July 23, 2025

When you think of ‘Barberry,’ does a shrubby knee-high landscaping bush that transforms to flame red in the fall, come to mind? If so, you may have seen hedge rows of the plant known as Japanese barberry ……

Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii) is a non-native shrub that was introduced from Japan in 1875 as an ornamental that’s planted for erosion control and as a living fence. But this invasive shrub outcompetes and displaces native plants, alters ecosystems, and is a host species of black-legged ticks that carry Lyme disease.

When you think of ‘Holly,’ does a plant with boughs of prickly green leathery leaves naturally ‘decorated’ for the holidays with red berries, come to mind? If so, you’re likely familiar with the iconic American holly ……

American holly (Ilex opaca) is a native shrub of eastern and south-central U.S. that grows well in both dry and swampy soils. The plant, which is also cultivated as an ornamental, forms thick a canopy cover for birds and other wildlife, and the female plants produce an abundance of shocking red berries, loved by birds but poisonous to dogs, cats and humans. Regardless of the risk, bountiful quantities of leafy boughs and clusters of red berries are harvested each fall and brought indoors to create holiday wreaths and other seasonal decorations.

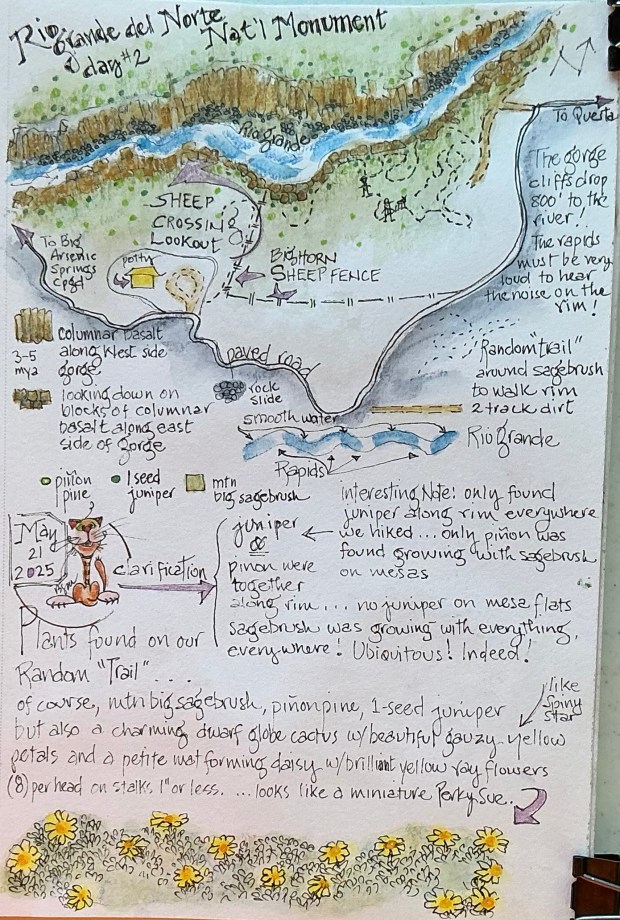

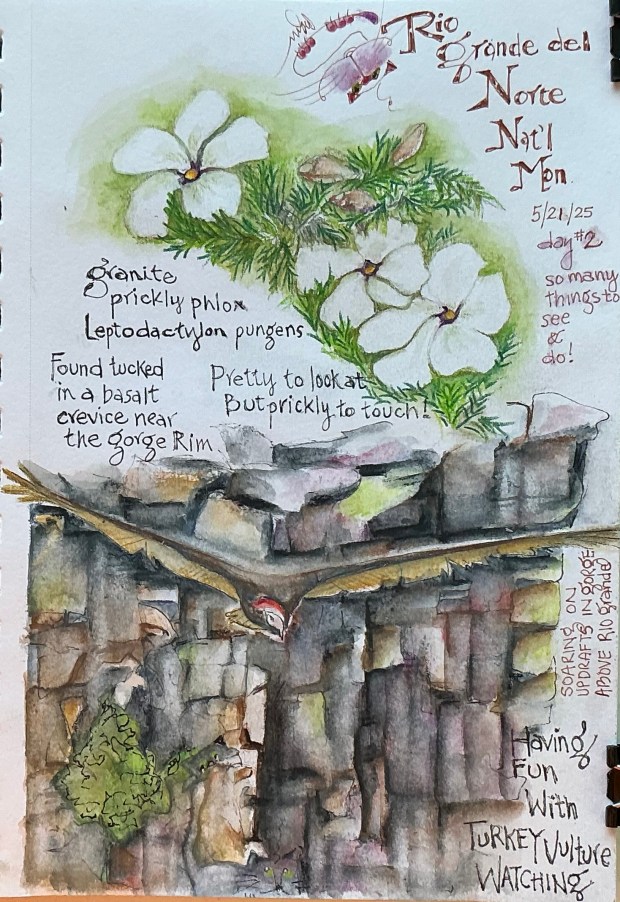

Now imagine you’re hiking in a pinyon-juniper forest of the American Southwest. You decide to bushwhack to a connecting trail and all of a sudden find yourself hopelessly stuck in a 10 foot high shrub covered in juicy red berries and very prickly holly-like leaves. This large (somewhat familiar) shrub is a surprisingly effective barricade; a formidable fence. You’ve become entangled in thousands of armed leaves preventing your forward or backwards movement without getting seriously poked and stabbed!

Is this the desert variety of American holly? Maybe it’s the giant living fence of a Japanese barberry gone rogue?

