December 7, 2025

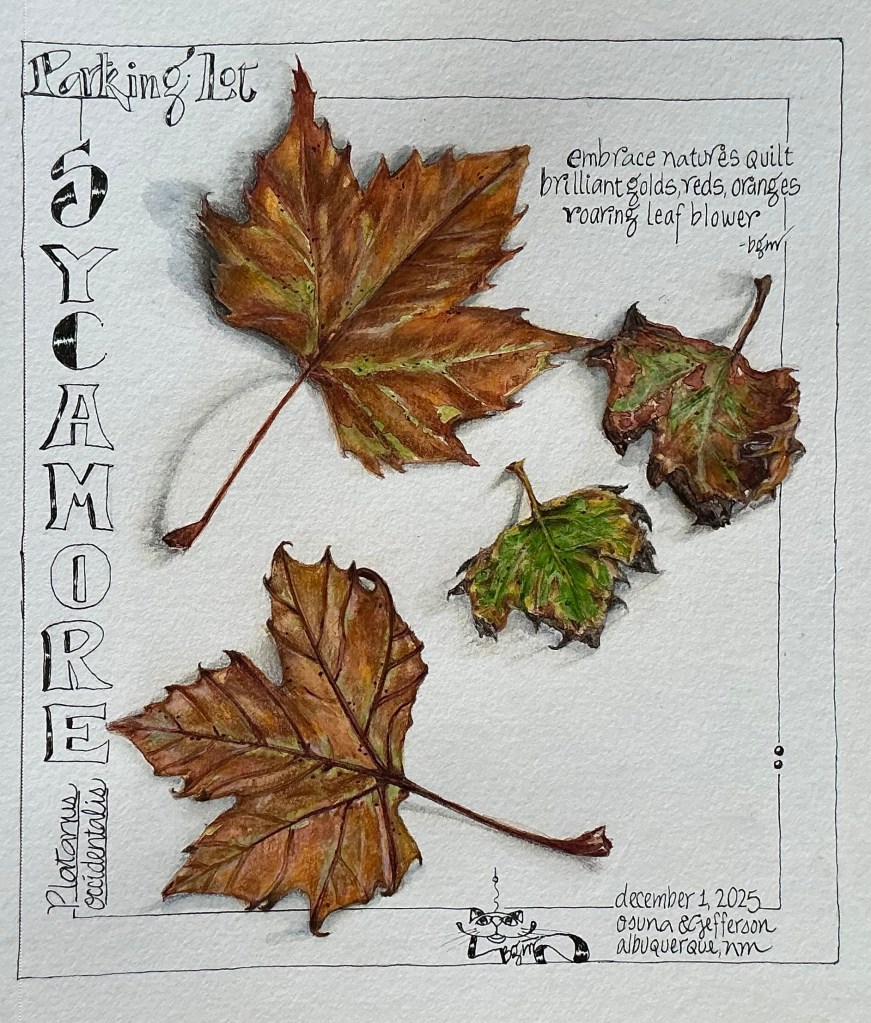

My search for still-beautiful Autumn leaves, half hanging, half fallen to the ground, took me to Albuquerque where temperatures hadn’t yet dipped below zero. Striking ‘gold’ in a large vacant parking lot next to a Disc Golf course, are at least 30 full-grown Sycamore trees with what looked to be full canopies of foliage still clinging tight. But for all the leaves yet to fall, there must’ve been 50x that number covering the ground. The morning breeze was causing the recently-fallen leaves to skid across the pavement in jerky movements, coming to rest in the parking lot’s gutters.

