypes are from Blue Canyon west of Socorro, adults being cut out of the galls on January 2. ….. Similar galls were seen on Q. grisea at Magdalena, N. Mex.

- LH Weld: (1926) Field notes on gall-inhabiting cynipid wasps with descriptions of new species”

Reference: https://gallformers.org

**The 1400 known species of cynipid gall wasps have been identified worldwide, with an estimated total of more than 6,000 species. In the U.S. there are over 2,000 known species of gall-inducing insects, including 750+ cynipid wasps (500 of which are found in just the West). Worldwide, entomologists have estimated that there are over 210,000 gall-inducing insects yet to be identified!

*** Parthenogenesis is a form of asexual reproduction where an egg develops into a complete individual without being fertilized. The resulting offspring can be either haploid or diploid, depending on the process and the species. Parthenogenesis occurs in invertebrates such as water fleas, rotifers, aphids, stick insects, some ants, wasps, and bees. Bees use parthenogenesis to produce haploid males (drones) and diploid females (workers).

Some vertebrate animals, such as certain reptiles, amphibians, and fish, also reproduce through parthenogenesis. Although more common in plants, parthenogenesis has been observed in animal species that were segregated by sex in terrestrial or marine zoos. Two Komodo dragons, a bonnethead shark, and a blacktip shark have produced parthenogenic young when the females have been isolated from males.