National Diatomaceous Earth Day

Part 3 – The Sequel

February 9, 2026

While my quest to learn the facts and fancies of diatoms and their curious lifestyles hasn’t wavered since Part 1 – Diatomaceous Earth posted last fall, and continued in earnest through Part 2 – Diatoms!! Jewels of the Sea posted in early January, understanding, compiling and following through with the information for Part 3 – Diatoms!! Microscopic Lifestyles has been the most challenging, especially related to their reproduction. The asexual and sexual phases of a diatoms’ life is complex and unique; full of “ah-ha” moments. No sooner had I thought all the pieces and parts had fallen into place and made sense, then another answer to an elusive loose end revealed a certain puzzle piece no longer fit! Rewrites and intense edits caused many corrections to my illustrations as well, and kept leading to additional diagrams. But loving a challenge, I worked slowly and carefully, and never gave up. Can’t guarantee everything is absolutely 100% correct, but I’m confident it’s darn close!

By the way, if you missed parts 1 and/or 2, click on the links above to catch up!

With that explanation and bit of a disclaimer, I give you …..

Part 3 – Diatoms!! Microscopic Lifestyles

In this post, I’ll discuss and/or answer the following questions:

Do Diatoms Breathe? Do Diatoms Eat?

How do Diatoms Reproduce? How Long do Diatoms Live?

As in Part 2, if something in the narrative is bold and italicized, it’s a word or phrase further defined in the updated version of the Glossary

Do Diatoms Breathe?

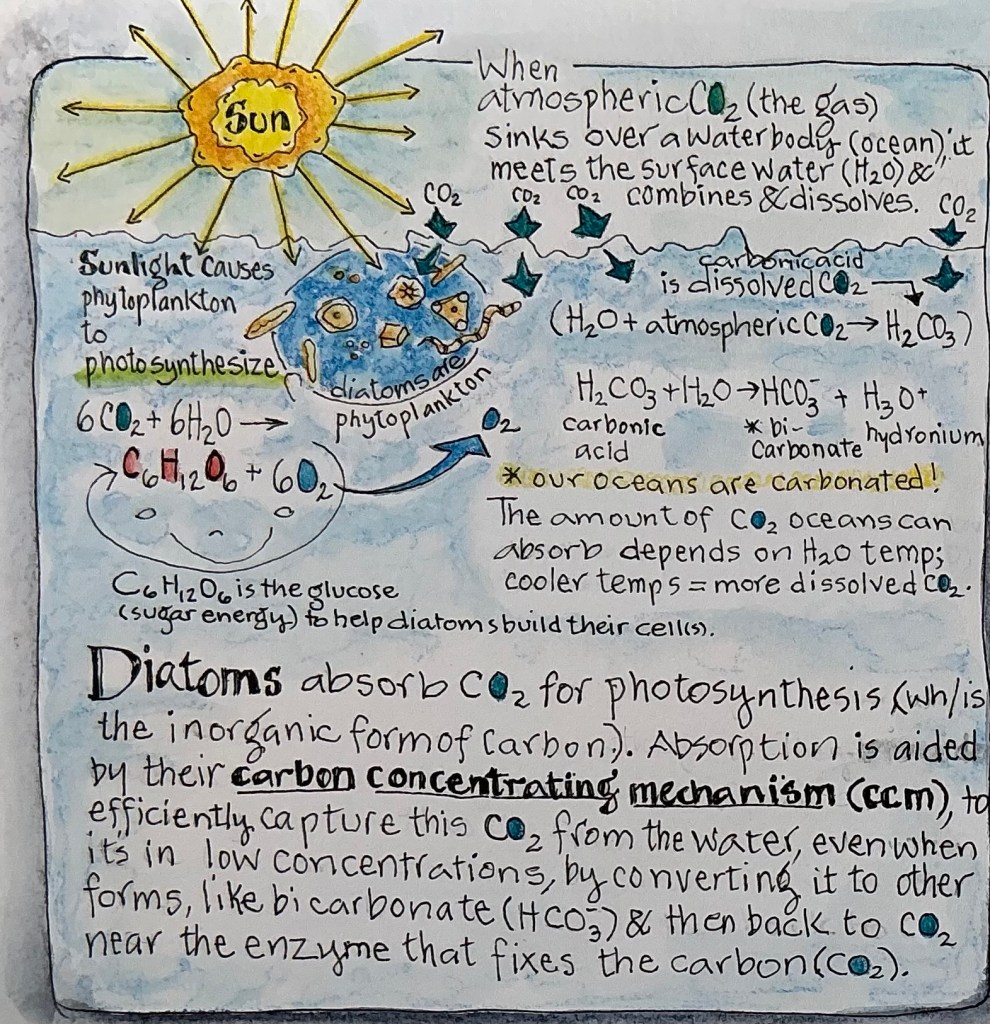

Yes, diatoms breathe! These single-celled microscopic organisms take atmospheric inorganic carbon dioxide (CO2) that’s been dissolved in water, and “breathe it in” by absorbing it through their silica shell (frustule) into their cell. Once inside, the CO2 is transported into the chloroplast where it is converted into organic carbon (glucose/sugar) through photosynthesis. One of the byproducts of photosynthesis is oxygen (O2), which is “exhaled” (released) into the water where it’s available for all kinds of aquatic organisms. The O2 that escapes inhalation eventually ends up in the atmosphere. Scientists estimate 20 to 50% of the O2 we breathe is produced by diatoms.1 At a minimum, that equates to every 5th breath we breathe! Diatoms release so much O2 that it exceeds that produced by all the world’s rainforests!

1Here’s one of more than a dozen scientific references I found with estimates on the amount of O2 released by diatoms. https://www.mpi-bremen.de/en/Algae-in-darkness-Survival-strategy-unraveled.

Do Diatoms Eat?

Yes, diatoms eat! In the way similar to plants, they produce their own food through photosynthesis. Using energy from sunlight, diatoms combine water (H2O) with inorganic carbon dioxide (CO2) to make organic carbon in the form of glucose/sugar (C6H12O6). Glucose provides the carbon and energy source needed for diatoms’ growth and survival. It’s used to produce valuable compounds like lipids, fuel cellular processes through glycolysis, for respiration (especially in low light), and when supplementing photosynthesis. Glucose allows diatoms to achieve a higher biomass and to produce high-value products like Omega 3s (more about that in Part 4).

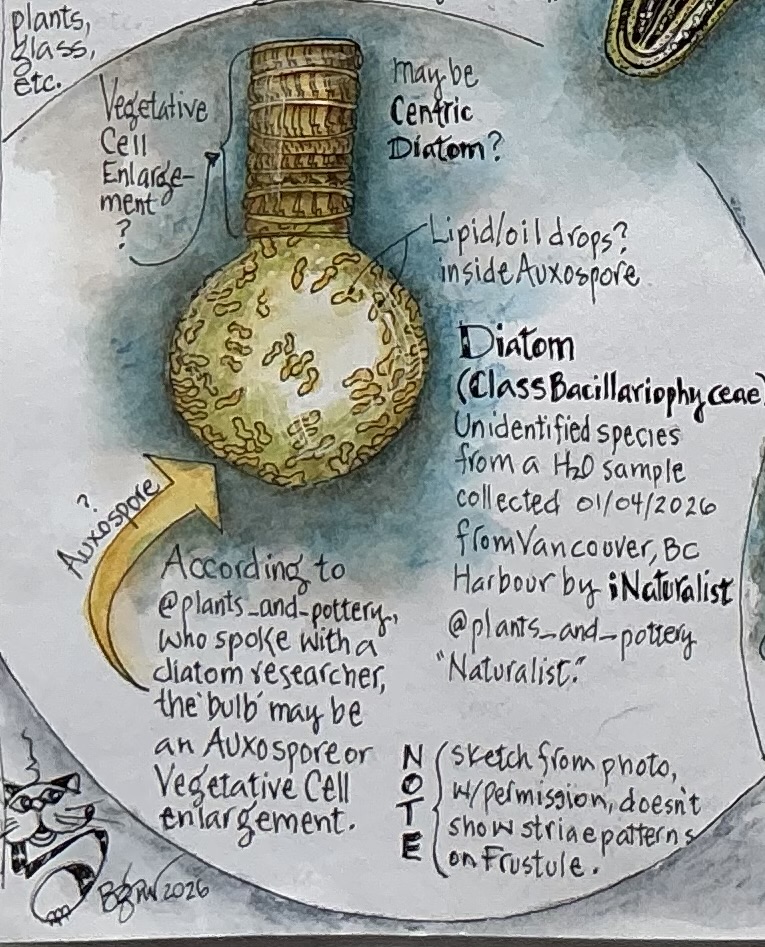

The glucose not required for immediate cell functions, goes into long-term storage as lipids (oil droplets) rather than carbohydrates like plants. Should diatoms drift into nutrient-deficient water, they can use the energy-packed lipids to perform critical cell functions. And lipids also provide them the buoyancy needed to stay in the upper sunlit levels (photic zone) of a water body.

