A Battle of Wits

Conflict of Interest

November 24, 2025

Were you ever so challenged by something so clever, while at the same time so frustrated with something so beautiful? No, no, wait….. that question may be more complicated than need be. Let me put it this way ……

Were you ever at your wit’s end finding a solution to a seemingly simple problem that you thought was obviously and repeatedly staring you right in the face?

My reply? Yes!

It’s All About the Genes

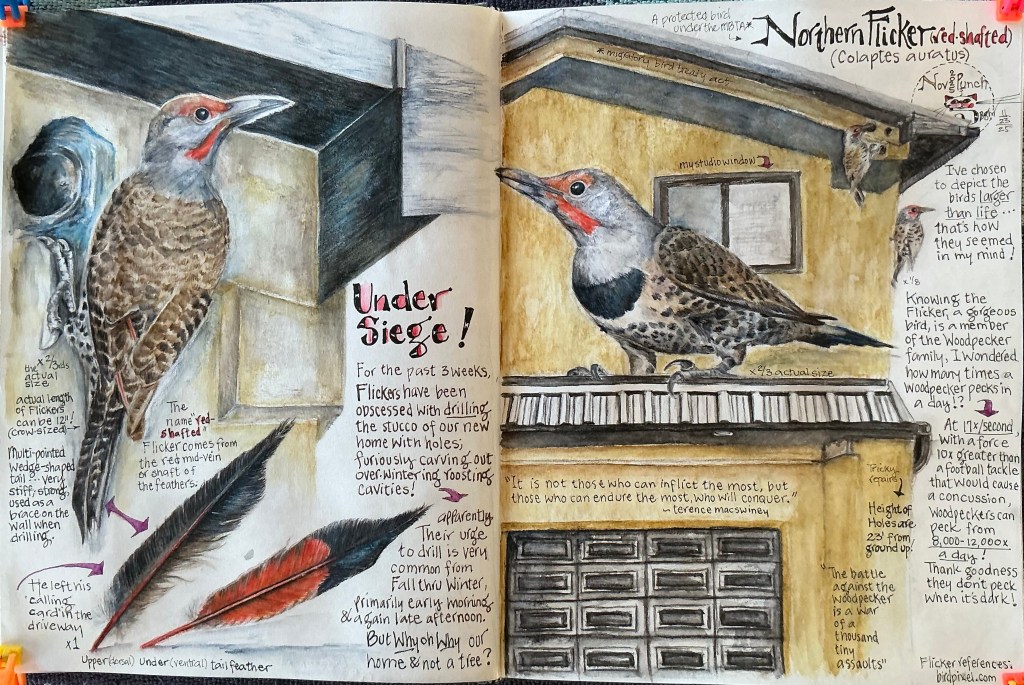

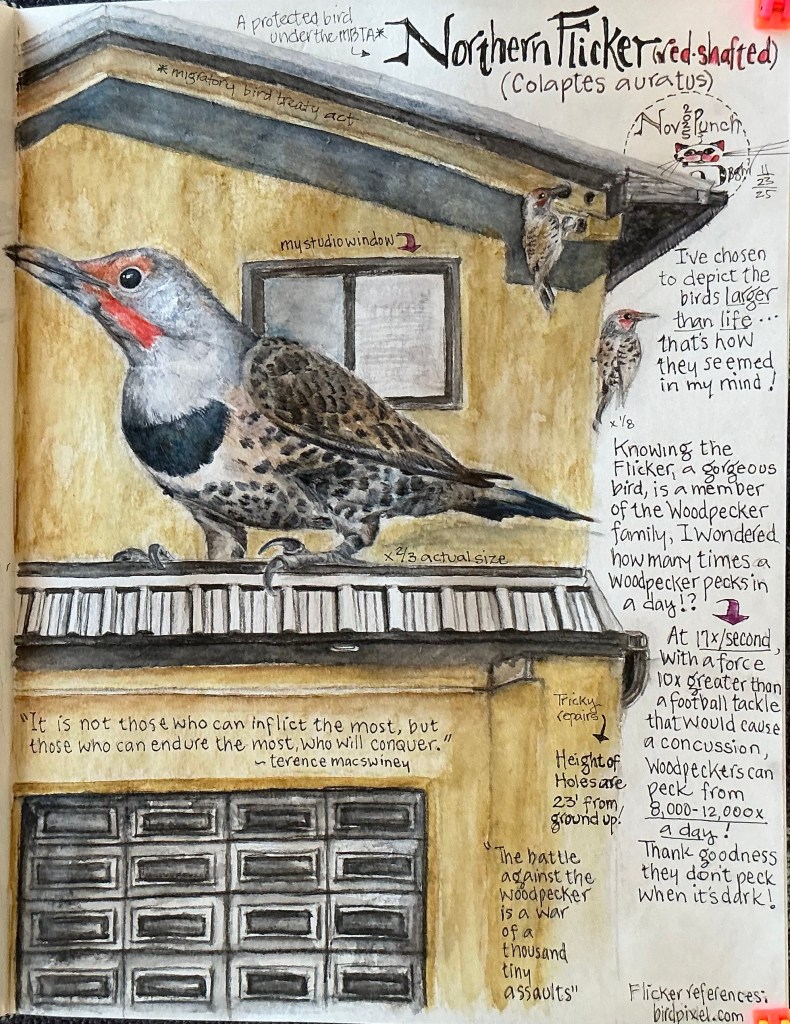

Meet the Northern Flicker (Colaptes auratus) … or more specifically, the Western red-shafted flicker (C. auratus ssp. cafer)*, a gorgeously flamboyant and noisy member of the Woodpecker family, that’s common throughout its western range.** And as woodpeckers do so well, they peck and peck and hammer and drill with the determination and force of a jackhammer*** on nearly any vertical (preferably wooden) surface. They’re single-minded, from start to finish, when it comes to creating a cozy nesting or roosting cavity, whether in a tree trunk or into your home. (More about that in a bit.)

Flicker ID – 101

How do you know a Flicker has laid claim to your place? Well, he’s a big, heavy-bodied bird, and when flying overhead, your first thought might be “Crow!” At 12-14” long, with a wingspan of 18”-21”, the size is right. But as he flashes a large showy white rump patch bookended by reddish-orange underwings, you realize he’s not black. Anything but! As his flight slows and dips you notice his brown back is marked with narrow black bars. In preparation for landing, with wings open wide, he vertically aligns his body and feet with the wall, exposing a pale gray belly with bold black spots and a chest-wide black patch. Two strong clawed-toes up, two down (zygodactyl), and a stiff wedge-shaped tail adjusted as a brace, he taps out a few test spots, drawing your attention to his long and heavy bill, on a slate gray head broken by a buff-brown crown, a bright red whisker (male), and light gray cheeks.

On a crisp cool Autumn morning, as you watch in horror ……

Before you can declare, “It’s a Male Flicker!” ……

This bigger-than-life bird has landed, tested, and pecked away at his chosen spot 170 times in 10 seconds! He’s created an entry hole about 3” wide, right through the stucco and foam sub layer. This determined Flicker knows winter is coming and he intends to drill into our home, making a cozy roosting cavity in which to hunker down until Spring!

