National Diatomaceous Earth Day

Part 2 – The Sequel

January 2, 2026

While Diatomaceous Earth (DE) may sound familiar to you (if not, read all about this chalky, gritty powder in my Part 1 – Diatomaceous Earth post), did you know it’s a product of millions of years old, long-deceased and fossilized Diatoms? Whether or not you’ve heard of diatoms, prepare to be wowed by these tiny little, microscopic ecological marvels! Diatoms may be the primary ingredient found in DE, but as living organisms they are so much more.

Having discovered a bounty of eye-popping information about and related to diatoms, I thought it would be best presented in digestible doses. So throughout this month, diatom posts will address some of the things I wondered about and explored when studying living diatoms, the “Jewels of the Sea!”

In this post, Part 2, I’ll discuss and/or try to answer the following questions:

What are diatoms …. plant, animal or mineral?

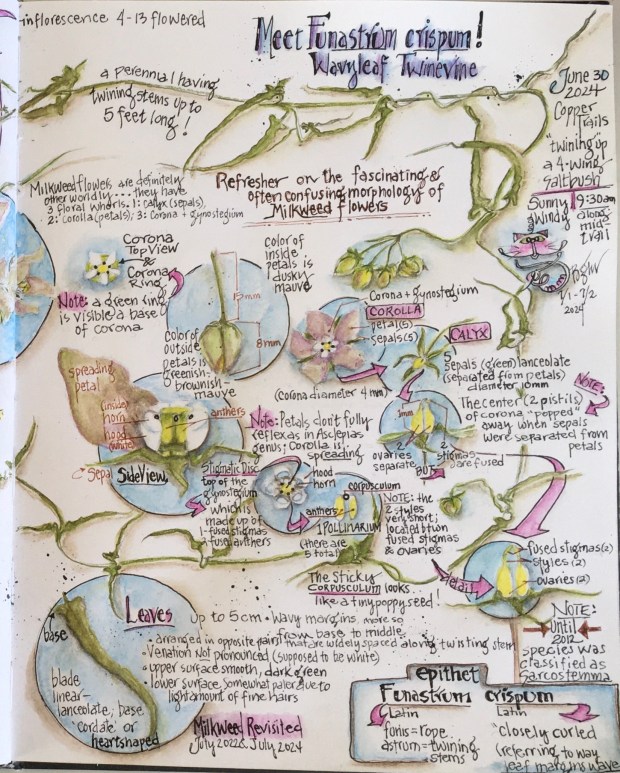

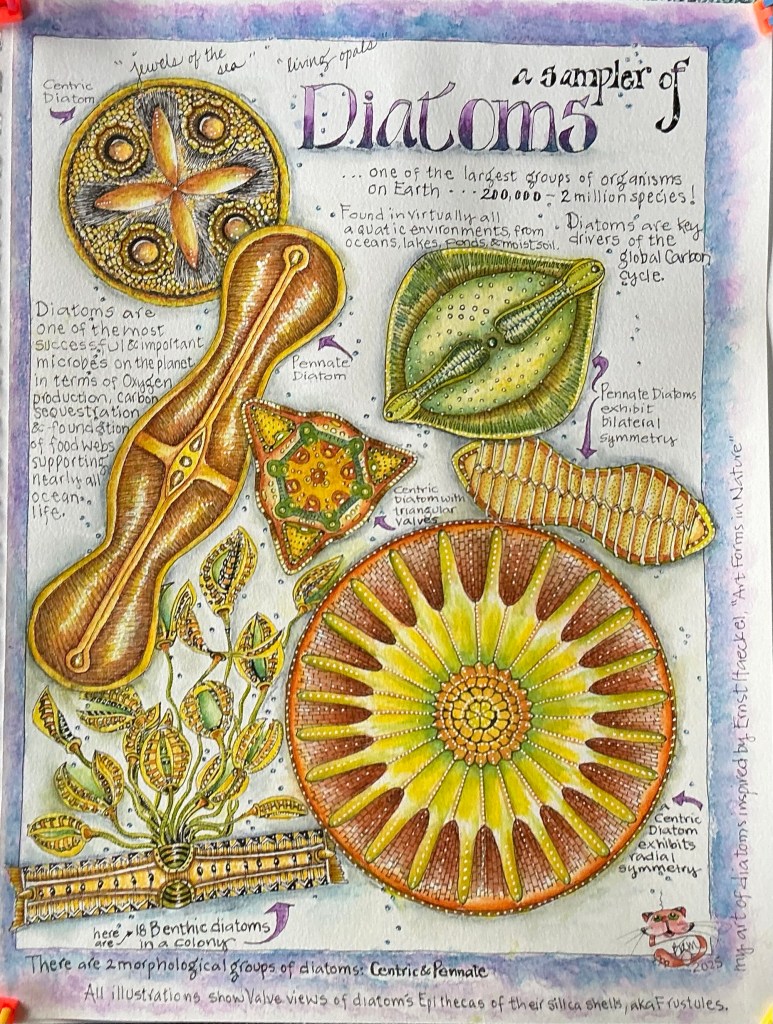

Why the nicknames, “Jewels of the Sea” and “Living Opals?”