But their appetites don’t stop there. Diatoms must also “eat” nitrate and phosphate, often from decaying organic matter. By absorbing these critical macronutrients, along with the mineral silicon dioxide (SiO2) from the water, diatoms convert them into organic forms crucial for building cells, cell membranes, growth, making proteins, DNA and RNA, reproduction, and structure when building their silica shells (frustules).

Now there are many species of diatoms (the benthic species) that live deep in the ocean or lakes, sometimes buried in sediments, well below the photic zone. At these depths the sun’s light can’t penetrate. How these diatoms are able to survive involves nitrate. They accumulate large amounts of this macronutrient inside their cells that can be used for respiration when light and other macronutrients are scarce, allowing them to thrive and reproduce in deep and dark waters.

Too much of a good thing? Diatom Blooms

While on the topic of diatom cuisine, it’s a good time to mention their appetite. Every year around the world diatom populations increase exponentially, seemingly overnight. As annual events, these Diatom “Blooms” peak during Spring, coinciding with an overabundance of nutrients and minerals (specifically nitrogen, phosphorus, and silica) and favorable environmental conditions (like high sunlight, warm water, and low water flow). Under these conditions, diatoms can double their numbers every 24 hours and continue that growth rate for up to 6 weeks. Because diatoms are considered “first colonizer” algae, they thrive in disrupted or newly established ecosystems, not only in the Spring, but they’re “blooming” earlier and more frequently year-round due to climate-induced triggers (more about ‘triggers’ in Part 4).

Have you witnessed a Diatom “Bloom?”

You have, if you have or have ever had an aquarium! And you know the few weeks following a new set-up can turn into a horror show. All your carefully chosen and arranged features like rocks/pebbles, gravel/sand, the plants, soil and driftwood, and those tiny plastic houses, all the way to the filter, water heater and even the tank’s glass became densely covered in a golden-brownish feathery slime! These coatings of goo, all the ‘norm’ during the initial cycling phase, are caused by a diatom “bloom” (aka brown algae “bloom”). Obviously you’ve unwittingly provided the now resident diatoms (having arrived in the tank when you filled it) the ideal combination of conditions …. an abundance of silica from the rocks to sand, the glass tank walls made of silica, and the silicone-formed plastics derived from silica, along with the nitrogen (nitrates) and phosphorus (phosphates) from all the organic features like live plants and speciality soils. All abundant and new sources of food for always hungry diatoms which happily consume and reproduce with wild abandon. Voilà! A Diatom Bloom!

If the only place you’ve ever gazed into an aquarium was at your dentist’s office, you may still have witnessed a diatom “bloom.” Ever try to tip-toe across a lovely mountain stream without getting soaked? You probably chose a likely crossing where the rocks in the water looked perfectly spaced with only a hint of wetness. Off you go with your confidence soaring, when halfway there your right boot makes contact with something brownish covering the top of the rock. Before your left foot makes its move, down you fall into the stream. As you look at that offending rock you have now fully grasped in one hand (very relieved it wasn’t that brown “thing”), you experienced a cold and slimy feeling that somehow resembles rotting lettuce, but not quite. And while you’re thoroughly soaking your jeans, you glance around and notice more rocks covered with this brown stuff. This may have been your first diatom “bloom” encounter!

Diatom “blooms” will be revisited below and in Part 4 of my Diatom series, where I’ll include a detailed description of the key factors triggering their rapid growth, examples of some recent occurrences, and the effects their huge populations have on nutrient cycling, aquatic organisms and human health.

How do Diatoms Reproduce?

Diatoms are very versed in two (wow! TWO!) ways of reproduction; asexual, biologically called Mitosis; and sexual, otherwise known as Meiosis. To understand the reproduction process of diatoms, one would need a few lifetimes. It’s taken me months of study to try and make sense of all the basic steps. And just when everything seemed to click, those microscopic organisms threw me a cargo ship full of curveballs! My following narrative and accompanying illustrations are a “summary” of what I think I now know about the unique, fascinating and involved steps diatoms take to conduct the most common forms of asexual and sexual reproduction. It makes perfect sense to me; my wish is that it makes sense to you too!

Asexual Reproduction (Mitosis) …..

……… also called vegetative cell division or binary fission, is the predominant method of reproduction in diatoms where a single diatom (parent cell) divides into two genetically identical daughter cells. Like many other eukaryotes, diatoms are diploid (2n) during the vegetative stage of their life cycle, dividing by mitosis and cytokinesis.

The reproduction process begins when the nucleus migrates to a specific location in the cell; usually somewhere along the bisecting valvar plane (the exact site is species specific). The nucleus then undergoes mitosis, with the chromosomes condensing and forming a ring around a cylindrical core of microtubules. Next, the chromosomes separate and move to opposite sides of the cell. More typical of animals than plants, the parent cell initiates cytokinesis by progressively closing a cleavage furrow, pinching the diatom’s cytoplasm in two. After the daughter cells receive half a valve (theca) from the parent’s frustule (that becomes their epitheca), the silica deposition vesicle is used to synthesize and export their second, smaller valve (the hypotheca) to fit inside the epitheca. After each newly synthesized hypotheca adjoins the half donated by the parent, the daughter cells grow then separate from one another, leaving behind what’s left of the parent cell to eventually become part of the marine snow.

Supplemental Note: The daughter cell that inherits the larger parent valve (epitheca) stays close to the original size of the parent, but the one that gets the smaller parent valve (hypotheca) always ends up notably smaller. The downside of mitosis is the process repeats over and over again, causing diatoms to shrink in size over generations. When their cells become too small, they must, somehow, be restored to their maximum size. Sexual reproduction (meiosis) is the most common of four known methods2 used by diatoms to accomplish this task, and prevent a species from extinction.

Takeaway

Every time a diatom divides via asexual reproduction (mitosis), the size of its silica cell wall (frustule) is reduced … and once the cell reaches a critical threshold, it switches to sexual reproduction (meiosis). What “an elegant method for a unicellular organism to escape death.”

Sexual Reproduction (Meiosis) …..

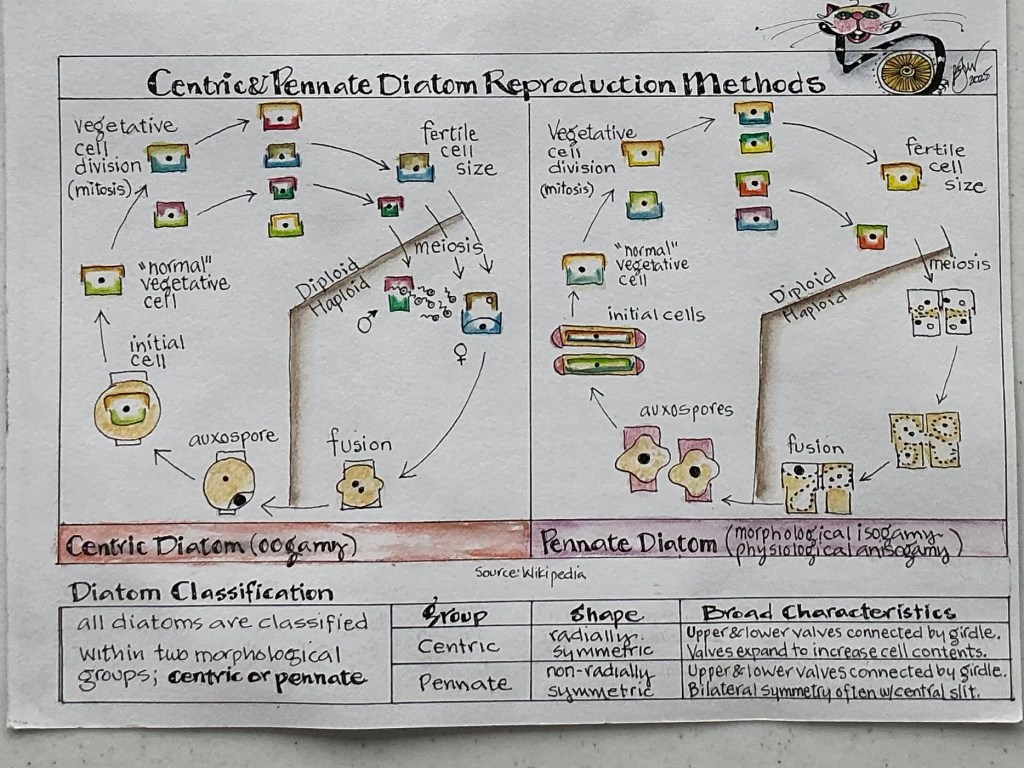

….. is triggered when the size of a diatom’s cell becomes less than critical threshold (usually smaller than half the original (maximum) size for most species). And to complicate things even more, sexual reproduction in centric diatoms is different than what happens in pennate diatoms. Of course!