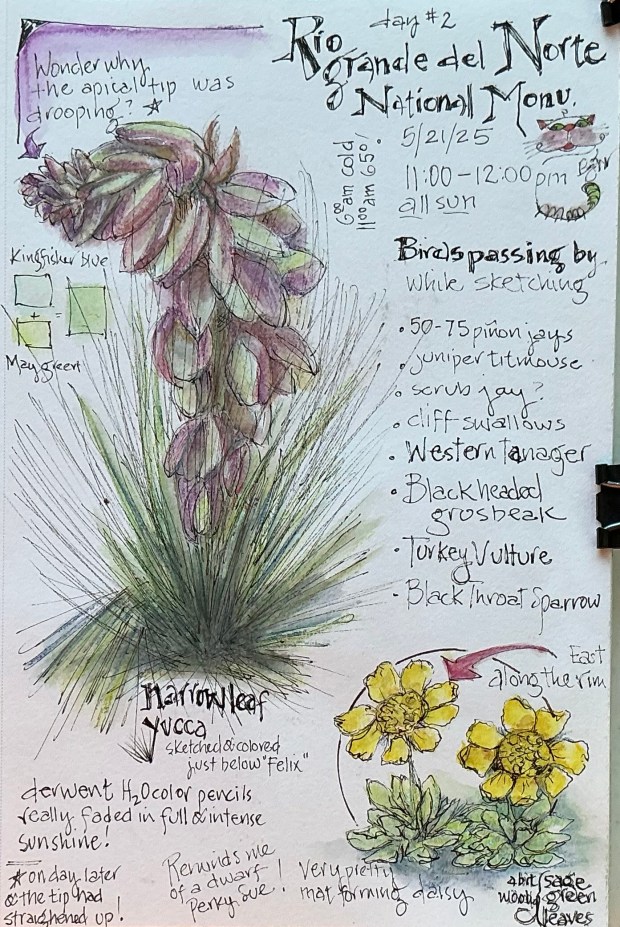

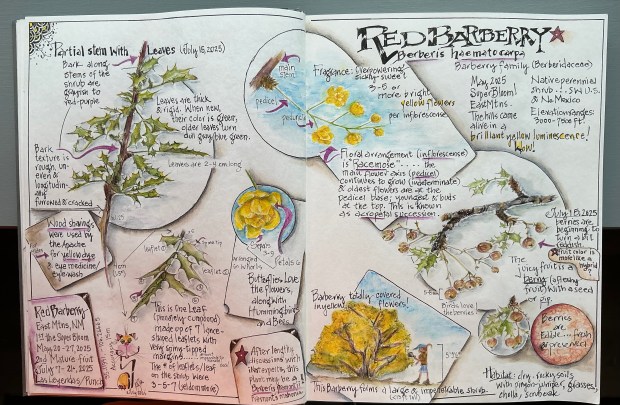

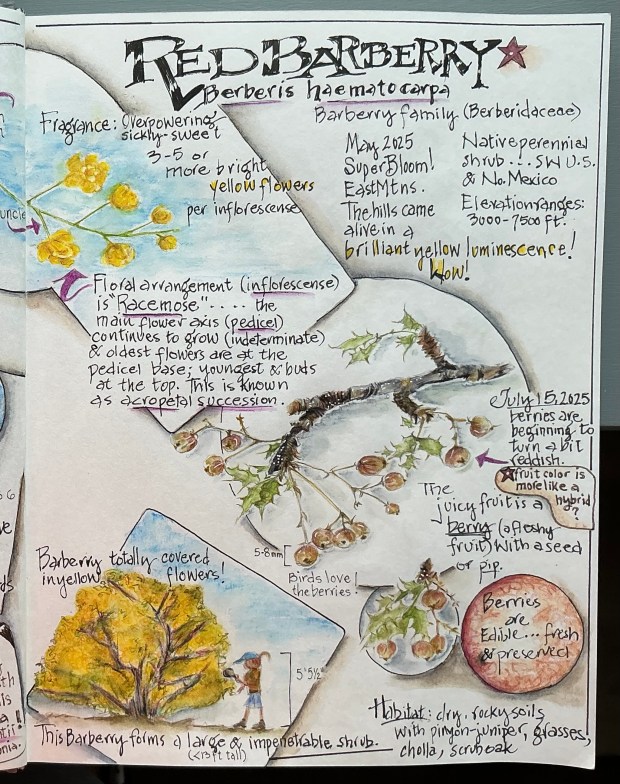

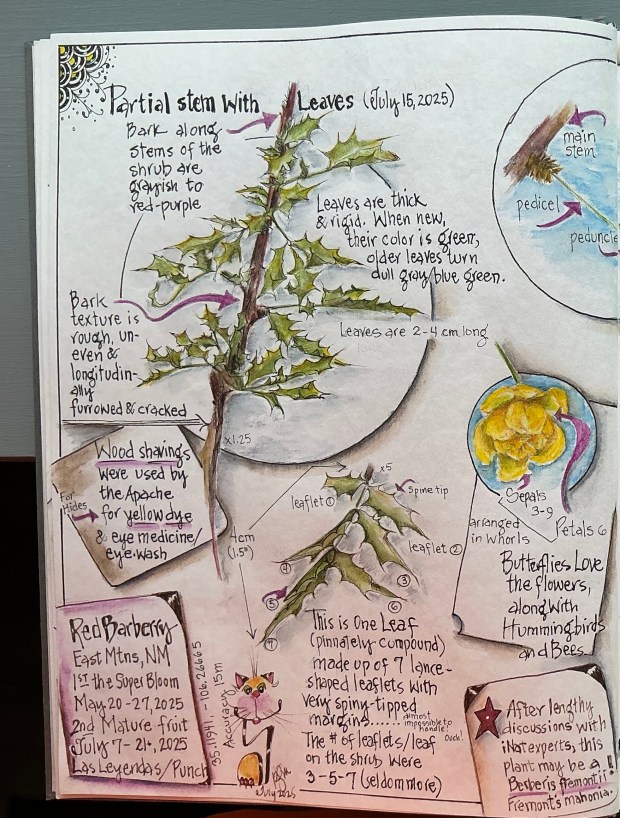

Nope! It’s neither. You’ve stumbled upon (into) a hardy specimen of the desert Southwest native Red Barberry (Berberis haematocarpa). But no wonder you were confused. This shrub, which can grow to 13 feet tall and nearly as wide, has an abundance of holly-shaped leaflets armed by a sharp spine on each lobe tip. And if birds haven’t devoured all of the red berries, you may find an ample supply of a refreshing (albeit tart) snack while you carefully and oh-so-slowly free yourself from the shrub’s embrace.

By now you’ve created lasting memories of Red Barberry, and have promised to always be alert for surprise encounters when visiting the desert island Southwest.

