October 13, 2025

Today is the second Monday in October ….. a day to pause and honor the deep roots, rich cultures, and enduring spirit of the first peoples of this land. Native American Day celebrates the history, contributions, and resilience of Native American tribes all across the nation.

Yesteryears

Native American Day honors all Native Americans. South Dakota led the way, officially changing Columbus Day to Native American Day in 1990 after a “Year of Reconciliation” was declared by Governor George S. Mickelson. California soon followed. In recent years, the movement has gained national momentum. Many states and cities have chosen to celebrate Indigenous Peoples’ Day on the same date. Then in 2021, President Joseph Biden issued the first-ever presidential proclamation for National Indigenous Peoples’ Day, marking a significant step in acknowledging and respecting the history and contributions of America’s first inhabitants.

Present-day

Celebrating the second Monday in October is more than acknowledging the past ….. it’s a day to recognize the living cultures that continue to enrich our country’s tapestry. It’s an opportunity to move beyond stereotypes and learn about the diverse traditions, languages, and stories that have shaped this continent for millennia. Native American Day also highlights the efforts to revitalize and preserve hundreds of indigenous languages, each one a unique expression of culture and knowledge. When we celebrate Native American Day, we celebrate the incredible diversity of traditions. Instead of a single culture, there are hundreds of distinct nations, each with its own unique customs.