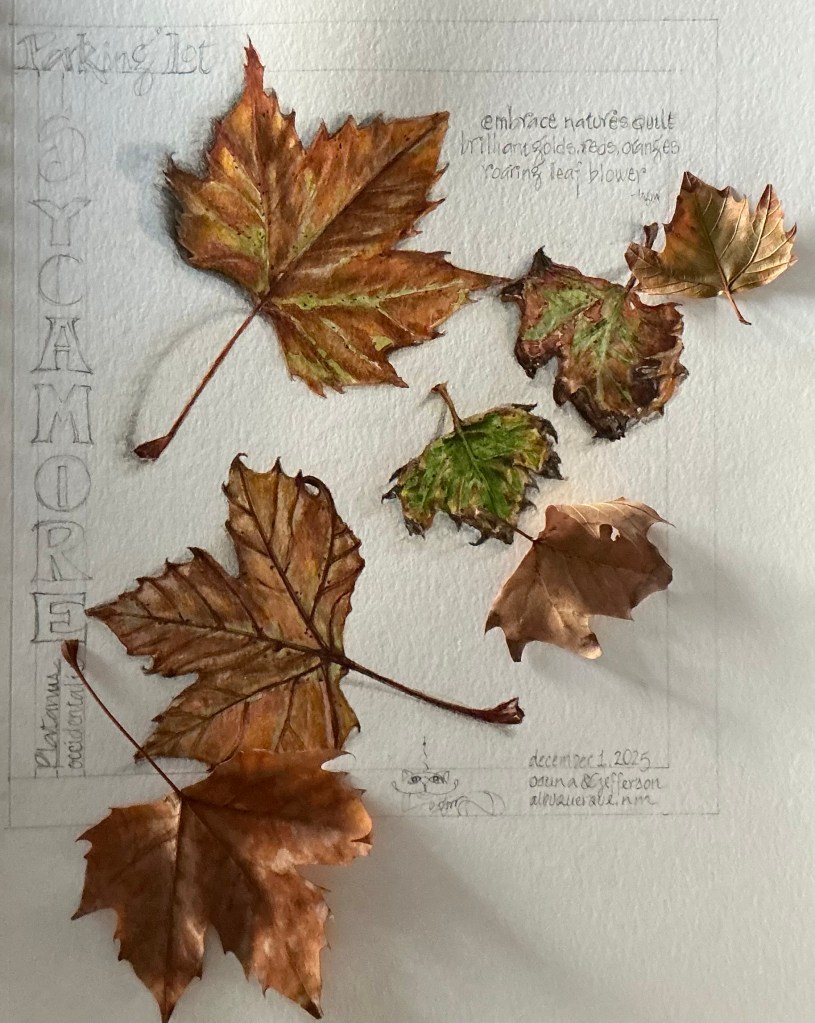

It was in these ankle deep gutter piles where the range of leaf sizes, colors and patterns were found. These 1” to 10” broad, palmately veined and ragged-toothed leaves appeared locked together like pieces from a newly-opened 5000 piece jigsaw puzzle. And, oh my! The lid to the box just blew away! Now I was faced with a dizzying jumble of multi-colored golden-yellows, burnt oranges, Ruddy duck rust, fading-to-spring greens and saddle browns. It was from these ankle deep gutter piles that I collected Autumn leaves for this project.

Lost in thought, I overlooked the white noise of the city ……. traffic mostly, constantly humming and impatiently honking ……. until a painful ringing in my ears invaded the relative calm of the morning. No longer able to think, I turned around and found an invasion of leaf blowers! Never was there a more loudly screaming, obnoxiously noxious sound. Coming closer and closer, louder and more insistent, their ear-muffled and gas-masked operators approached without hesitation, each blowing away (to where?) every bit of the “unsightly and offending” leaf-litter in their path.

Dang-blasted!

It finally dawned on me this Friday morning that the vacant parking lot only opened for use on Sunday’s. Not agreeable to working weekends, the leaf blower operators were determinedly cleaning up the “messy” lot for the regular Sunday crowd. I was in their way.

Saving as many fallen Sycamore leaves as my collection bags could hold, and silently wishing all remaining leaves a happy landing somewhere on a nutrient-needy plot of land, I ran for the quiet of my car.

My Fallen Leaf Project

Using Sycamore leaves collected from that vacant Albuquerque parking lot, I tried my hand at a new technique; combining watercolor layers with layers of colored pencil. Using my new set of Van Gogh watercolors, I began each leaf with a layer of plain water followed by a light base layer, mixing Azo yellow medium with a touch of Yellow ochre. The bottom leaf (which was the underside of the top leaf) was duller and lighter in color, calling for a bit of Permanent lemon yellow. Allowing that layer to dry, I used various earthy colors from my set of Faber-Castell Polychromos colored pencils over the watercolor wash, mixing and matching the colors of my pencils with the actual leaf colors. This step tended to leave some areas uncolored with the pencils, so I applied another watercolor wash with Sap green, Burnt Sienna+Yellow ochre, and/or Madder lake deep+Azo yellow medium. I finished each leaf with a Dark sepia colored pencil outline, tipped the leaf margins with Dark sepia, and added shadowing first with Payne’s grey watercolor then Dark sepia colored pencil.

The leaves were painted on 140# Canson XL Watercolor paper

If you have and questions or comments, please let me know. If you use this combined media technique, any tips you’d like to share would be greatly appreciated too.

…………………………………………………………………………………………

I’d like to send a shout-out and my deep gratitude to Wendy Hollender, botanical artist/illustrator/teacher extraordinaire, who announced in her newsletter free access for over a week to 19 of her bite-sized video lessons. Designed as companions to her book, The Joy of Botanical Drawing, each lesson focused on a different botanical subject and how to artistically render them using watercolor and colored pencil combined. I’ve always wanted to learn this technique and gave it a try with her leaf examples and then mine. Incorporating both media into the same painting was very challenging and way out of my comfort zone.

Thanks so much Wendy, for such wonderful lessons and your fabulous companion book! With lots more practice, my goal is that some day my botanical art looks as natural, skilled and professional as yours.

…………………………………………………………………………………………

As always, Thanks for stopping by!