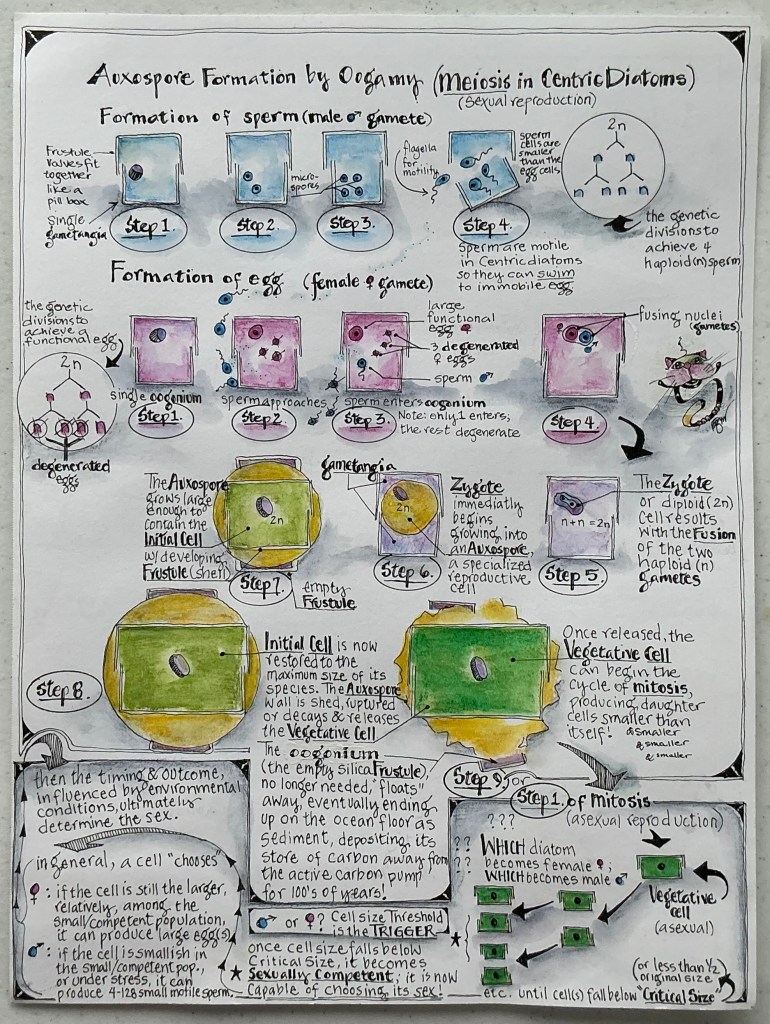

Centric Diatoms undergo oogamous meiosis. But first there’s a crucial decision to be made by diatoms; which cell becomes the male and which the female?3 Once decided, the designated male cell (the male gametangia) undergoes a series of divisions to form usually four (up to 128) sperm mother cells (microspores) which undergo meiosis to form four small haploid (n) flagellated (motile) sperm. Next, the female cell (oogonium) produces one to four large non-motile haploid (n) eggs; one remains functional and three degenerate. Then the protoplast of the oogonium allows only one of the four sperm to enter the cell by means of its species-specific mechanism; the unlucky three sperm degenerate. Fertilization (fusion of the sperm and egg) follows, resulting in the formation of a diploid (2n) zygote. The zygote then enlarges by water uptake to form a typically spherical-shaped, specialized reproductive cell (auxospore). As the auxospore enlarges it outgrows the now empty oogonium, pulling apart the two valves. Growth continues until the auxospore is large enough to contain the initial cell with its developing frustule. When the initial cell is restored to the maximum size of its species, the auxospore wall is either shed, raptured or decays, the oogonium valves drift to the seabed, and the new vegetative cell is released to begin asexual reproduction (mitosis), producing daughter cells smaller than itself. Whew! And that’s how centric diatoms undergo sexual reproduction!

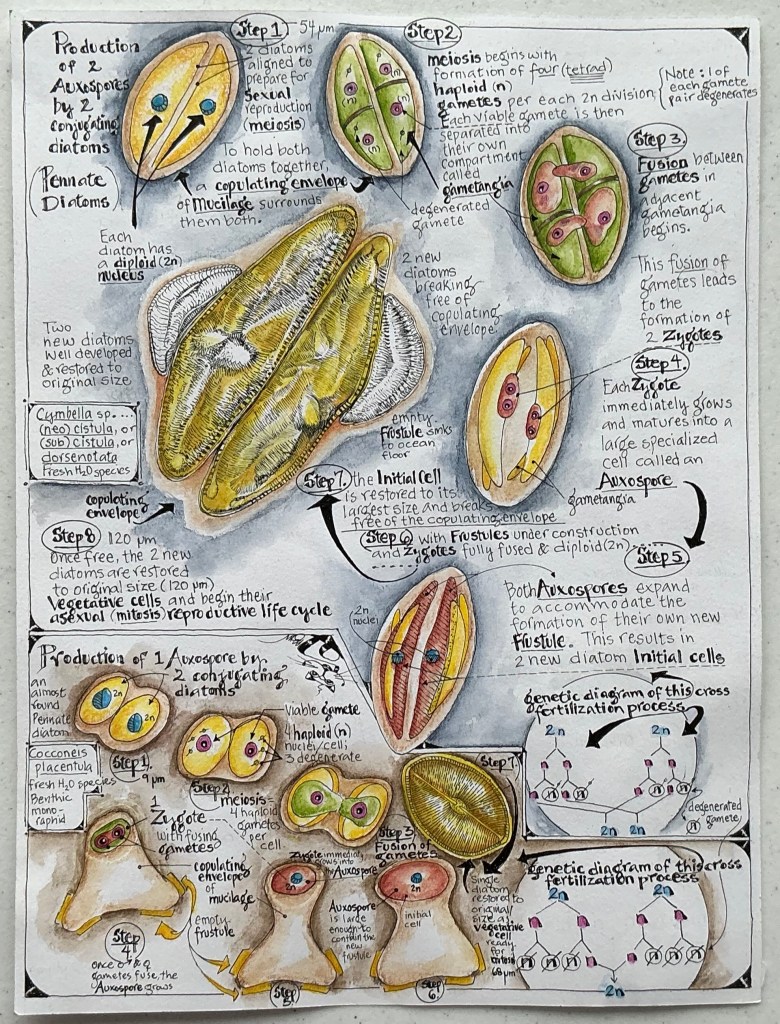

Pennate Diatoms undergo isogamous meiosis. For most pennate diatoms meiosis doesn’t involve motile sperm. In fact, there’s no “assignment” of sex to the two gametes that undergo fusion in isogamous meiosis. Before meiosis can begin, two diatoms align themselves side-by-side, pairing up their gametangial cells. Then to fuse them together, each diatom secretes enough mucilage to form a sheath (copulating envelope), completely surrounding their frustules and to embed their gametangia during copulation. Now meiosis begins.