What do they look like?

How big are diatoms?

Where and how do they live?

How many species of diatoms are there?

So come take a deep dive, if you dare, on my continuing journey into the fascinating world of living Diatoms!

What are Diatoms …. Plant, Animal or Mineral?

“… a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma…”

Winston Churchill used this phrase in an October 1939 radio speech to describe something difficult to comprehend. He could’ve been referring to diatoms.

Diatoms are the very definition of an “enigma.” How can algae, be anything other than a plant? How can algae with obvious plant-like features also exhibit animal-like characteristics? How can one of the most abundant minerals in the Earth’s crust, silica, be sculpted into elegant protective shells (frustules) surrounding these algae? These Diatoms? How is it possible diatoms, single-celled microscopic algae, are neither plant nor animal nor mineral, but are perfectly content and even thrive sharing biochemical features of all three?

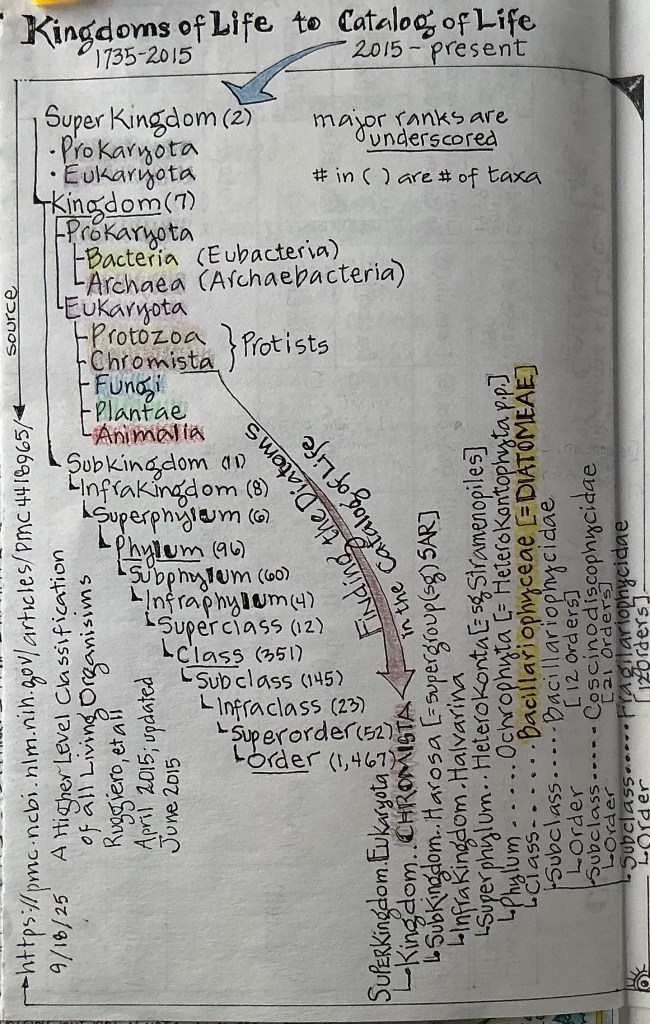

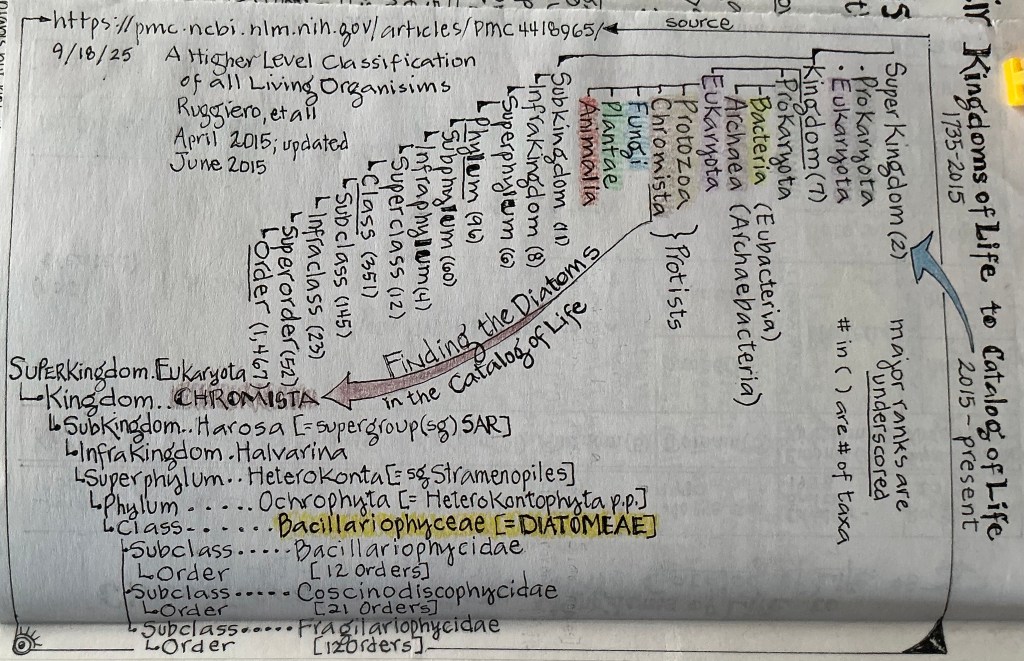

But my months-long look into living diatoms convinced me these single-celled microscopic algae (a microalgae) have earned their place as members in the Super Kingdom Eukaryota, along with animals, plants, fungi, the protists (such as algae [like seaweed; here’s where diatoms fit], amoebas and slime molds). Eukaryotes, unicellular or multicellular organisms, are considered complex when it comes to the Protoplast, the living contents of their cell(s). The Protoplast includes the cell membrane, cytoplasm, a large central vacuole, and membrane-bound organelles like the nucleus, mitochondria, Golgi bodies, one or more chloroplasts (in plants), and specialized structures like the silica deposition vesicle (where a diatom’s silica shell [frustule] is built). The Eukaryotes represent a major group of life on Earth.

So how did such a vast group of organisms, the diatoms, end up being partly plant-like and animal-like, as well as mineral-like? It’s about evolution …..

….. Diatom Evolution

Scientists have analyzed the genes and the proteins they encode, confirming that diatoms have had a complex history. Like other early microbes, they apparently acquired new genes by engulfing microbial neighbors. Perhaps the most significant acquisition was an algal cell, which provided the diatom with chloroplasts and the ability to photosynthesize. It’s been hypothesized that diatom ancestors branched off from an ancestral microbe with a nucleus, from which plants and animals later arose. As diatoms, plants, and animals evolved, each must have shed different genes from this common ancestor. As a result, diatoms were left with what looks like a mix of plant and animal DNA.

