April 23, 2025

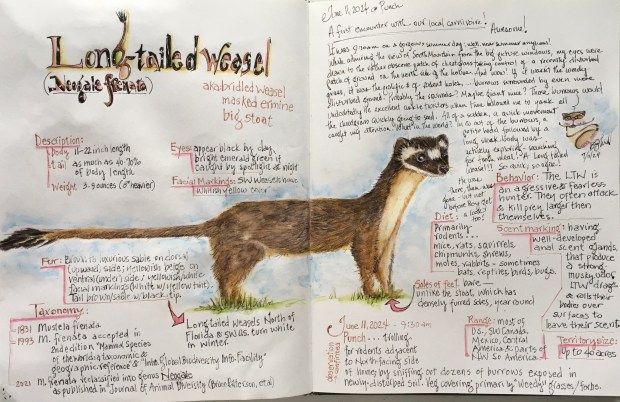

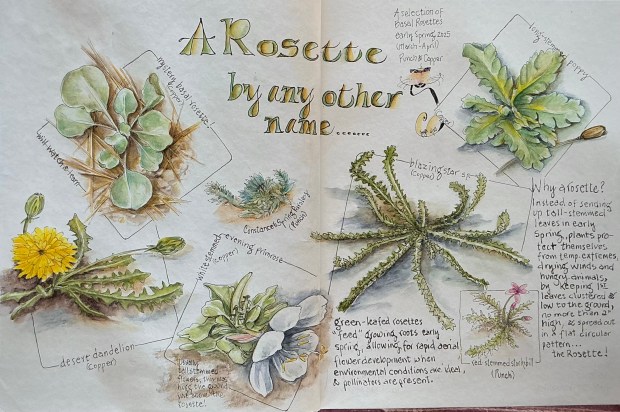

Have you ever noticed a dandelion? Oh sure …… you’ve seen hundreds, probably thousands of those ubiquitous sunburst yellow flowers blanketing a lawn or brightening an abandoned field. But before all that brilliance magically appears, have you ever looked below all those flower stalks? Have you ever noticed a dandelion before it blooms?