First the diploid (2n) nucleus in each diatom divides and divides again to produce four haploid (n) gametes followed by the degeneration of one of each pair. The four remaining viable gametes are then separated into their own compartments (gametangia); two per diatom. They then become amoeboid in shape. To undergo conjugation, each of the two pair of amoeboid-shaped gametes must find a partner by moving, via pseudopodium-like appendages, and then penetrating their gametangial cells and the frustule wall adjacent to their paired diatom (a step enabled by the mucilage production that embedded the copulating cells) to fuse and form diploid (2n) zygotes. The two zygotes immediately begin forming one or two auxospores (depending on the species). As in centric diatoms, auxospore growth continues until they are large enough to accommodate the developing initial cells and their new frustules. When the initial cells have reached their maximum size, both are released from their auxospores and copulating envelope as vegetative cells ready to begin asexual reproduction (mitosis).

2 In addition to conventional sexual reproduction (meiosis), diatoms can restore their maximum cell size through other methods: vegetative cell enlargement, apomictic auxosporulation, and apomictic (apogamous) auxospore formation. These asexual processes allow small-sized cells to bypass sexual pairing, reorganize their protoplast, and form a large, initial cell. These mechanisms are often reported in specific, particularly centric, diatom species as a way to maintain large populations. Check the glossary for a brief description of these methods.

3 During asexual reproduction (mitosis), all vegetative cell division begins and ends with diploid (2n) asexual daughter cells. When meiosis is triggered in centric diatoms, and two asexual cells prepare for sexual reproduction (meiosis), one cell must be the male and one the female. So, how do these cells decide which will be which? This is how:

Once cell size falls below the critical size threshold, it becomes Sexually Competent, meaning it’s now capable of choosing its sex. In general, a cell chooses “female” if the cell is still relatively larger among the small/competent population making it capable of producing a large egg. But a cell chooses “male” if the cell is relatively smallish in the small/competent population, or if the cell is under stress. One or both of these conditions still enable it to produce 4-128 small, motile sperm.

Now that you’re aware of the factors diatoms consider when faced with such an important decision, and those factors make sense (right?), their “final” verdict is always subject to change. The ultimate determining factor in the sex a compatible pair of diatoms will become as they prepare for meiosis is determined by environmental conditions.

How Long do Diatoms Live?

The answer to this question may not be as straight forward as you might think! Experts who study diatoms (phycology/diatomology) consistently report that an individual diatom cell lives only a short time, usually less than a week. But they’ve also discovered some species can enter a resting stage and will survive for decades or even millennia. Diatom populations can exhibit short duration “blooms” in their populations, while large populations of single and/or multiple species assemblages can be long-lived under the right conditions. So in this section, the lifespan of diatoms is described in several ways, short-term and long-term, and by individuals and populations.

However, before having a specific discussion about lifespan, it seemed necessary to understand how scientists define an individual diatom when compared and contrasted with a diatom population.

Individuals vs Populations

The primary difference between an individual diatom and a population of diatoms centers around scale and ecological function. An individual is a single-celled microalgae with a finite lifespan and size-reduction cycle. A population represents a collective group that drives ecosystem processes like nutrient cycling, genetic diversity, blooms, oxygen production and carbon sequestration.

Some differences characterizing individual diatoms vs their populations

Individual diatom: A single microscopic cell (2–2000𝜇m) encased in a silica cell wall (frustule), with a maximum lifespan of about six days. Reproduction is by mitosis, where the dividing individual (parent) gives rise to two daughter cells that each grow a smaller half frustule inside half of the parent’s donated frustule causing cells to become progressively smaller with each generation. Individuals may be solitary or live in colonies.

Population of diatoms: A massive assemblage (e.g., millions per liter) of individuals of the same or diverse species living in a specific aquatic habitat. A population often contains a wide range of cell sizes due to the progressive shrinkage of individuals, necessitating meiosis to restore the individuals’ maximum cell size, and therefore, the population’s maximum size. Populations are characterized by seasonal “bloom and bust” cycles in high-nutrient conditions. During non-bloom phases, they maintain diversity through sexual recombination. Populations are key primary producers, responsible for 20–50% of global oxygen production and significant carbon fixation.

To summarize, individual diatoms are the basic units of growth, while populations are the functional units of ecosystem processes.

Short-term lifespan of an individual diatom: When sunlight and nutrients are ideal, an individual vegetative cell (the parent) divides by mitosis every 1–6 days, with each division resulting in two new daughter cells genetically identical to the parent, but smaller. Each of these daughter cells, now parent cells, will divide every 1-6 days, producing two new daughter cells each. And on it goes until a critical size threshold is reached triggering meiosis. This rate of reproduction under ideal conditions, especially for species dividing once a day, results in a doubling of their population a minimum of once every 24 hours.

Waxing Philosophical

Is it entirely correct to define the lifespan of an individual diatom as equal to the frequency rate of mitosis of an individual cell (e.g. once a day)? Perhaps an individual diatom’s life is calculated based on the number of daughter cell generations produced beyond the original parent cell, based on passing down halves of the parent’s frustule? From a philosophical standpoint, these types of questions have actually been pondered! I’ll leave you with this one from diatoms.org: “If a parent diatom cell divides and gives one cell wall to one daughter and the other cell wall to the other daughter, does the parent still exist?”

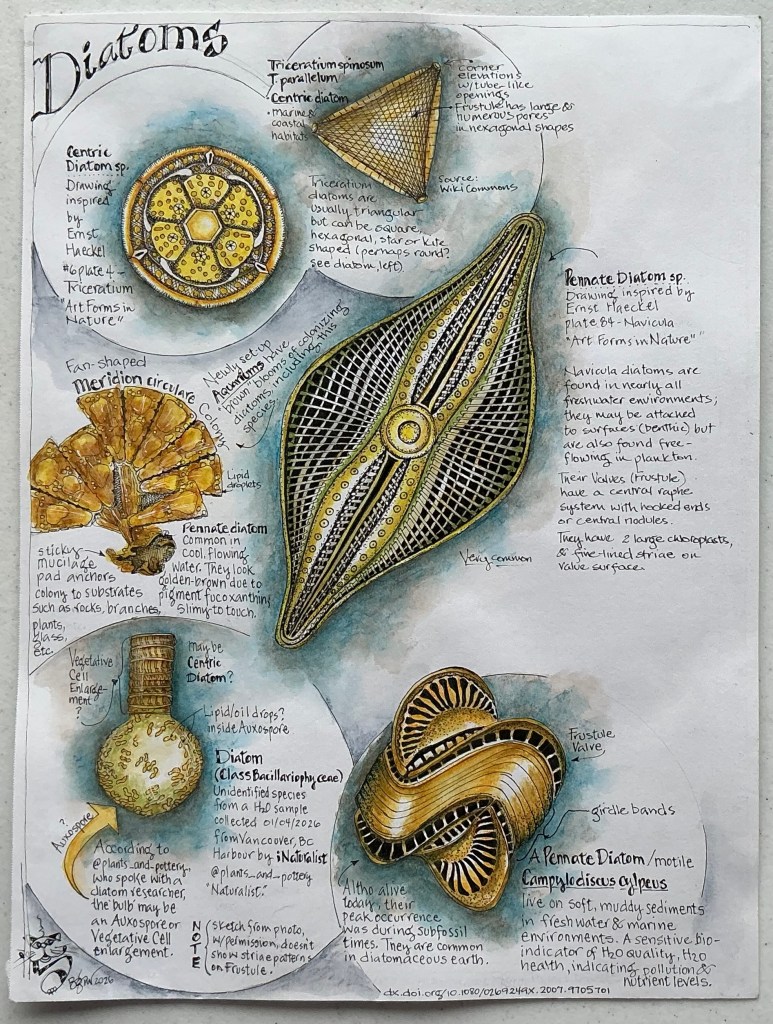

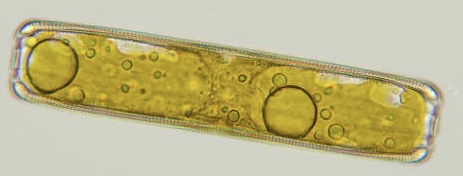

The center of this diatom is where the nucleus lies, along with other organelles, like Golgi bodies and endoplasmic reticulum. To both sides of center are large plate-like yellow-brown chloroplasts (the large brown-ringed circles); 1 per side. Also visible throughout the image are numerous oil bodies (lipids) that look like small round circles. The Pinnularia genus has some of the largest individuals of all freshwater diatoms. This microscopic photo, girdle view, was taken of a live specimen, looking through the transparent frustule, into the cell; 40X (Photo credit ‘Diatom Flora Britain and Ireland)

Short-term lifespan of a diatom population: Diatom “blooms” illustrate well populations that are short-lived. These blooms, coinciding with an overabundance of nutrients and minerals (specifically nitrogen, phosphorus, and silica) and favorable environmental conditions (like high sunlight, warm water, and low water flow), cause diatoms to double their numbers every 24 hours. Their explosive growth, continuing for 2-6 weeks, inevitably depletes one or all of the nutrients and minerals they depend on to live, resulting in a rapid population crash.