But what about that unique, silica-based frustule; a crucial part of the puzzle that so effectively protects the diatoms’ internal components while it’s alive, and plays an equally important role upon the death of all diatoms?………

….. Diatom Evolution: phase 2

Diatoms didn’t “learn” to synthesize silica but evolved a complex, genetically controlled biological process called biosilicification. This process uses specific proteins (silaffins and polyamines) to uptake dissolved silicic acid from water and precisely assemble it into intricate, ornate silica shells (frustules) within the Silica Deposition Vesicle, a feat of natural nanotechnology. This allowed diatoms to master frustule construction, making them successful in aquatic environments.

It’s true that diatoms are:

- a little bit “plant.” They have pigments in their chlorophyll that capture and convert sunlight into energy (sugars) through the process of photosynthesis. They use the genetically-controlled process of biosilicification to grow and assemble their unique and intricate silica frustules, similar to the way other plants, sponges, (and some animals and bacteria) do to create hard shells and/or skeletons for structural rigidity and protection. And they form the base of aquatic food chains by converting carbon into organic matter.

- a little bit “animal.” Some diatoms are motile, able to move (glide) using a slit-like structure called a raphe, while others use internal oil/lipid vacuoles to control buoyancy for vertical movement/migration. In addition to creating energy through photosynthesis, some diatoms also “eat” to supplement their energy and nutrients by absorbing organic matter or engulfing prey. And while all diatoms reproduce asexually, they also undergo sexual reproduction to grow, creating larger cells.

- a little bit “mineral.” To make their unique biogenic silica frustules, diatoms must begin with the mineral silicon dioxide (SiO2), and add water. This amorphous (non-crystalline) hydrated silicon dioxide is the same material that forms opal!

And that is why diatoms are nicknamed “Jewels of the Sea” and “Living Opals!”