Storytelling and Art Making

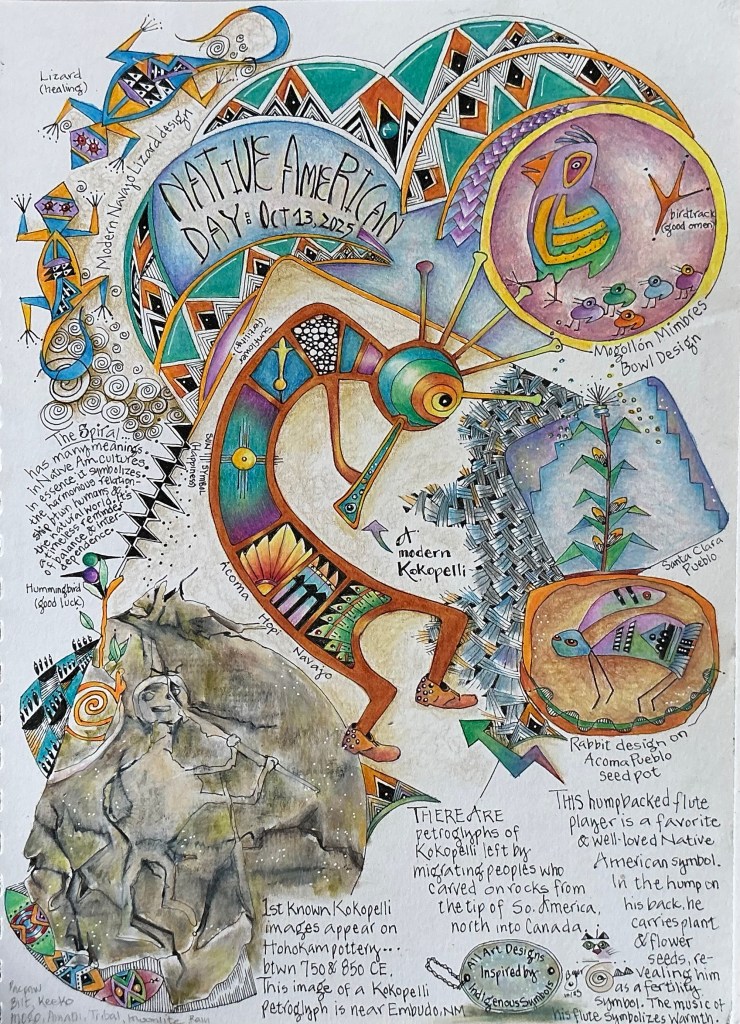

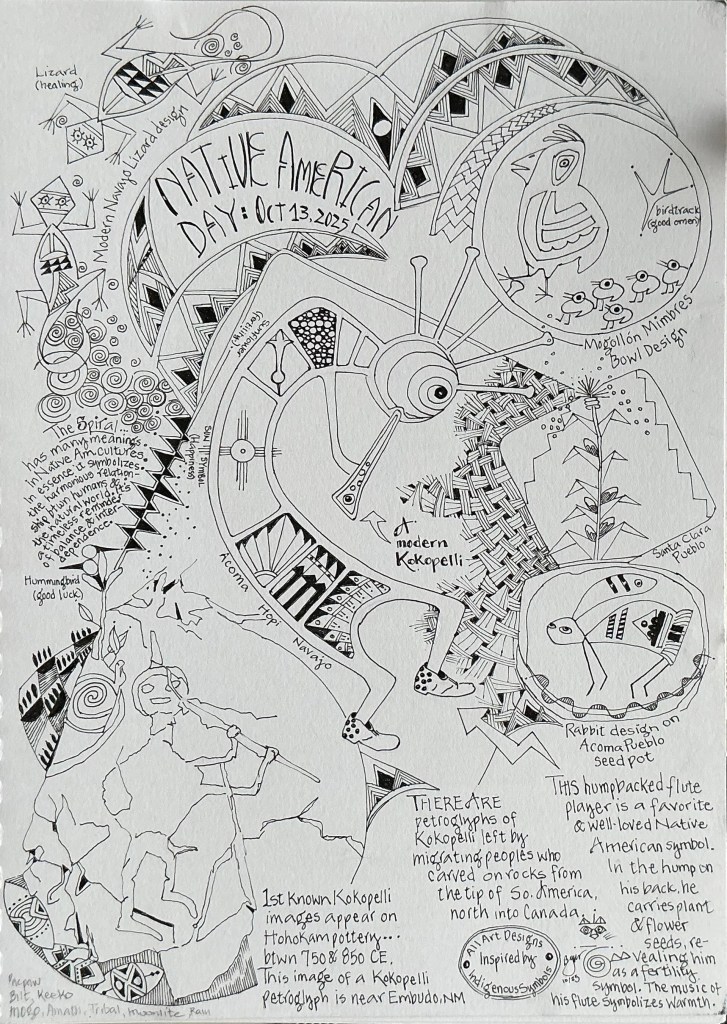

Native Americans have a powerful storytelling tradition of oral history, where foundational stories, lessons, and legacies were and still are passed down through generations. Many of these stories of life and culture are told through artwork, from ancient pictographs (rock paintings) and petroglyphs (images cut into rocks by pecking, incising or abrading) created by the indigenous peoples that lived throughout America, the intricate beadwork of the Plains tribes, the iconic pottery of the Pueblo peoples of the Southwest, to contemporary painting and sculpture. Native art is a cornerstone of American culture.

New Mexico Rock Art

Images painted on and carved into rock that were used in ancient storytelling can be found throughout my home state of New Mexico. Many of these sites are protected and preserved by federal designation as National historic landmarks, National Parks, and by the Bureau of Land Management as Areas of Critical Environmental Concern, and as a significant part of our Archaeological heritage.

Traditional cultures and customs continue to fascinate me, and in “drawing” attention to the important contribution rock art has and continues to play, I wished to shared some of the designs (symbols) created by Native American tribes indigenous to the 4-corners region of the Southwest, with focus on those found in New Mexico. The Kokopelli symbol, the dancing flute player, is a familiar and favorite character throughout the area and has many meanings tied to fertility and harvest. The symbol depicted shows Kokopelli with a hump in his back where he carries seeds ready for planting, while he plays his flute, a symbol of warmth. He also carries a sunflower disk flower (the ‘complete’ inflorescence) to display fertility, the Sun symbol for happiness, and several crop symbols designed by the Acoma, Hopi, and Navajo.

The very first known Kokopelli images appeared on ancient Hohokam pottery, dating from between 850 and 750 C.E. The drawing of the Kokopelli petroglyph, in the bottom left of my panel, is inspired by one of these first images that was discovered near Embudo, NM.

Ideas to Celebrate Native American Day ….. Learn, listen and engage by …..

.…. reading a book by a Native American author, such as Louise Erdrich, Sherman Alexie or Tommy Orange,

….. exploring a museum or a state historic site to learn firsthand about the lives and history of the region’s tribes,

….. purchasing authentic arts, crafts, and goods from Native artists, which directly supports and helps preserve their cultural practices,

….. attending one of many community- or university-hosted talks, film screenings, or celebrations such as a powwow

Thank you very much for stopping by!