A dormant resting state is triggered if (when) the environment they live in becomes too inhospitable.4 Instead of dying, certain diatom species develop resting spores, which gather in deep sea sediments where they remain, surviving for centuries to millennia, patiently awaiting conditions favorable enough to revive them. “We revived hundreds of genetic individuals of diatoms and induced them to start dividing again and to form cloned cultures. The oldest [were] more than 100 years old; the youngest quite fresh. ….. ” said Anna Godhe of the Department of Marine Ecology at the University of Gothenburg. A diatoms’ ability to survive as dormant resting spores for such long time periods, allow scientists to revive them to study past environmental conditions.

Long-term lifespan of individuals and populations of diatoms: Some diatom species form long-lived resting spores that can survive in ocean bottom sediments, allowing individuals and even populations to persist for vast periods of time. They wouldn’t be able to survive if it weren’t for their protective and persistent heavy silica shells (frustules). It’s well known that diatoms’ frustules last for millions of years as fossils, as evidenced by layers and layers of diatomaceous earth. So it’s no surprise that resting spores are able to survive dormant for millennia, displaying their remarkable longevity in geological time.

Therefore, while the lifespan of an actively growing diatom population exists on a scale of days, the population as a dormant, viable seed bank can survive for thousands of years in the sediment. While a living diatom is ephemeral, its durable “glass house” ensures its presence in the Earth’s history for eons. What an incredible feat of resilience!

4 Key characteristics of an inhospitable environment causing diatom populations to crash:

Nutrient Limitation: A rapid bloom quickly exhausts nitrogen, phosphorus, and/or silica, critical for the growth and development of a diatom’s frustule, resulting in a sudden, sharp decline in population.

Ocean Acidification: Acidified seawater slows the dissolution of dead diatom shells, preventing nutrients (silica) from returning to the surface and resulting in a long-term reduction in available nutrients, causing a persistent, and large-scale decline in diatom biomass.

Reduced Vertical Nutrient Mixing: A shallower mixed layer in the ocean limits the availability of nutrients from deeper, colder waters, causing starvation and collapse in diatom populations.

Viral Infection: Viruses can infect and rapidly terminate diatom populations (especially blooming populations) during their stationary growth phases.

Environmental Stress (programmed cell death): Stressors such as extreme light levels, temperature changes, or pollution can trigger programmed cell death (PCD) in diatoms, causing a swift population collapse.

Loss of Biological Turnover: Decreased sediment resuspension, caused by reduced marine life (e.g., groundfish), reduces the supply of silica necessary for new diatom growth.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

It’s a Wrap!

DIATOMS!! MICROSCOPIC LIFESTYLES//Part 3 – The Sequel

Hope you’ve enjoyed learning some fascinating facts about the lifestyles of diatoms. Spread the joy and tell all your family and friends! They will be so impressed with your new-found knowledge of diatoms, and may even want to learn more about these microscopic gems!

………………………………………………………………………………………………

As I was compiling and organizing my notes for Part 3, many additional questions and curiosities about diatoms and their lifestyles popped up. I’d love to know if you came up with some questions as well, and what they were. Also, if you have any questions about or would like clarifications regarding the information in any of my diatom posts, please let me know via message or in a comment to this post.

And now …. a teaser from Part 4 in my Diatom Series – The Good and the Bad

More things I’ve wondered about while researching diatoms:

Are diatoms food?

Are diatoms all good and wonderful? Do they have a bad side?

What do diatoms and the Global Carbon Cycle have in common?

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

(An updated version of the Glossary follows)

If you feel yourself becoming a “Diatomic Geek,” you may find interest in browsing the following Glossary of terms. If a term used within the text of my post is in bold font and italicized, it is (or will be) in the Glossary. (Fair warning: my Glossary continues to be a work-in-progress. Look for an updated version in Part 4 of this series on diatoms.)

Glossary

Allomixis – a specific type of sexual reproduction found in diatoms, representing a mechanism for genetic exchange (cross fertilization). It is a form of oogamy, where small, motile male gametes (sperm) are produced by one cell and move to fertilize a larger, passive female gamete (egg cell) produced by another cell.

Amoeboid gametes – non-flagellated, naked (wall-less) isogamous reproductive cells that move by changing their shape and extending pseudopodium-like projections to locate a partner. They are primarily found in pennate diatoms, where sexual reproduction is typically isogamous (gametes are structurally similar).

Anisogamy – is a form of sexual reproduction in diatoms characterized by the fusion of two gametes that differ in size and/or form, specifically a smaller, usually motile, male gamete (sperm) and a larger, non-motile female gamete (macrogamete or egg). Compare to isogamy and oogamy.

Apomictic (Apogamous) Auxospore formation – In some species, the auxospore develops from a single cell, bypassing sexual fusion, allowing the restoration of cell size.

Apomictic Auxosporulation – Some diatoms produce an auxospore (a specialized enlarging cell) without fertilization or meiosis. This is considered a form of “asexual” sex, where the diploid state is maintained without gamete fusion.

Archaea(ns) – single-celled microorganisms similar in structure to bacteria, but evolutionarily distinct from bacteria and eukaryotes. They are obligate anaerobes living in low oxygen environments (e.g., water, soil), and form a commensal (symbiotic) relationship in ruminant and human intestines. When Archaea is the commensal, it benefits from the relationship with the host without causing harm, or may provide certain benefits to the host (i.e. the human intestines).

Archaeans may be the only organisms that live in some of the most extreme environments on the planet; habitats hostile to all other life forms. Some live near thermal rift vents in the deep sea at temperatures well over 100 degrees Centigrade. Others live in hot springs, or in extremely alkaline or acidic waters. They thrive inside the digestive tracts of cows, termites, and marine life where they produce methane. They live in the anoxic muds of marshes and at the bottom of the ocean, and even thrive in petroleum deposits deep underground. They survive the dessicating effects of extremely saline waters. However, archaeans are not restricted to extreme environments; they are also found, in abundance, in the plankton of the open sea.

Areolae – small, regularly repeated openings in diatom valves (frustule). See definition for pores.

Autotroph (aka Producers) – an organism that produces its own food using external energy sources like sunlight (through photosynthesis) or chemical compounds (through chemosynthesis).

Auxospore – a reproductive cell produced during sexual reproduction (meiosis) by a diatom that has reached the minimum size for its species. The auxospore expands to accommodate the formation of a new frustule, restoring the diatom to the maximum size for it’s species.

Biogenic silica (bSi) – is amorphous, opal-like hydrated silica (SiO2 · nH2O) produced by living organisms, forming structures like diatom shells (frustules), sponge spicules, and plant phytoliths, playing roles in structural support and defense against stress. It’s a key component in marine and terrestrial ecosystems, with significant deposits like diatomaceous earth (DE) from fossilized diatoms.

Biosilicification – the biological process where living organisms take up soluble inorganic silicon (silicic acid, Si(OH)4) from their environment and convert it into solid, polymerized, insoluble silicon dioxide (SiO2) to form hard structures like shells, skeletons, or cell walls, crucial for diatoms, sponges, and plants, and even occurring in some bacteria and mammals. This process is a form of biomineralization, where organic molecules are used to control the precise formation of these silica materials.

How it works – 1) the organism must uptake (absorb) silicic acid; 2) then polymerization takes place, where inside or outside the cell, the silicic acid condenses, forming chains of silica with the removal of water; and 3) specialized proteins and other macromolecules guide (control) this process, creating complex, often intricate silica structures (biogenic silica) like those found in diatom frustules.

Bisecting valvar plane – the imaginary plane that lies parallel to the valve face, separating the diatom into an epitheca and a hypotheca.

Blooms – rapid, seasonal increases in the population density of photosynthetic, silica-encased algae (diatoms) in aquatic environments, typically by high nutrient levels and increased light in spring. Diatomaceous blooms play a crucial role in marine food webs and carbon sequestration.