The very elegant, intricately patterned, transparent frustules defracts sunlight off all the microscopic silica spheres that went into the “construction” of their glass houses, just like they were formed from priceless jewels! Just like they are “Living Opals!”

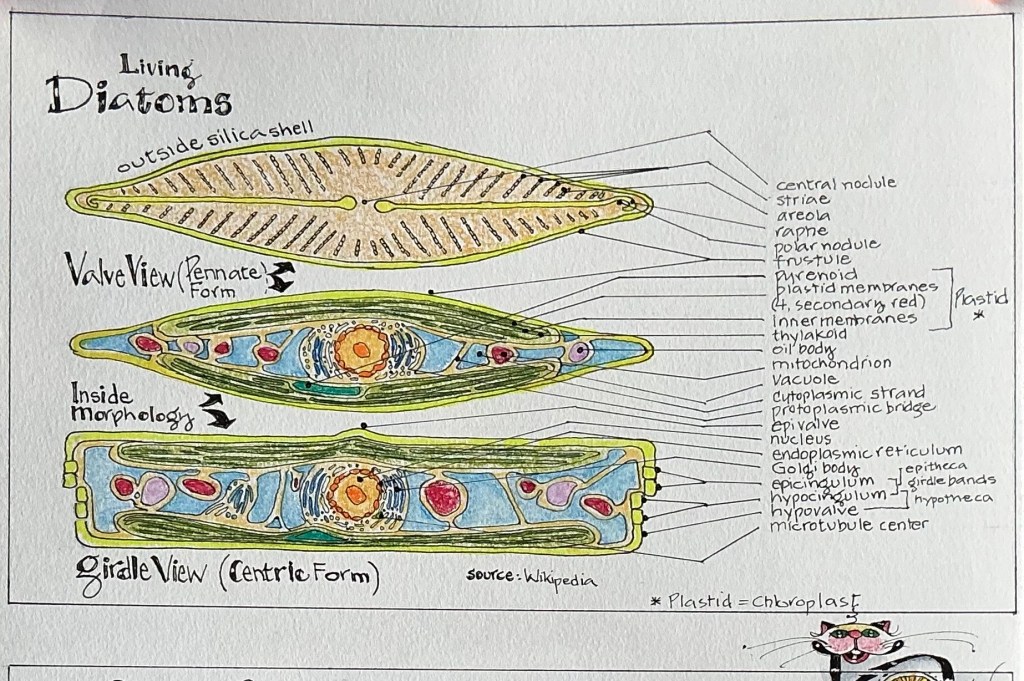

What Do Diatoms Look Like?

First Impressions

Diatoms look like shimmering gold gems in sunlight! That’s because they live in houses literally made of transparent glass! They’re the only organism known to have cell walls composed almost entirely of amorphous (hydrated non-crystalline) silica, the natural form of silicon dioxide (SiO2).

The glassy houses (frustules) of all diatoms are etched with intricate and beautifully-detailed patterns which aid in their identification. Each species of diatom creates frustules with unique designs, visible on both the upper (epitheca) and lower (hypotheca) surfaces (called valves) of their houses, This genetic characteristic makes one species readily distinguished from all others, by design patterns.

But these living frustules are not made of pure silica. They also have an organic layer. Their primary component is biogenic silica, a hydrated and polymerized silicic acid compound, similar to the gemstone opal. The biogenic silica, formed within the cell of the diatom in a specialized structure called the Silica Deposition Vesicle, is associated with several organic molecules such as proteins (silaffins and silacidins), long-chain polyamines, carbohydrates, and glycoproteins.

The biogenic silica gives the frustule its rigid, intricate, and highly porous structure. The organic matrix is crucial for controlling the precise nanoscale patterning and morphogenesis of the silica structure.

Upon Closer Inspection …..

….. you’d probably notice the two Valves (the epitheca and the hypotheca) of the frustule are connected by narrow bands. These silica structures are called the Girdle Bands (or the cingulum). The girdle bands are visible when viewing a diatoms in profile; the Girdle View.

….. you’d also notice the colors of the diatoms. Regardless of the design patterning of the frustules, all diatoms appear to be either yellow-brown to golden-brown, or sometimes greenish in color. There’s at least two reasons for this: 1) because of the photosynthetic pigments found in the Chloroplasts. The primary pigment fucoxanthin (a carotenoid), masks most of the greenish hues of both chlorophylls a & c (present in smaller amounts), giving diatoms their characteristic colors or hues; and 2) the transparency of the silica frustule allows these hues to show through the internal cell wall and the frustule.

