Many Hearty Thanks, Sharing Creative Ideas, Answering the ‘Kat’ Kwestion

April 1, 2025

Completing my 15th sketchbook, and beginning the next one is always cause for celebration! To do so, Kat and I thought it would be especially fitting to shout-from-the-treetops enthusiastically, THANK YOU! Thank you all, my loyal subscribers, for coming along on my interesting, hopefully educational, sometimes crazy, always curious nature journaling adventure.

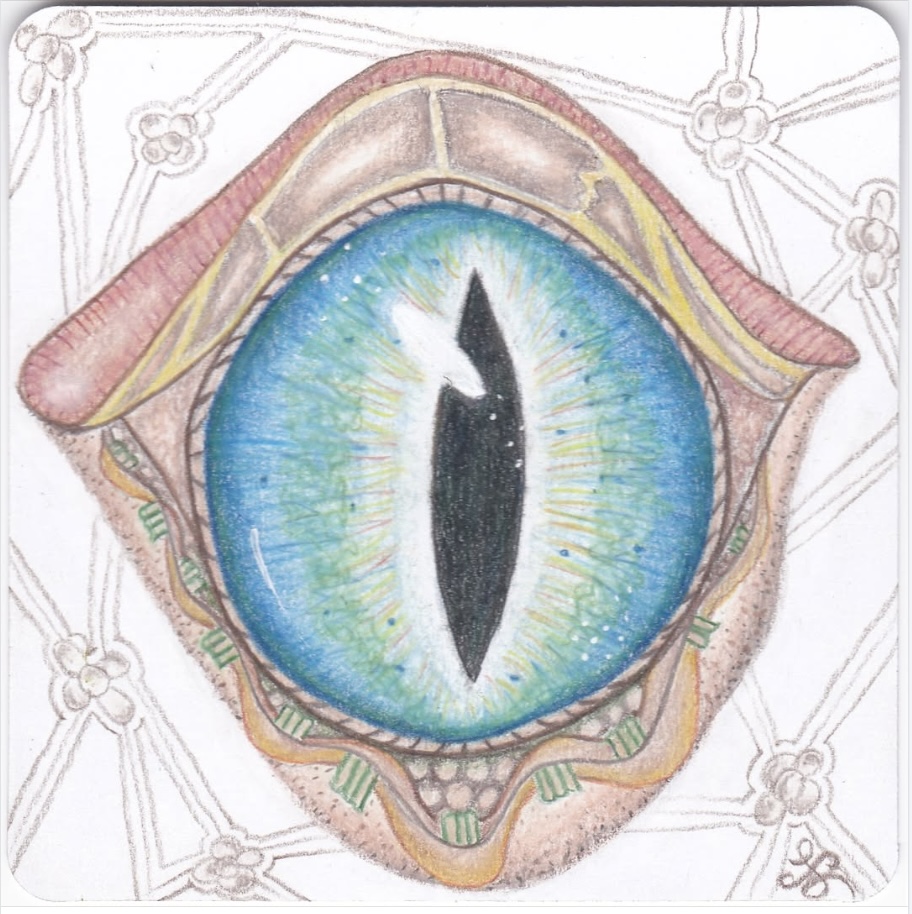