Carbon fixation – diatoms “fix” carbon by removing inorganic carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere and converting it into organic carbon in the form of glucose (sugar). During this process, oxygen (O2) is released back into the environment, producing 20-50% of the air we breathe.

Catalog of Life – the 1998 Kingdoms of Life were replaced in 2015 with today’s adopted Catalog of Life: At the top most tier or classification rank are two Super Kingdoms, Prokaryota and Eukaryota. The next descending rank includes seven Kingdoms; under Prokaryota are two Kingdoms – Bacteria and Archaea; under Eukaryota are five Kingdoms – Protozoa, Chromista, Plantae, Fungi, Animalia).

Centric – a diatom with valves (frustule) that are radially symmetrical.

Chimeric – (or chimerism) in diatoms refers to the unique, mosaic nature of their genomes and cellular makeup that resulted from their complex evolutionary history, specifically multiple endosymbiotic events. Diatoms possess a mix of genetic material derived from different ancestors, including an ancient heterotrophic host, red and green algal endosymbionts, and bacteria. They arose from two successive endosymbiotic events, when more than 300 million years ago a heterotrophic host engulfed a red alga, which itself contained a cyanobacterial endosymbiont, leading to a complex chimeric genome. The ancestral heterotrophic host provided essential metabolic components, including a complete urea cycle—which is more typically found in animals—enabling diatoms to recover quickly from nitrogen limitation. This genetic mixing is thought to have contributed to their success in diverse, often unstable, aquatic environments.

Chlorophyll – specialized photosynthetic pigments located in a diatom’s chloroplast (plastic). Primarily chlorophyll a and c are the pigments that capture blue-green light energy for photosynthesis. Unlike land plants, diatoms use Chlorophyll c, which combined with fucoxanthin, allows them to efficiently thrive in aquatic environments.

Chloroplast – also called a plastid, a chloroplast is a photosynthetic organelle that absorbs light molecules (sun’s energy) through chlorophyll a & c, turning it into chemical energy by way of photosynthesis.

Chromosomes – thread-like, membrane-bound structures within the nucleus that contain the genetic material (DNA) of diatoms. They are typically organized as diploid (2n) in vegetative cells, and they exhibit unique, highly chimeric genomic features arising from complex, evolutionarily distant origins.

Cleavage furrow – an invagination of the plasma membrane that facilitates cytokinesis following mitosis, pinching the cytoplasm to separate two daughter protoplasts within the parent frustule. Unlike land plants that use cell plates, diatoms utilize this furrowing mechanism, often coupled with chloroplast division, to ensure proper distribution of organelles before new valve synthesis.

Copulation envelope – a temporary, protective mucilage sheath or capsule that surrounds two opposing sexualized pennate diatom cells (gametangia). This envelope is formed to facilitate the sexual reproduction process (meiosis) by keeping the gametangia in close, fixed contact during the pairing and fertilization process.

Cytokinesis – the final step of asexual reproduction (mitosis) where the cytoplasm of a single parent cell is separated to form two distinct daughter cells. Because diatoms are enclosed in a rigid silica cell wall (frustule), their cytokinesis is unique, combining animal-like cleavage with plant-like cell wall construction.

Cytoplasm – the living material inside the silica cell wall (frustule), forming a thin layer around a large central vacuole, containing organelles like chloroplasts, nucleus, mitochondria, and oil (lipid) bodies, often organized in strands, playing key roles in photosynthesis, nutrient storage (lipids/carbohydrates), and locomotion via cytoplasmic streaming, especially in motile (pennate) diatoms.

Daughter cells – the two genetically identical, yet structurally unequal, cells produced during asexual reproduction (mitosis).

Diatom – a microalgae that forms a significant part of the food chain in moist soils and aquatic (marine and freshwater) ecosystems. They form long-chain fatty acids that are an important source of energy-rich molecules and provide a critical food source for the entire food chain, from tiny zooplankton to fish to whales. So it can be said that diatoms feed oceans, lakes, streams, rivers and associated wetlands and riparian areas.

“Diatom” (the etymology) – The word “Diatom” comes from a Greek word ‘diatomos‘ meaning cut into two.

Diatomaceous earth (DE) – a natural, powdery substance composed of the fossilized, siliceous remains of diatoms which lived in water bodies millions of years ago. The silica skeletons these diatoms created accumulated into often vast deposits of chalky, porous sedimentary rock that’s been actively mined since their discovery in 1836 in northern Germany.

Dinoflagellates – single-celled microscopic organisms with two whip-like tails (flagella), making them motile. They are found drifting in large numbers in marine plankton, specifically phytoplankton; also found in fresh water. Some produce toxins that can accumulate in shellfish that, when eaten, results in poisoning. Dinoflagellates form crucial part of the ocean’s food web, producing a significant portion of the world’s oxygen, dinoflagellates are known for causing red tides and bioluminescence.

Diploid (2𝑛) – the life stage of the diatom where its cell contains two sets of chromosomes (2𝑛), forming the dominant, actively growing stage, which produces haploid (𝑛) gametes through meiosis, that fuse to restart the cycle by restoring two sets of chromosomes (

2𝑛) and maximum cell size after sexual reproduction. Compare with haploid.

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) – the “workhorse” of the diatom, responsible for producing, modifying, and transporting proteins and lipids while supporting the complex, four membrane-bound chloroplast structure.

Endosymbiont – an organism that lives inside another organism (its host), forming a symbiotic relationship which is often mutually beneficial (but sometimes one benefits at the other’s expense).

Ephemeral – something that lasts for a very short time.

Epitheca – the larger, outer, and older half of a diatom‘s silica cell wall (frustule). It acts as the lid, overlapping the smaller inner half, known as the hypotheca. Composed of a valve and girdle bands.

Eukaryotes – organisms characterized by complex cells; a membrane-bound nucleus that contains DNA, and other membrane-bound organelles like mitochondria. Eukaryotes can be unicellular or multicellular, fall within the Super Kingdom Eukaryota that includes animals, plants, fungi, and protists (such as algae [like diatoms and seaweed], amoebas, slime molds) The Eukaryotes represent a major group of life on Earth.

Eutrophication – nutrient over-enrichment of water, primarily due to an overabundance of nitrogen and phosphorus, that causes the excessive growth of algae (i.e. diatoms) and other aquatic plants, altering water quality and the ecosystem. This process also alters the transport of silicon dioxide to the ocean. Farming, factories, and people living in cities release a lot of nitrogen and phosphorus into rivers, lakes, and reservoirs. The increased nutrients can cause an overgrowth of algae in those waters and use up a lot of the dissolved silicon dioxide in the water, preventing it from reaching the ocean. The combination of inland eutrophication and damming decrease the total global movement of dissolved silicon dioxide to the ocean by nearly 30%.

Flagella – an appendage that provides motility.

Foraminifera (forams) – a single-celled animal with a perforated chalky, calcium carbonate shell, through which extend slender protrusions of protoplasm. Most forams are marine species – some float in the water column in the photic zone (planktonic); most live on the sea floor (benthic). When benthic forams die, their shells form thick ocean-floor sediments.

Frustule – the external, silica cell wall of a diatom. The frustule is composed of two valves (theca) and the girdle bands. The upper valve (epitheca) is slightly larger than the lower valve (hypotheca). The epitheca overlaps the hypotheca similar to the halves of a pill box or a Petri dish. In diatoms, frustules are not made of pure silica; they also have an organic layer. Its primary component is referred to as biogenic silica. (Read more about the make up of biogenic silica under the definition for silica.)

Fucoxanthin – in diatoms, fucoxanthin is a major golden-brown, light-harvesting carotenoid pigment found in the chlorophyll a/c-binding protein complex, enabling efficient photosynthesis in blue-green light. It’s a crucial accessory pigment allowing diatoms to thrive in marine environments by expanding light absorption to the 390–580 nm range. Fucoxanthin also gives diatoms their distinct golden-brown color, cancelling out the green color from chlorophyll a/c.

Gametangia – specialized, sexually induced vegetative cells that produce haploid (n) gametes. These cells are formed during sexual reproduction (meiosis) when vegetative cells have become too small and must restore their maximum size, a process often triggered by specific environmental cues like light and nutrients. Gametangia are the “sexualized” version of the vegetative cell, transforming from a simple, asexual, dividing cell into a structure focused on producing the next, larger generation.