….. you’d probably notice the many and varied shapes of diatoms, with two basic forms repeated over and over again; roundish (more or less) and oblong-ish. Yes, there are two basic forms (morphological groups) of diatoms, Centric and Pennate. Centric diatoms are usually round, have radial symmetry and are often planktonic, while pennate ones are elongated or boat-shaped, bilaterally symmetrical, and often benthic. Within both of these forms of diatoms exist a seemingly unlimited diversity of shapes, but you’d always find they are either centric or pennate. By the way, most diatoms fall within the pennate form.

….. you’d probably notice there are diatoms that appear to be stuck to a lot of other diatoms. These are the ones that live in Colonies, from the photic zone down to mid- and deep ocean levels, and may be attached to substrates (like corals or sediments) or free-floating in the water column. Colonies can be either centric or pennate with some forming colonies in chains or zigzags.

and perhaps lastly …..

….. you’d probably notice the pores on the frustules of all diatoms, and slits that are present some. Those tiny Pores allow for nutrient uptake and waste removal, while only some species have slits called Raphes, which allow the diatom limited movements.

How Big Are Diatoms?

Almost all known diatom species are microscopic. To comprehend just how tiny these single-celled organisms actually are, it’s helpful to compare them to another tiny and common creature; one that’s clearly visible with the naked eye; the Ant.

But first, a bit about Units of Measure at the Microscopic and Macroscopic Scales.

Things that are Microscopic, like pollen grains, bacteria, dust, filter ratings, and light wavelengths, are measured in microns or micrometers, two names for the same unit of length. “Micron” is the older, more common term, while “micrometer” is the official International System (SI) World’s standard name for this unit of measurement. Both names are abbreviated as “µm.”

One micrometer is equal to one-millionth of a meter (m) [also represented as 10-6 ] or one-thousandth of a millimeter (0.001 mm).

Things that are Macroscopic, such as people, reptiles, coins, trees, rocks, mountains, and everyday objects, exist at a scale much larger than a virus. Macroscopic things can be seen, measured and observed with the naked eye, without needing magnification, and are measured using the units of the SI system/the metric or base-10 system; or the U.S. Customary (non-base-10) system.

Today, the World’s standard or SI system is the most widely adopted for its coherence and simplicity. With that in mind, 1 mm = 1000 μm.

And one last thought regarding scale ….. a macroscopic view shows the whole thing (e.g., a piece of metal or a body of water), while a microscopic view reveals their atoms and molecules.

Now on to Diatoms vs Ants – Size Ranges

Because diatoms are almost entirely microscopic, they are measured in micrometers. These single-celled organisms range in size from a minimal dimension of less than 1 micrometer (μm) (0.001 mm or 0.00003937 inch) to a maximum of over 5,000 μm (5 mm or 0.2 inch). However, the typical size of most diatoms is generally 20 to 200

μm (0.02 to 0.2 mm or 0.0008 to 0.008 inch).

Because ants are entirely Macroscopic, they are measured in millimeters. Ants range in length from about 0.75 to over 52 mm (0.03 to 2 inches). But the length of most common species vary from 1.5 to 13 mm (0.06 to 0.5 inches).

Diatoms and Ants – Relative Comparison

Comparing the smallest ant (0.75 mm) to one of the largest diatoms (5 mm), the diatom is actually larger. However, the vast majority of diatoms are much smaller, with the smallest diatoms less than 1μm (0.001 mm), making them about 750 times smaller than the smallest Ant.

But if you compared a typical diatom (0.1 mm long) to a typical ant (7 mm long), an ant is 70 times longer than a diatom.

Basically, diatoms, which can appear as a speck of dust to the naked eye, exist on a Microscopic scale, while ants are Macroscopic and belong to an entirely different order of magnitude in size.

Where and How Do Diatoms Live?

Diatoms, found worldwide, are primarily Aquatic in nature and live their lives entirely in aquatic habitats. But many Terrestrial species have adapted to live very well in non-aquatic, moist habitats.

Aquatic Diatoms

Those species dependent on aquatic habitats exist in cold Rocky Mountain streams to hot thermal springs in Arkansas; from polluted pools to road side ditches; from ponds and lakes to streams, rivers, seas and the oceans. They thrive as free-floating (plankton or phytoplankton), attached, or bottom sediment-dwelling (benthic) organisms. For the most part, Aquatic Diatoms live in the sunlit upper layers (photic zone which goes 200 meters or 656 feet deep) of all waters, from oceans to freshwater lakes.

Terrestrial Diatoms

In moist or damp conditions, where moisture levels fluctuate or are unpredictable, there are diatom species that thrive in soils, sediments, or attached to mosses, tree trunks, rock faces and even brick walls. They exist happily in ephemeral marshes, bogs, fens and swamps. Other species make their home on the feathers of diving and wading birds, and waterfowl! Some even prefer the nooks and crannies of lichens to stay humid.