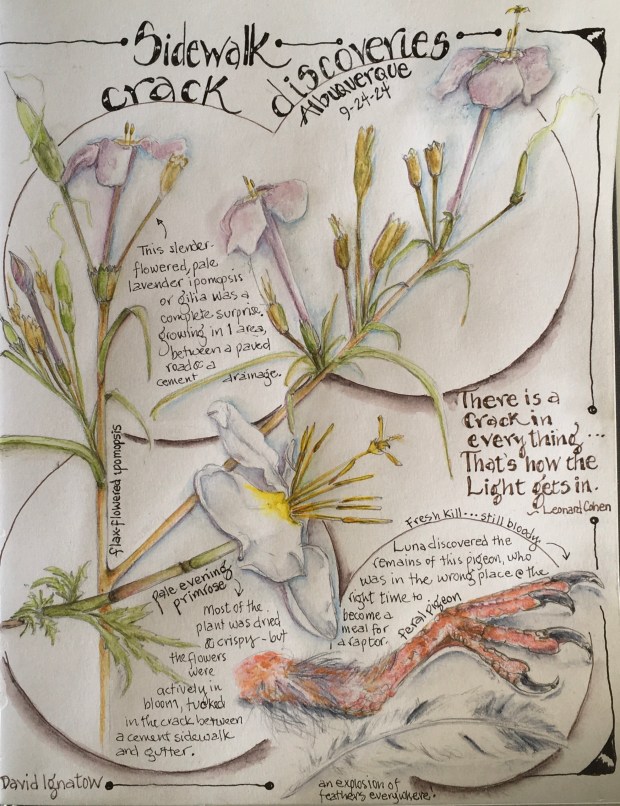

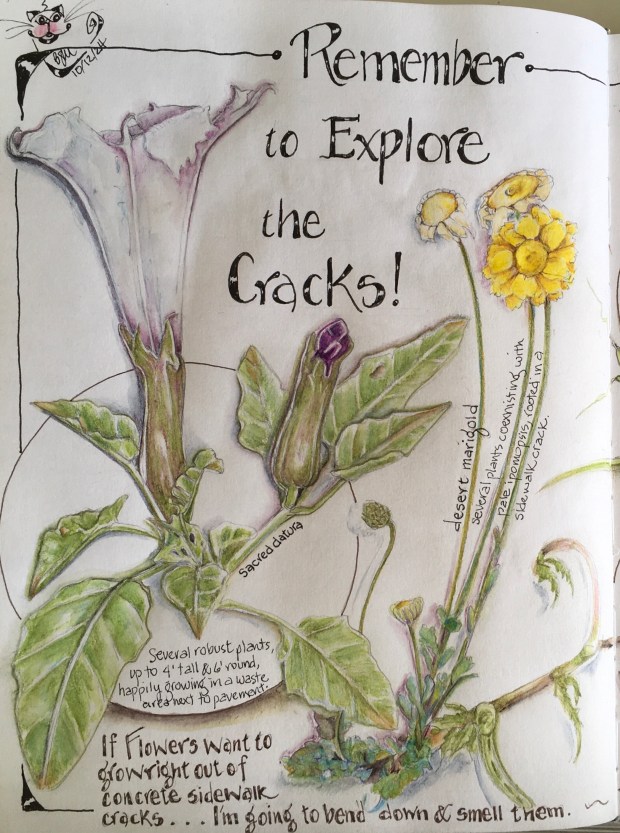

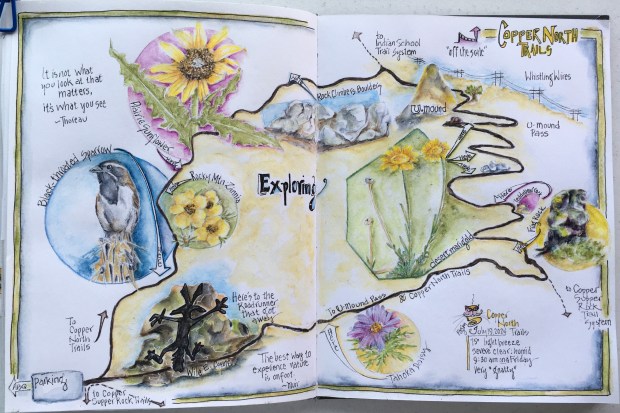

It’s early Spring in the mountainous areas of central New Mexico, and it seems like the high desert is slow to bloom this year. Anxious to spot even a hint of green during this transition time is always challenging, but if you look closely …….. Tucked beneath dry grasses and piled-high tumbleweed skeletons wedged next to swelling cholla you’ll find the green. Clusters of new leaves hugging the ground no more than an inch high, are beautifully arranged in a circular pattern like the unfolding petals of a rose.

Rosettes!