Gamete – a haploid (n) reproductive cell (sperm or egg) produced during sexual reproduction (meiosis). Gametes (motile, flagellated sperm and immobile eggs) fuse to form a zygote that develops into a large auxospore, restoring the diatom to the maximum species size.

Girdle bands – the bands (aka cingulum) that connect the two valves (epitheca and hypotheca). The girdle bands are visible when viewing a diatom in profile. (Girdle = Copulae)

Girdle view – the profile view of a diatom; view appears rectangular in both centric and pennate diatoms.

Golgi bodies – essential, membrane-bound diatom organelles responsible for trafficking, modifying, and packaging proteins and lipids, particularly for the construction of their silica cell walls (frustules) and the secretion of mucilage.

Glycolysis – is an ancient metabolic process that converts a glucose molecule into two molecules of pyruvate, generating a net gain of 2 ATP and 2 NADH molecules. This series of ten enzyme-catalyzed reactions generally occurs in the cytosol of the cell and can proceed in the presence or absence of oxygen.

Haploid (𝑛) – refers to the stage in a diatom’s life cycle where cells contain a single set of chromosomes, specifically representing the gametes produced during sexual reproduction (meiosis). While the diatom’s vegetative cell (actively growing) is typically diploid (2𝑛), the haploid stage is temporary, brief, and occurs during sexual reproduction to restore cell size and genetic diversity. Compare with diploid.

Heterotrophic – organisms that cannot make their own food and must consume other organisms (plants, animals, or organic matter) for energy and nutrients. Heterotrophs are considered “consumers” in the ecosystem, unlike “producers” (autotrophs) such as diatoms and plants which make their own food. The term comes from Greek words meaning “other” (hetero) and “nourishment” (troph), meaning they rely on external sources for sustenance, such as fungi, humans and most other animals.

Hypotheca – the smaller, inner portion of a diatom’s cell wall (frustule), which acts as the bottom half of a petri dish-like structure, covered by the larger epitheca. During asexual reproduction, each daughter cell receives one parent valve and forms a new, smaller hypotheca.

Initial Cell – the new, full-sized cell formed during sexual reproduction (meiosis) within the auxospore. The initial cell restores the diatom to its maximum size for the species.

Isogamous meiosis – a form of sexual reproduction where diploid (2n) vegetative cells of pennate diatoms undergo meiosis to produce haploid (n) gametes that are morphologically identical in size and structure. Unlike centric diatoms (which are oogamous), pennate diatoms do not produce separate large eggs and small sperm; instead, they produce similar amoeboid gametes.

Isogamy – a form of sexual reproduction found primarily in pennate diatoms, where the fusing gametes are morphologically similar in size and shape. Unlike oogamous reproduction in centric diatoms (which involves large eggs and small sperm), isogamous pennate diatoms produce gametes that are not flagellated and appear alike. Compare to anisogamy and oogamy.

Kingdoms of Life – in 1969, the five major groups of life – aka Kingdoms of Life – were classified as: 1) Fungi, 2) Animalia, 3) Plantae, 4) Protista (the water molds, brown algae and diatoms); and 5) Monera (the bacteria and archaea). In 1990, there were three Domains: 1) Eucarya (including diatoms), 2) Bacteria, and 3) Archaea. Another change was made in 1998, now with two Empires (Prokaryota and Eukaryota) that ranked over six Kingdoms (Prokaryota ranked over one Kingdom, Bacteria; Eukaryota ranked over five Kingdoms: 1) Protozoa, 2) Chromista, 3) Plantae, 4) Fungi, and 5) Animalia.)

Krill – a small marine crustacean living in the world’s oceans. As a keystone species in marine food webs that eat phytoplankton (primary producers like diatoms), they are the main food source for larger animals like whales, seals, penguins, fish and squid, making them vital for the entire ecosystem’s health and energy flow. They also play a significant role in the ocean’s biological pump, transporting carbon from surface waters to the deep ocean through their feeding and waste, helping regulate climate. Krill are plankton but not all plankton are krill.

Lipids – (see oil body)

Marine snow – a sticky, nutrient-rich continuous “snowfall” of aggregates composed mostly of organic detritus—including dead phytoplankton (i.e.diatoms), plankton, plants, animals, fecal matter, mucus, sand and soot — that falls from the upper, sunlit waters to the deep ocean floor. Diatomaceous marine snow forms large (several centimeters diameter) fluffy white and flaky particles in the upper ocean before drifting over weeks to the seabed, transporting and sequestering carbon from the surface and becoming an essential food source for deep-ocean organisms. A similar phenomenon called “lake snow” or lacustrine snow exists in freshwater bodies like lakes and reservoirs.

Meiosis – the sexual reproduction phase of diatoms’ life cycle that converts diploid (2n) vegetative cells into haploid (n) gametes. Meiosis restores maximum cell size through the formation of an auxospore. In centric diatoms, meiosis is oogamous, producing large non-motile egg cells and small motile sperm. In pennate diatoms, meiosis is isogamous (or anisogamous), typically involving the formation of non-flagellated, amoeboid gametes within a mucilage casing.

Metaphase – a stage of asexual reproduction (mitosis) where the cell’s chromosomes condense and arrange themselves in a unique ring or “donut” shape around the equator of a central, cylindrical mitotic spindle. Unlike in most eukaryotes, diatoms undergo “closed” mitosis, meaning the nuclear envelope does not completely break down; instead, the spindle forms within the nucleus, and chromosomes align on this structure.

Microspores – (see sperm mother cells)

Microtubules – hollow, rigid rods that play a critical role in controlling cell shape of a diatom’s cell walls (frustules).

Mitochondria – the energy-producing organelles in diatoms, vital for their survival related to cellular metabolism, including respiration and its link with photosynthesis and carbon fixation, and interactions with the climate system.

Mitosis – is an asexual, closed, and centric process where the nucleus divides within the intact cell wall (frustule), resulting in two genetically identical daughter cells. This division is unique because new valves are synthesized inside existing ones, leading to a reduction in size for one of the daughter cells.

Mucilage – a complex, adhesive, gelatinous substance secreted by diatoms that allows them to stick to surfaces, glide, form colonies, and interact with their environment. Mucilage consists of intricate protein nanofibers and other biopolymers that create strong, extendible attachments, crucial for their motility and survival, often forming visible trails or large-scale gelatinous masses (marine snow) during blooms.

Mucilage during sexual reproduction (meiosis) – a protective, adhesive substance secreted by pennate diatoms to embed and pair compatible gametangial cells. This mucilage serves as a copulation envelope that enables gametes to move toward each other and fuse, facilitating the formation of auxospores.

Oogamous meiosis – a type of sexual reproduction, primarily occurring in centric diatoms, where gametes are highly differentiated by size and motility. It is characterized by the production of a few large, non-motile eggs (female gametes) and numerous small, flagellated sperm (male microspores).

Oil bodies – specialized organelles in diatom cells that serves as primary storage sites for neutral lipids. These organelles, also referred to as lipid droplets or oil droplets, accumulate in response to environmental stress, particularly nutrient and/or mineral deprivation (nitrogen, phosphorus, silicon), and act as energy reservoirs and a carbon sink. Oil bodies are not only inert storage, they are dynamic structures involved in metabolic homeostasis, allowing cells to cope with environmental fluctuations and aiding in buoyancy regulation. Because they are rich in fatty acids, diatom oil bodies are of particular interest for biofuel production.

Nucleus – the membrane-bound genetic center within a diatom cell, usually centrally located or within a cytoplasmic bridge. The nucleus manages cell functions and heredity, and plays a key role in cell division during both asexual and sexual reproduction (mitosis/meiosis). Its DNA is organized into numerous small chromosomes that become visible during division. The nucleus moves to specific sites for cell division (mitosis) and during meiosis, forming daughter nuclei for sexual reproduction.

Oogamy – a form of sexual reproduction (meiosis), specifically found in centric diatoms, characterized by the fusion of two markedly different gametes: a large, non-motile female gamete (egg) and a small, motile male gamete (sperm). This process occurs when vegetative cells have reduced in size below a critical threshold, with the resulting fertilization producing an auxospore that restores the species to its maximum size. Compare to isogamy and anisogamy.