Oh no, No, NO!

We love Flickers and have no wish to harm this beautiful bird.**** But he’s already caused enough damage (23 feet high on the wall) that needs immediate repair. So I clap my hands and holler loudly (something unintelligible), and off he flys to a nearby snag to see how serious my noise-making was.

That’s the story of Flicker hole #1

Oh Not Again, and Again, and Again!

Since early November, our resident Flicker (I call him Jack), has continued to return many times, usually between sunrise and 10am. Sometimes he’ll make a fly-by before sunset. Often his quiet arrival escapes our notice; either we’ve been running errands, we’re out hiking with Luna, or enjoying a short roadtrip. These are the times he’s been able to drill six 3”-wide holes on the initial wall, and another 3”x6” hole just around the corner which was so deep, he almost penetrated the interior of Roy’s woodshop! This gives a whole new meaning to the term “Airbnb!”

After a few weeks up and down our fully-extended extension ladder to make a 2-step/2-day repair job/hole, we were making ZERO headway. Jack, unable to resist the need to drill him a roost cavity, was always one hole ahead of us. And because he didn’t hesitate to redrill newly repaired holes, was there something we were doing wrong?

It’s an Education in Biology and Patience

So we learned to listen for his noisy “kerrreee” scream-like call announcing his presence from one of Jack’s many favored perches around the house. Unless we missed it, his territorial call would put us on high alert, ready for action. We also listened for his series of warm-up test pecks that usually sounded inside the house. This “alarm” would catapult one or both of us from a comfy chair and run outside yelling and clapping our hands.

Between listening, running, clapping and yelling (and wondering what the neighbors might be thinking), I discovered a few interesting things on-line…..

- Woodpeckers can’t resist drilling holes in synthetic stucco. This product provides the perfect surface for woodpeckers to hammer. When they begin tap pecking, it creates a hollow sound because the synthetic stucco includes a foam layer. The woodpeckers peck through the hard outer surface into the foam where it is easier to create a larger cavity to nest.