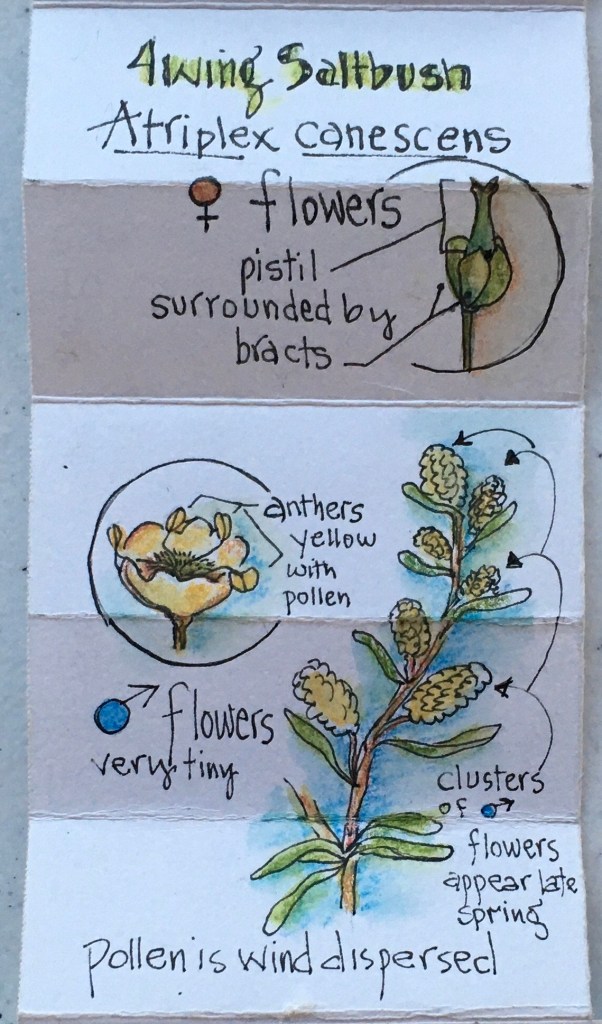

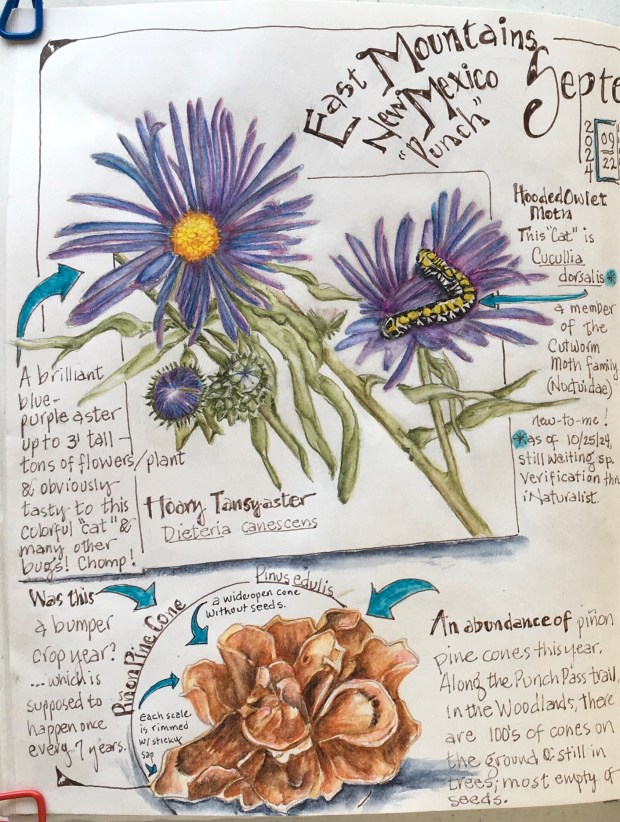

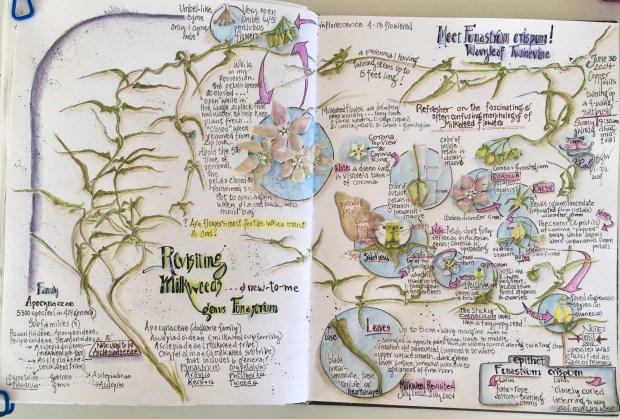

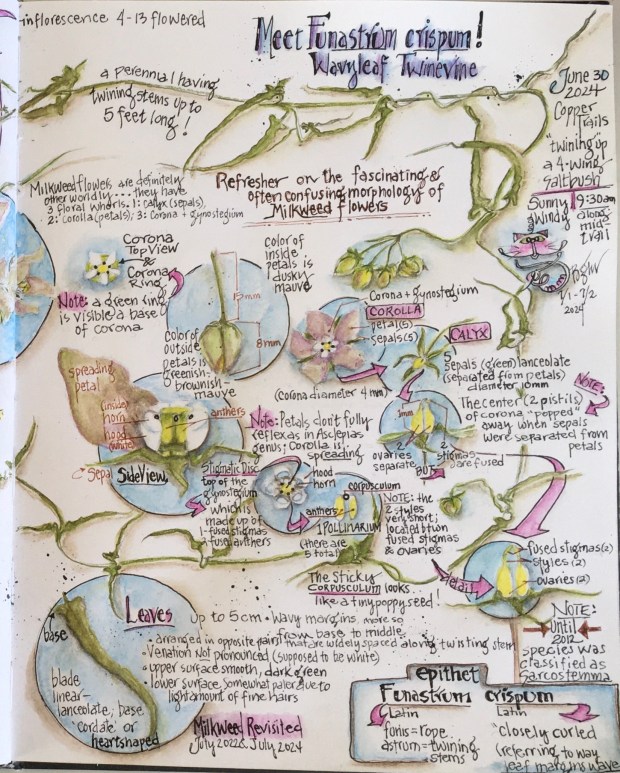

Rosette arrangements are found throughout nature,1 but in the flowering plants they are particularly common in the following families: Asteraceae (like dandelions), Brassicaceae (like cabbage), and Bromeliaceae (like pineapple). Many other families display the rosette morphology too. The needle sharp leaves of yucca and the bayonet-shaped leaves of century plant (in the Agave family) form tall rosettes. The intricate leaves of wild spring parsley (a tiny member of the Parsley family) and the petite red-stemmed stork’s bill (Geranium family) both form ground-hugging rosettes.

Where Rosettes Form

Basal Rosettes grow close to the soil at or near the plant’s crown (the thick part of the stem where the roots attach). Their structure is an example of a modified stem in which the internode gaps between the leaves do not expand, ensuring all the leaves stay tightly bunched together and at a similar height. A protective function of a basal rosette makes it hard to pull from the ground; the leaves come away easily while the taproot is left intact (have you ever tried to pull a dandelion without snapping off the root?). Generally speaking, basal rosettes improve a plant’s odds at survival. For example, overwintering rosettes, like the basal leafy growth produced in year #1 of the 2-year life span of giant mullein, protect the plant and its roots from extreme cold temperatures. Emerging Spring rosettes, like those found in long-stemmed poppy, also protect the plant from late winter frosts. Basal rosettes are also more protected from changes in microclimate, gravity, wind, browsing, and mechanical damage if they are closer to the ground than tall leafy stems would be. help in water balance and conservation, especially important during periods of drought.

But don’t only look down. Another form of rosette occurs when the internodes (those areas between leaves) along a stem are shortened, bringing leaves closer together as in lettuce and some succulents.2. And although not as common as basal rosettes, some plants form rosettes at the terminal or top end of their often naked stems, branches, or even trunks. One plant that does this is the native sedum called wild stonecrop. The top of the plant stems usually terminate in whorls or three fleshy leaves. Another example is the Hawaiian screwpine, which has a terminal rosette of sword-shaped leaves which sits atop an erect trunk, often supported by prop roots.

Know Your Local Rosettes

A number of desirable and undesirable (weedy) plant species produce rosettes, particularly basal rosettes. Being able to identify a species that pops up in the Spring by its rosette is so helpful in preventing a removal mistake by inadvertently digging them up. Many weedy, non-native plants gaze first at their world through rosette “eyes.” But not all plants with rosettes are undesirable. Do you know your local rosettes by their other names?