Adapting to Drought

Diatoms are very resilient. To survive drying out, they form resilient films on surfaces of temporary water bodies. Many secrete a protective, glue-like mucus (mucilage) that helps them cling to surfaces and retain moisture. To endure a lengthy drought when conditions become too dry, they transition into a low-energy resting stage, conserving resources until water returns, a process sometimes involving nitrate respiration. So, while diatoms need water to grow and reproduce, certain diatom species are masters of surviving desiccation in non-aquatic, moist environments.

When All Else Fails …..

Then there those diatoms, the endosymbionts, that live inside other small organisms, such as dinoflagellates and foraminifera. Both of these organisms are types of plankton, specifically phytoplanktons (microscopic, single-celled organisms, free-floating (drifting) and living in the photic zone of aquatic habitats). Although the majority foraminifera live as benthic (deep water) organisms.

Bottom line ….. Diatoms can thrive wherever there is sunlight, water, carbon dioxide, and the nutrients necessary for their growth and survival.

How Many Species of Diatoms Are There?

One of the largest groups of organisms on Earth, there are about 25,000 species of diatoms that have been documented, to date, each with their own unique shell (frustule). With new ones being discovered every year, scientists studying diatoms2 estimate there may be as many as 200,000 to 2 million species worldwide-wide.

Because diatoms exist in large numbers in most bodies of water throughout the world, if you collected just one liter of seawater, it can contain as many as ten million individual diatoms! This makes diatoms the most abundant type of phytoplankton, with the greatest numbers existing in cold oceans.

2 The study of diatoms, known as Phycology, is in a branch of botany concerned with seaweeds and other algae. A scientist studying Diatoms may be Protistologist, Diatom Paleontologist, Ecohydrologist, Environmental Botanist, Botanist, Diatomist, Paleolimnologist, an algal physiologist, a genomicist

or a Paleoceanographer.

It’s a Wrap!

DIATOMS!! JEWELS OF THE SEA//Part 2 – The Sequel

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

Hope you’ve enjoyed learning some fascinating facts from this introduction to living diatoms. Spread the joy and tell all your family and friends! They will be so impressed with your new-found knowledge of diatoms, and may even want to learn more about these Jewels of the Sea!

As I was compiling and organizing my notes for Part 2, many additional questions about diatoms and their compatriots popped into my mind. I’d love to know if you came up with some as well. If you share your questions with me, and I’ll dig around for answers. Also, if you have any questions about or clarifications needed regarding the information in this Part 2 introduction, I’d welcome them via message or comment on the post.

Meanwhile, here’s a teaser from the upcoming Part 3 in my Diatom Series. Things I’ve wondered about while researching diatoms:

Do diatoms breathe? Eat? Reproduce? How long do they live? What good are diatoms? What do they eat and are they food? What’s their relationship with the global carbon cycle? Are diatoms all good and wonderful? Do they have a bad side?

…………………………………. ………………………………………………………….

If you feel yourself becoming a “Diatomic Geek,” you may find interest in browsing the following Glossary of terms. If a term used within the text of my post is in bold font and italicized, it is (or will be) in the Glossary. (Fair warning: my Glossary continues to be a work-in-progress. Look for an updated version in Part 3 of this series on diatoms.)

Glossary

Archaea(ns) – single-celled microorganisms similar in structure to bacteria, but evolutionarily distinct from bacteria and Eukaryotes. They are obligate anaerobes living in low oxygen environments (e.g., water, soil), and form a commensal (symbiotic) relationship in ruminant and human intestines. When Archaea is the commensal, it benefits from the relationship with the host without causing harm, or may provide certain benefits to the host (i.e. the human intestines).

Archaeans may be the only organisms that live in some of the most extreme environments on the planet; habitats hostile to all other life forms. Some live near thermal rift vents in the deep sea at temperatures well over 100 degrees Centigrade. Others live in hot springs, or in extremely alkaline or acidic waters. They thrive inside the digestive tracts of cows, termites, and marine life where they produce methane. They live in the anoxic muds of marshes and at the bottom of the ocean, and even thrive in petroleum deposits deep underground. They survive the dessicating effects of extremely saline waters.

However, archaeans are not restricted to extreme environments; they are also found, in abundance, in the plankton of the open sea.

Autotroph (aka Producers) – an organism that produces its own food using external energy sources like sunlight (through photosynthesis) or chemical compounds (through chemosynthesis).