#1 …. Our entire home happens to be covered with synthetic stucco! While this might explain Jack’s insatiable desire to drill his roosting cavity into our home and not into one of the surrounding hardwood piñon pines, we’re not going to replace the stucco.

- Basil, mint, cinnamon and/or lavender are suggested as natural, non-toxic deterrents for woodpeckers, who dislike strong aromas. The scent of basil, in particular, can be overwhelming and confusing to woodpeckers. Crushing one or a mix of these herbs with adding a bit of water, creates a green slurry that can be filtered and applied with a spray bottle to the affected area(s).

#2 …. This idea was worth a try, especially since there’s still have basil and mint growing in the garden. After collecting several handfuls of each, I popped the mix into the food processor with a bit of water and flipped the on switch. Gathering the resulting slurry, I filtered it through paper towels and collected the liquid for a spray bottle. That was several weeks ago, and with every hole repair, Roy’s been thoroughly soaking first the patch job then follow-up stucco coating with the basil/mint spray. It’s hard to know if it’s actually working, but the initial drilling sites haven’t been redrilled in the past week. It could also be that Jack is gone; pushed out with one of our heavy rainstorms. Or he’s begun drilling more recent holes over the RV garage door. With each repair, Roy continues to spray the basil/mint mix.

- The Federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act*** provides protection for Flickers (and all woodpeckers), making it illegal to harm or kill them. But when warranted, migratory birds can be killed under a depredation permit issued by the Law Enforcement Division of the USDI-Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). Authorization by the relevant state wildlife agency also may be required before lethal control methods are initiated. Sound justification must be present for the issuance of depredation permits.

#3 …. Applying for a depredation permit may be our last resort, if Jack and his cohorts threaten to turn our brand new home into Swiss cheese.

AGAIN!

That’s the story, almost. This clear Conflict of Interest; an obvious Battle of Wits, continues. Just yesterday, one of the holes Roy patched above the RV garage door was redrilled this morning!

Oh Good Grief!

It’s already been repatched and resprayed, and while writing this story in my studio with window cracked and a clear view of the patched hole, I’m sure to hear and see that gorgeously determined Flicker if he returns to jackhammer away, once again, into a side of our home!

I’d love to know if you or anyone you know has a proven solution to this natural dilemma. Meanwhile …..

Thanks for stopping by, and Happy Thanksgiving!

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………

*Northern Flickers are divided into 2 subspecies, the Western red-shafted flicker (C. auratus ssp. cafer) and the Eastern yellow-shafted Flicker (C. auratus ssp. auratus). The red-shafted subspecies is found throughout Mexico, western and west-central U.S. (where it is common all year long), and British Columbia, Canada. The closely related yellow-shafted subspecies, which is highly migratory, is found in eastern and east-central U.S., the Canadian provinces and Territories (except B.C.), and far north into AK.

**Where the range for both subspecies overlaps (in the ‘lower 48’), a lot of hybridization occurs. It’s common to see a red-shafted flicker with more orange feather shafts and/or shades of yellow-orange on the underside of their flight feathers. The same holds true for the yellow-shafted hybrid. Otherwise, appearances differ notably between both subspecies of the Northern Flicker, primarily where the malar (mustache), nape pattern (back of the head below the crown), face color, and tail and flight feathers are concerned. See the table below for non-hybrid subspecies characteristics. For hybrids, any color and pattern variation(s) and combination(s) you can imagine have probably been found!

| Northern Flicker subspecies | Red-shafted | Yellow-shafted |

| Face color | Gray | Buffy to warm, light brown |

| Malar color | Male: red Female: brown | Male: black Female: brown |

| Nape color & pattern | Gray, unpatterned | Male: Red crescent on gray Female: gray, unpatterned |

| Feather shaft/under flight feathers | Pinkish to reddish to red | Yellow |

***A woodpecker can peck wood 17x/second, and from 8,000-12,000x/day! Really! And they can drill into wood at a force 10x greater than a football tackle that would cause a concussion. On the November 17, 2025 episode of the Science Friday (SciFri) podcast, biologist Nick Antonson stated that woodpeckers can peck 20-30x their body weight. Now that’s amazing for a Flicker that weighs about 6 ounces!

****Because we had no desire to harm the Flicker(s) drilling into our new home, even when we reached our point of extreme frustration, we wanted to ensure our deterrent efforts aligned with wildlife regulations; especially with the Federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act (Act). Flickers (and all woodpeckers) are considered a migratory non-game bird species, and protected under the Act. It’s illegal, punishable by fine and/or imprisonment, to harm or kill them.