………………………………………………………………

1 Rosettes are found throughout nature, not just in the flowering plants. Here’s some examples you may have seen or heard of:

In bryophytes and algae, a rosette results from the repeated branching of the thallusas grown by plant, resulting in a circular outline. Lichens also grow rosettes.

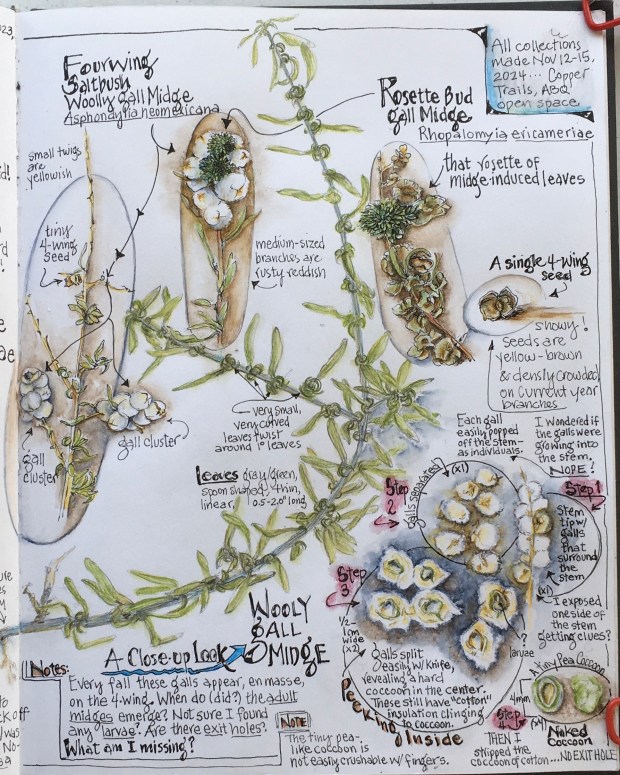

Tiny wasps and midges can induce the development of galls that become leafy rosettes.

Jaguars, leopards and other feline species display rose-like markings on their fur, referred to as rosettes.

Malaria parasites are known to form spontaneous rosettes in uninfected red blood cells.

Neural rosettes in the human brain are being studied to learn how new cells are born.

It is unknown why the Rosette-Nosed Pygmy chameleon, at home in the mountains of Tanzania, has evolved a distinctive, rosette-shaped, fleshy protrusion on the end of its nose.

The Rosette nebula, named for its rosette-like appearance, is a beautiful collection of gas and dust 5,200 light-years from Earth in the constellation Monoceros the Unicorn, and stretches about 130 light-years across.

2 The horticultural definition of a succulent describes a drought-resistant plant where the leaves, stems, or roots have become fleshy and their tissues are able to store water. Succulents include aloe, euphorbia, sedum, the garden favorite hen-and-chicks, and bromeliads. But horticulturalists do not include cacti in the succulent group. huh? Even though cacti are frequently found in books describing succulents based the definition of a succulent, succulents are not cacti. In agreement with that last statement are many botanical and other scientific experts. (Can this get any more confusing?). So basically some experts are lumpers, while other are splitters. Which are you?

P.S. Cacti have stems that are thickened fleshy water-storing structures, and are considered to be a stem-succulent group of plants. Are there any cacti species that develop leafy rosettes? Because the spines are the leaves, greatly modified, in all my rabbit-trailing thru the internet and perusal of my collection of botanical references I’ve yet to see any spines forming whorled/rosette-like patterns. If you have, please contact me immediately!

……………………..……………..😂…………………………………………

Are you ready to explore the wide diversity of rosette forming plants in your neighborhood? Get on out there before those circularly-arranged leaves become disguised by an overabundance of gorgeous wildflowers!

As always, thanks for stopping by! And Happy Earth Day (week)!