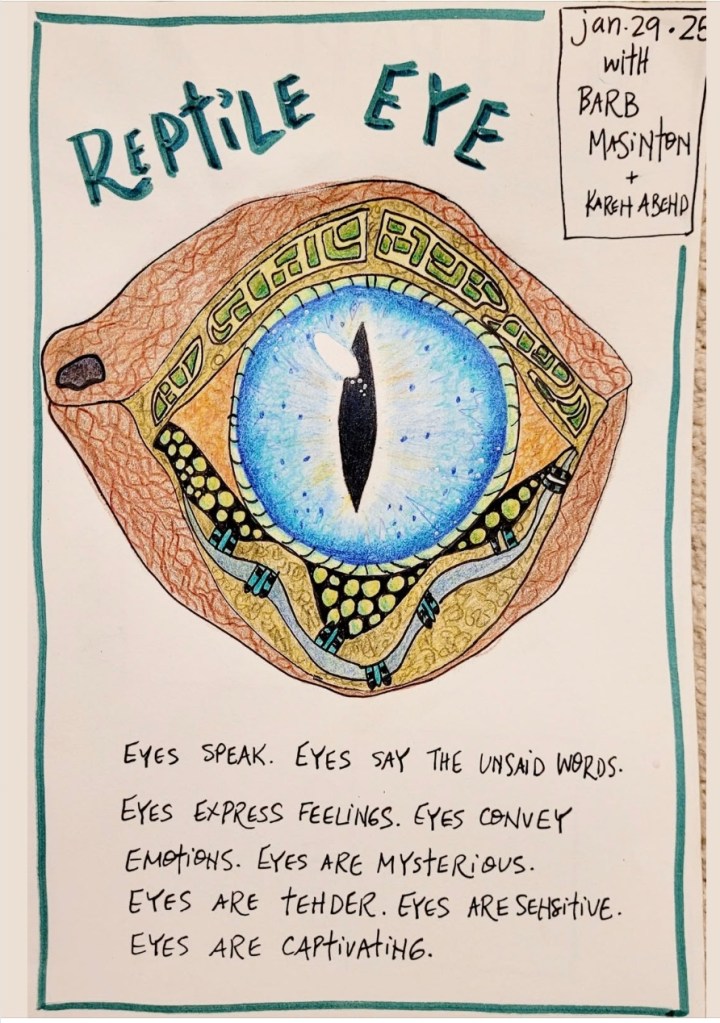

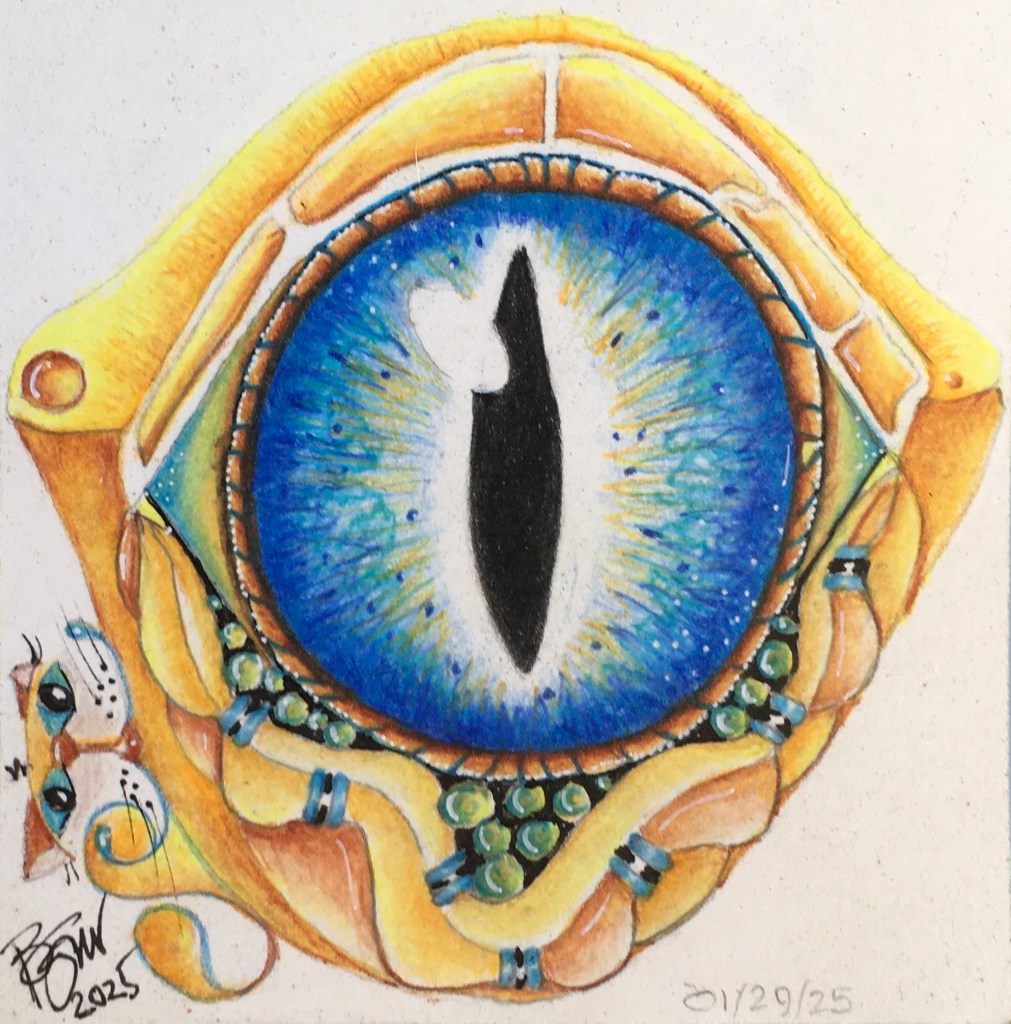

My recent webinar class, “Create a Colorful Reptile Eye1,” sponsored by Host Karen Abend (of Sketchbook Revival fame), generated many new subscribers to my web page and blog, “A Curious Nature.” Wow! And Thanks so much. A special thanks to those who attended the live and/or recorded class. I loved seeing so many colorful lizard eyes (a sampling below). They were incredible!