Oogonium – a specialized female vegetative cell that undergoes meiosis to produce one or more large, non-motile eggs (gametes) for sexual reproduction. This process is part of oogamy sexual reproduction, primarily found in centric diatoms.

Organelles – specialized, membrane-bound subcellular structures in the diatom’s cell that evolved primarily through secondary endosymbiosis, resulting in a unique, complex, and highly metabolic cell structure. They’re responsible for compartmentalizing cell functions, including, but not limited to, photosynthesis, energy production, and, notably, silica deposition for their frustules. Key organelles include the chloroplasts (plastids), pyrenoids, silica deposition vesicles, oil bodies (lipid droplets), mitochondria, nucleus, and girdle lamella.

Parent cell – the rigid, silica-shelled organism that divides via asexual reproduction (mitosis), acting as a template for offspring while undergoing size reduction. The parent cell’s two halves (valves) are separated and distributed to the daughter cells, which then form new, smaller valves inside the old ones.

Pennate – a diatom with valves (frustule) that are bilaterally symmetrical.

Phytoplankton – the autotrophic (self-feeding) components of the plankton community. They are photosynthesizing microscopic unicellular organisms, the protists (most notably diatoms) and bacteria (like cyanobacteria), that primarily inhabit the upper sunlit layer of ocean and freshwater bodies. Phytoplankton form the base of those ecosystems’ food web and are significant players in the global carbon cycle.

Plankton – any small freshwater or marine organism that due to its size, immobility, or weakness cannot swim against the current, and exist in a state of drift.

Plastid – a photosynthetic organelle (aka chloroplast) that absorbs light molecules (sun’s energy) through chlorophyll, turning it into chemical energy by way of photosynthesis.

Photosynthesis – the chemical process where plants and some other organisms with chlorophyll, through the use sunlight, combine inorganic carbon dioxide with water to form carbohydrates (glucose/sugars), releasing oxygen as a byproduct.

Pores (areolae) – microscopic openings in the cell walls (frustules) of diatoms that facilitate essential functions like nutrient uptake, waste removal, gas exchange, and mucilage secretion, allowing movement and substrate attachment. The varied sizes and patterns of diatom pores are crucial for taxonomy and optical properties.

Prokaryotes – a microscopic single-celled organism without organized internal structures; they lack a distinct membrane-enclosed nucleus and other specialized organelles. Prokaryotes include the bacteria and cyanobacteria.

Protists – a diverse group of complex Eukaryotes (organisms with a nucleus and organelles) that don’t fit into the categories of animals, plants or fungi. Protists are diverse life forms, mostly single-celled but sometimes colonial or simple multicellular forms, found in aquatic environments. They are incredibly varied, acting like animals (amoebas), plants (algae), animals and plants (diatoms), or fungi (slime molds), and play vital roles in ecosystems as producers and decomposers. Protists are split into two Kingdoms, Protozoa and Chromista, under the Super Kingdom Eukaryota. Diatoms fall under the Kingdom Chromista as described in the Catalog of Life.

Protoplast – refers to the living cell contents of diatoms, including the cytoplasm, nucleus, silica deposition vesicles, oil droplets (lipids), and other organelles, and is contained inside of the rigid silica frustule. The protoplast is the part of the diatom that grows and divides. During vegetative cell division (mitosis) the protoplast duplicates, splitting into two complete daughter cells. But unlike typical plant cells, before the daughter cells separate into two complete diatoms, a new smaller silica valve is formed for each daughter protoplast to pair with their acquired larger parent cell’s valve. Protoplast and protoplasma are used interchangeably.

Pyruvate – a three-carbon organic molecule that functions as a key intermediate in the central carbon metabolism of diatoms, linking various essential metabolic pathways such as glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, respiration, and lipid synthesis.

Raphe – a slit or groove opening in the silica cell wall (frustule) of a pennate diatom to allow it gliding motility and attachment to a substrate by secreting sticky mucilage, allowing these diatoms to move along surfaces and find nutrients.

Red tides – more appropriately described as Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs), occur when colonies of algae—organisms, such as diatoms and dinoflagellates, that live in the sea and freshwater—grow out of control while producing toxic or harmful effects to people, fish, shellfish, marine mammals, and birds. The toxins may also make the surrounding air difficult to breathe. As the name suggests, the algae bloom often turns the water red. One of the best known HABs in the U.S. occurs nearly every summer along Florida’s Gulf Coast. This bloom is caused by a dinoflagellate species producing toxins that kill fish and make shellfish dangerous to eat.

Respiration – a vital metabolic process allowing diatoms to break down organic matter (glucose from photosynthesis) using oxygen (aerobic respiration) or alternative electron acceptors like nitrate (anaerobic respiration, especially in dark/low-oxygen conditions) to generate energy (ATP) for survival, growth, and cell maintenance. Respiration involves pathways like the TCA cycle and glycolysis to balance oxygen production with cellular needs.

Resting spores – specialized, dormant cells designed to survive adverse environmental conditions, such as nutrient depletion or unfavorable light and temperature. Typically asexual, they are a survival mechanism characterized by a thick, heavily silicified cell wall (frustule) and significantly reduced metabolic activity, allowing them to survive for months, years, or even millennia in sediments.

Silica – a mineral, specifically a compound of silicon and oxygen, called silicon dioxide (SiO₂), is one of the most abundant minerals in the Earth’s crust. Silica is most commonly found as quartz, but also in other solid forms like cristobalite, tridymite, and opal.

In diatoms, the living frustules are not made of pure silica. They also have an organic layer. Their primary component is referred to as biogenic silica, a hydrated and polymerized silicic acid compound, similar to the gemstone opal. The biogenic silica is formed within a diatom cell in a specialized structure called the Silica Deposition Vesicle, associated with several organic molecules such as proteins, long-chain polyamines, carbohydrates, and glycoproteins.

Silica Deposition Vesicle – a specialized internal structure of a diatom, where its silica shell (frustule) is built (synthesized) before being exported.

Sperm mother cells – microspores produced when the diploid (2n) vegetative cells of centric diatoms undergo meiosis that become the flagellated, motile male gametes (sperm).

Stramenopiles – a phylum (also referred to as a clade) synonymous with the phylum Gyrista

within the Protista Kingdom. The Stramenopiles (aka Heterokonts) include water molds, brown algae (Sargassum species, Fucus species, and Kelps), and diatoms (centric and pennate forms).

Striae – distinctive, parallel lines or grooves on a diatom’s silica shell (frustule), formed by rows of pores (areolae or alveoli). Striae are crucial for diatom identification (taxonomy) and classification, varying in density (counting the number per 10 µm), orientation (radiating, parallel, convergent), and structure (chambered/unchambered). Striae is the plural of Stria.

Theca – one-half of the diatom silica cell wall (frustule), consisting of a valve and its associated girdle bands. The diatom cell is enclosed by two overlapping thecae: the larger, outer epitheca and the smaller, inner hypotheca, which fit together like a petri dish to provide structural protection.

Vacuole – a large, central, fluid-filled sac within the diatom cell, often occupying most of the cell’s interior and is surrounded by the cell’s cytoplasm. The vacuole acts as a storage organelle for nutrients and contributes to buoyancy and cell volume regulation.

Valves – the cell walls of diatoms are made up of two valves; top (epitheca) and bottom (hypotheca). The top valve is slightly larger so it overlaps the bottom one like a pill box or Petri dish.

Valve view – the view of a diatom when looking face-on at one of the two valves.

Vegetative cell – a diatom cell that reproduces asexually through mitosis, dividing its protoplast (cell contents) to form two new cells, each inheriting half of the parent’s silica shell (frustule) and building (synthesizing) the other smaller half, resulting in smaller daughter cells. These photosynthetic, unicellular diatoms are crucial in aquatic ecosystems by fixing carbon and producing oxygen.

Vegetative Cell Enlargement (VCE) – In certain species, cells can partially or completely remove their cytoplasm from the restrictive silica frustule, expand in size, and secrete a new, larger shell.

Vegetative stage – the diploid (2n) asexual, photosynthetic, and metabolically active cell that make up the vast majority of the diatom life cycle.

Zygote – a diploid (2𝑛) cell formed after sexual fusion (fertilization) of two haploid (n) gametes which typically occurs when vegetative cells have reduced in size below their critical threshold. The zygote immediately grows and matures into a large specialized cell called an auxospore.