Biogenic silica (bSi) – is amorphous, opal-like hydrated silica (SiO2 · nH2O) produced by living organisms, forming structures like diatom shells (frustules), sponge spicules, and plant phytoliths, playing roles in structural support and defense against stress. It’s a key component in marine and terrestrial ecosystems, with significant deposits like diatomaceous earth (DE) from fossilized diatoms.

Biosilicification – the biological process where living organisms take up soluble inorganic silicon (silicic acid, Si(OH)4) from their environment and convert it into solid, polymerized, insoluble silica (SiO2) to form hard structures like shells, skeletons, or cell walls, crucial for diatoms, sponges, and plants, and even occurring in some bacteria and mammals. This process is a form of biomineralization, where organic molecules are used to control the precise formation of these silica materials.

How it works – 1) the organism must uptake (absorb) silicic acid; 2) then polymerization takes place, where inside or outside the cell, the silicic acid condenses, forming chains of silica with the removal of water; and 3) specialized proteins and other macromolecules guide (control) this process, creating complex, often intricate silica structures (biogenic silica) like those found in diatom frustules.

Carbon fixation – diatoms “fix” carbon by removing inorganic carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere and converting it into organic carbon in the form of sugar (glucose). During this process, oxygen (O2) is released back into the environment, producing 20-30% of the air we breathe.

Catalog of Life – the 1998 Kingdoms of Life were replaced in 2015 with today’s adopted Catalog of Life: At the top most tier or classification rank are two Super Kingdoms, Prokaryota and Eukaryota. The next descending rank the Kingdoms, of which there are seven, (under Prokaryota are two Kingdoms: Bacteria and Archaea); under Eukaryota are five Kingdoms: Protozoa, Chromista, Plantae, Fungi, Animalia).

Centric – a diatom withValves (cell walls) that are radially symmetrical.

Chloroplast – also called a Plastid, a chloroplast is photosynthetic organelle that absorbs light molecules (sun’s energy) through chlorophyll a & c, turning it into chemical energy by way of photosynthesis.

Diatom – a microalgae that forms a significant part of the food chain in moist soils and aquatic (marine and freshwater) ecosystems. They form long-chain fatty acids that are an important source of energy-rich molecules and provide a critical food source for the entire food chain, from tiny zooplankton to fish to whales. So it can be said that diatoms feed oceans, lakes, streams, rivers and associated wetlands and riparian areas.

Dinoflagellates – single-celled microscopic organisms with two whip-like tails (flagella), making them motile. They are found drifting in large numbers in marine plankton, specifically phytoplankton; also found in fresh water. Some produce toxins that can accumulate in shellfish that, when eaten, results in poisoning. Dinoflagellates form crucial part of the ocean’s food web, producing a significant portion of the world’s oxygen, dinoflagellates are known for causing red tides and bioluminescence.

Endosymbiont – an organism that lives inside another organism (its host), forming a symbiotic relationship, usually where both (mutualism), but sometimes one benefits at the other’s expense.

Ephemeral – something that lasts for a very short time.

Eukaryotes – organisms characterized by complex cells; a membrane-bound nucleus that contains DNA, and other membrane-bound organelles like mitochondria. Eukaryotes can be unicellular or multicellular, fall within the Super Kingdom Eukaryota that includes animals, plants, fungi, and protists (such as algae [like diatoms and seaweed], amoebas, slime molds) The Eukaryotes represent a major group of life on Earth.

Flagella – an appendage that provides motility.

Foraminifera (forams) – a single-celled animal with a perforated chalky, calcium carbonate shell, through which extend slender protrusions of protoplasm. Most forams are marine species – some float in the water column in the photic zone (planktonic); most live on the sea floor (benthic). When benthic forams die, their shells form thick ocean-floor sediments.

Frustule – the external, silica cell wall of a diatom. The frustule is composed of two valves and the girdle bands. The upper valve, or epitheca, is slightly larger than the lower valve, or hypotheca. The epitheca overlaps the hypotheca similar to the halves of a pill box or a Petri dish.

In diatoms, frustules are not made of pure silica. They also have an organic layer. Their primary component is referred to as biogenic silica. (Read more about the make up of biogenic silica under the definition for “Silica” below.

Girdle bands – the bands (aka cingulum) that connect the two Valves (epitheca and hypotheca). The girdle bands are visible when viewing a diatom in profile. (Girdle = Copulae)

Girdle view – the profile view of a diatom; view appears rectangular in both Centric and Pennate diatoms.