Sharing the Wonder of Nature

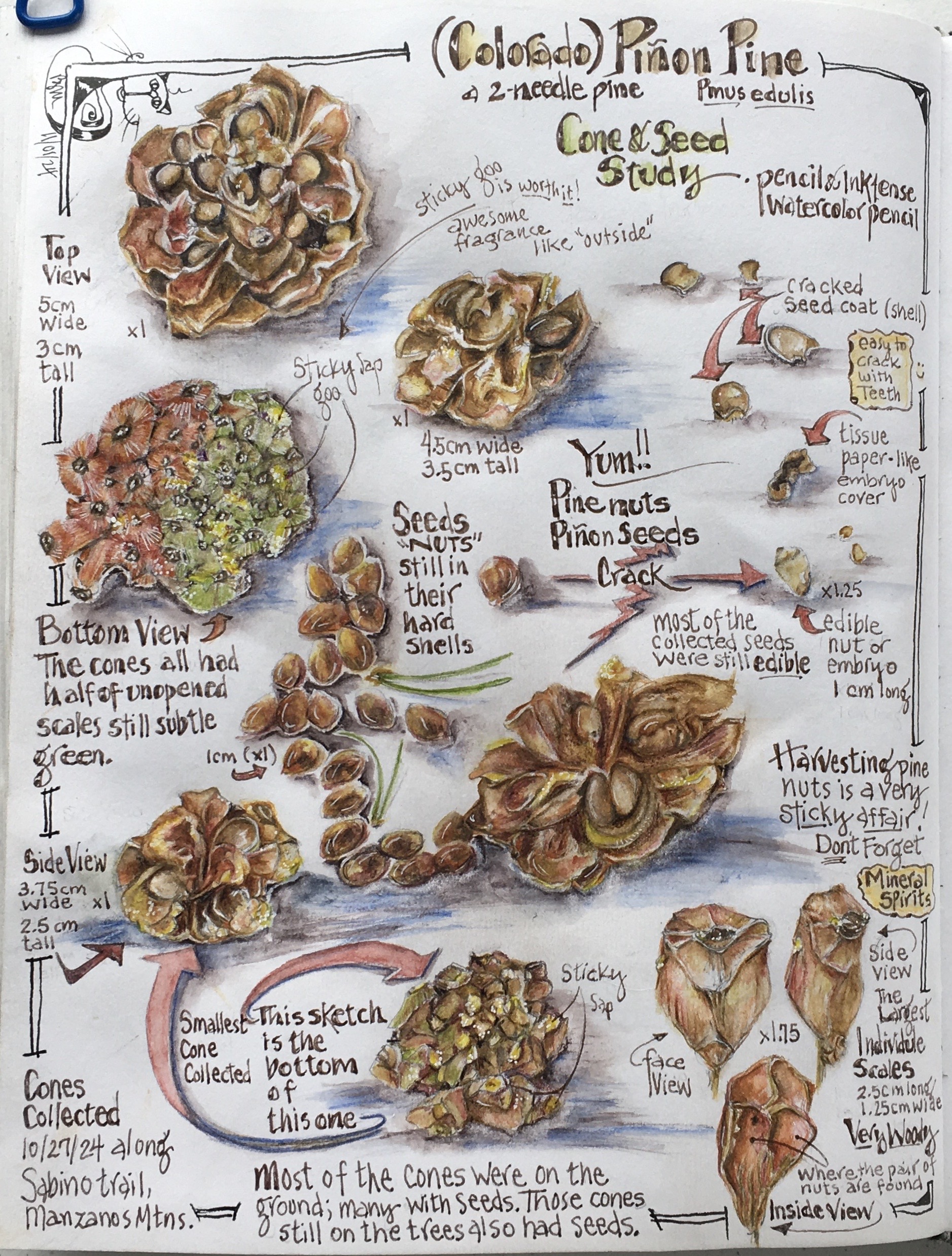

With all the past and current activity on my blog, I feel so fortunate and very encouraged to carry on. Even though new postings have been random lately, there’s lots of works-in-progress soon to be shared. Meanwhile, comments including what you like about my posts and what you’d like to see more of, are always appreciated. What inspired you to subscribe to this blog? If it’s just enjoy, that’s perfect! Or maybe you’d like tips to develop a regular or even a daily creative practice, how can I be more encouraging? I’d love to know if you are an active nature journaler or tangler, or express yourself by creating art in other ways, such as through music, poetry, or storytelling. Send me your ideas by commenting on this or any future posts. I’ve created my webpage and blog because of my insatiable curiosity about the natural world. It’s extraordinarily fun to go beyond learning what the names of flowers, animals, rocks, and clouds are. The excitement of wondering and discovering answers for all the why’s, who’s, when’s, and how’s is so rewarding. Sharing is my joy!

Explaining Kat

Thinking new subscribers may be puzzled by my constantly mentioning Flambé or Kat or both, now might be a good time for explanation and background (and perhaps provide a refresher for those who’ve been following along from day 1 of my blog):

In 2014, a young stray calico cat showed up one day on our doorstep when we (Roy and I) lived in Oriental, North Carolina (U.S.A.). This little wild miss seemed to magically appear from our backyard woods, perhaps in search of a meal or a friend. She sat and meowed for a few minutes, but when we opened the door, she ran away. Efforts to get close to her when she returned several times during the week were futile. Then one day she vanished and never returned. Not knowing what may have happened to this pretty kitty, Roy thought a nice remembrance of her visit would be to add a small cat sketch to my next drawing. A dandy idea!“But only one drawing,” I thought? It was at that moment that Flambé appeared on my creative doorstep, and has never left!

Flambé, aka Kat, is always smiling, popping in and out of all my art, regardless if the piece is imaginatively & whimsically tangled or a serious nature study. Along with forming the best part of my signature “chop,” she’s the heroine of some pretty wild and crazy tangled misadventures, sometimes pushing Kat’s 9-lives threshold to satisfy her insatiably curious nature (and appetite). Flambé adores being noticed, whether she hides inside the story, or shows up front and center. She makes everything creative more fun. Flambé may be just “Kat,” but she’s my inspiration for and reminder about the value of komic relief, and makes the perfect konstant kompanion!

Whew! That’s all for now. Hopefully your questions about this blog, inspiration and Kat have been answered. If you’re craving to learn answers to other related topics, let me know. Meanwhile, Flambé and I wish you an exciting and creative remainder of the year ….. have times full of happiness, creativity, and memorable adventures, but most of all laughter and fun!

Hope to hear from you soon, and as always, thanks for stopping by!

Meow!

1Unfortunately, the class or recording are no longer available for viewing. But I may have another live demo class some day in the future. If so, you can be sure the announcement will show up on my blog.