Kingdoms of Life – in 1969, the five major groups of life – aka Kingdoms of Life – were classified as: 1) Fungi, 2) Animalia, 3) Plantae, 4) Protista (the water molds, brown algae and diatoms); and 5) Monera (the bacteria and archaea). In 1990, there were three Domains: 1) Eucarya (including diatoms), 2) Bacteria, and 3) Archaea. Another change was made in 1998, now with two Empires (Prokaryota and Eukaryota) that ranked over six Kingdoms (Prokaryota ranked over one Kingdom, Bacteria; Eukaryota ranked over five Kingdoms: 1) Protozoa, 2) Chromista, 3) Plantae, 4) Fungi, and 5) Animalia.)

Pennate – a diatoms with Valves (cell walls) that are bilaterally symmetrical.

Plastid – also called a Chloroplast, a plastid is photosynthetic organelle that absorbs light molecules (sun’s energy) through chlorophyll a & c, turning it into chemical energy by way of photosynthesis.

Photosynthesis – the chemical process where plants and some other organisms with chlorophyll, through the use sunlight, combine inorganic carbon dioxide with water to form carbohydrates (sugars), releasing oxygen as a byproduct.

Prokaryotes – a microscopic single-celled organism without organized internal structures; that has neither a distinct nucleus with a membrane nor other specialized organelles. Prokaryotes include the bacteria and cyanobacteria.

Protists – a diverse group of complex Eukaryotes (organisims with a nucleus and organelles) that don’t fit into the categories of animals, plants or fungi. Protists are diverse life forms, mostly single-celled but sometimes colonial or simple multicellular forms, found in aquatic environments. They are incredibly varied, acting like animals (amoebas), plants (algae), or fungi (slime molds), and playing vital roles in ecosystems as producers and decomposers. The Protists are split into two Kingdoms, Protozoa and Chromista, under under the Super Kingdom Eukaryota. Diatoms fall under the Kingdom Chromista as described in the Catalog of Life.

Protoplast – refers to the living cell contents of diatoms, including the cytoplasm, nucleus, and other organelles, and is contained inside of the rigid silica cell wall. The protoplast is the part of the diatom that grows and divides. During division the protoplast duplicates, splitting into two complete daughter cells. But unlike typical plant cells, before the daughter cells can separate into two complete diatoms, a new silica valve is formed for each daughter protoplast to pair with one of the parent’s valves. Now the complete daughter cells separate, each with its own new species’-unique external silica shell (the frustule).

Raphe – a slit or groove opening in the silica cell wall (frustule) of a pennate diatom to allow it gliding motility and attachment to a substrate by secreting sticky mucilage, allowing these diatoms to move along surfaces and find nutrients.

Red tides – more appropriately described as Harmful algal blooms, or HABs, occur when colonies of algae—plant-like organisms, such as dinoflagellates, that live in the sea and freshwater—grow out of control while producing toxic or harmful effects (death, in some cases) on people, fish, shellfish, marine mammals, and birds. Eating organisms affected by the toxins, like fish and shellfish, make them dangerous to eat. The toxins may also make the surrounding air difficult to breathe. One of the best known HABs in the U.S. occurs nearly every summer along Florida’s Gulf Coast. This bloom, like many HABs, is caused by microscopic algae that produce toxins that kill fish and make shellfish dangerous to eat. As the name suggests, the bloom of algae often turns the water red.

Silica – a mineral, specifically a compound of silicon and oxygen, called silicon dioxide (SiO₂), is one of the most abundant minerals in the Earth’s crust. Silica is most commonly found as quartz, but also in other solid forms like cristobalite, tridymite, and opal.

In diatoms, the living frustules are not made of pure silica. They also have an organic layer. Their primary component is referred to as biogenic silica, a hydrated and polymerized silicic acid compound, similar to the gemstone opal. The biogenic silica, formed within the cell of the diatom in a specialized structure called the Silica Deposition Vesicle, is associated with several organic molecules such as proteins (silaffins and silacidins), long-chain polyamines, carbohydrates, and glycoproteins.

Silica Deposition Vesicle – a specialized internal structure of a diatom, where its silica shell (frustule) is built before being exported.

Stramenopiles – a phylum (also referred to as a clade), synonymous with the phylum Gyrista

within the Protista Kingdom. The Stramenopiles (aka Heterokonts) include Water Molds, Brown Algae (Sargassum species, Fucus species, and Kelps), and Diatoms (Centric and Pennate).

Valves – the cell walls of diatoms are made up of two Valves; top (epitheca) and bottom (hypotheca). The top Valve is slightly larger so it overlaps the bottom Valve, like a pill box or Petri dish.

Valve view – the view of a diatoms when looking face-on at one of the two Valves.