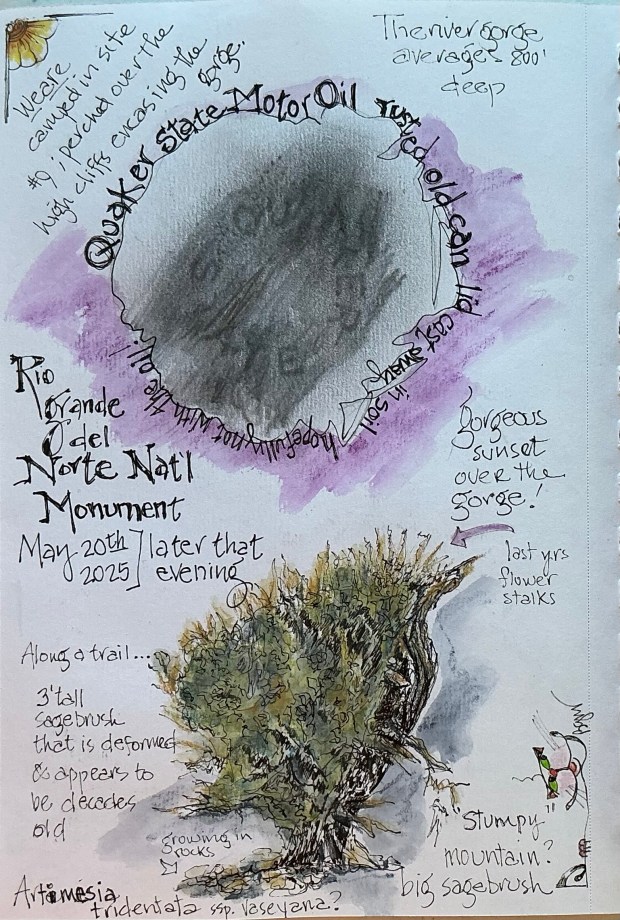

The hiking scenario above conjured up one of my hard-learned lessons from 8 years ago. Having just moved to New Mexico, Roy & I began avidly hiking local trails. Wishing to master the native flora as quickly as possible, one day I discovered clusters of red berries hanging inside the leafy canopy of a 5 foot shrub. What could they be?! Only having eyes for those juicy berries and an irresistible urge to gather a bunch for closer inspection, I plunged my open hand through several layers of small leaflets and successfully clutched a cluster. It was then I realized those spiny leaflets had poked, scratched and even penetrated my bare skin, as evidenced by tiny trickles of blood dripping from my hand and arm! Now that I had captured those pretty berries, it was obvious they had to be released to permit me the delicate maneuvers required to free my arm and minimize further injury. It was that day that I learned all about Red Barberry; lessons that will likely stick with me always!

Since that close encounter 8 years ago, it’s no surprise I’ve never been a big Red Barberry fan, until ……

…… this past May a 13 foot tall plant in front of our home burst out in the most spectacular display of sunshine yellow flowers, literally covering the entire shrub front to back; top to bottom! The fragrance was overwhelming for the entire 2+ weeks the flowers were in bloom. And not only our Barberry was in full bloom, but about a dozen more barberries in our neighborhood and surrounding area were also covered in vibrant yellow. It was an amazing sight, causing me to figuratively re-embrace the native Red Barberry!

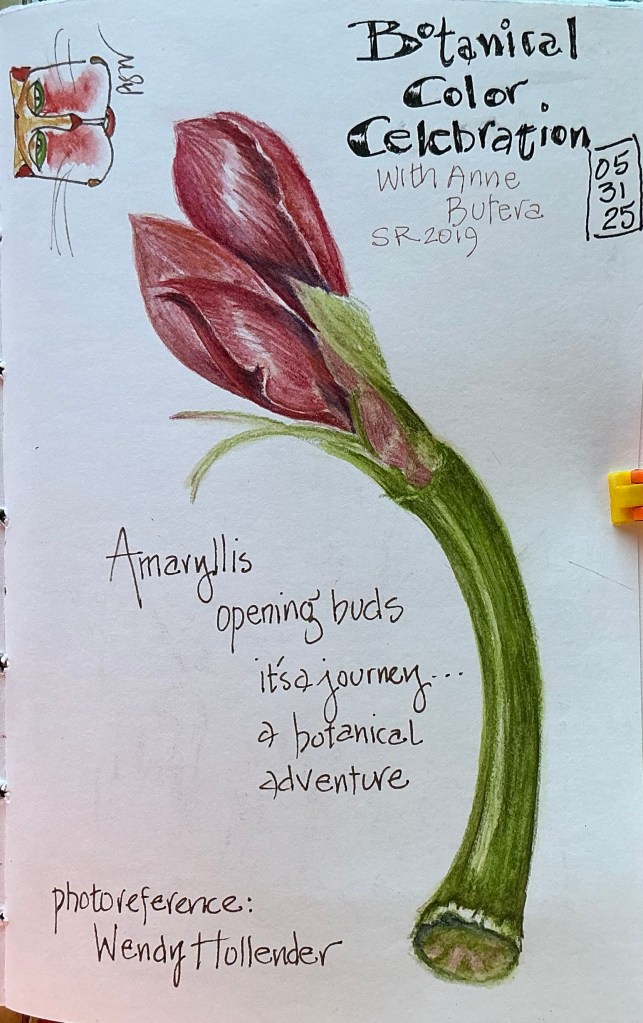

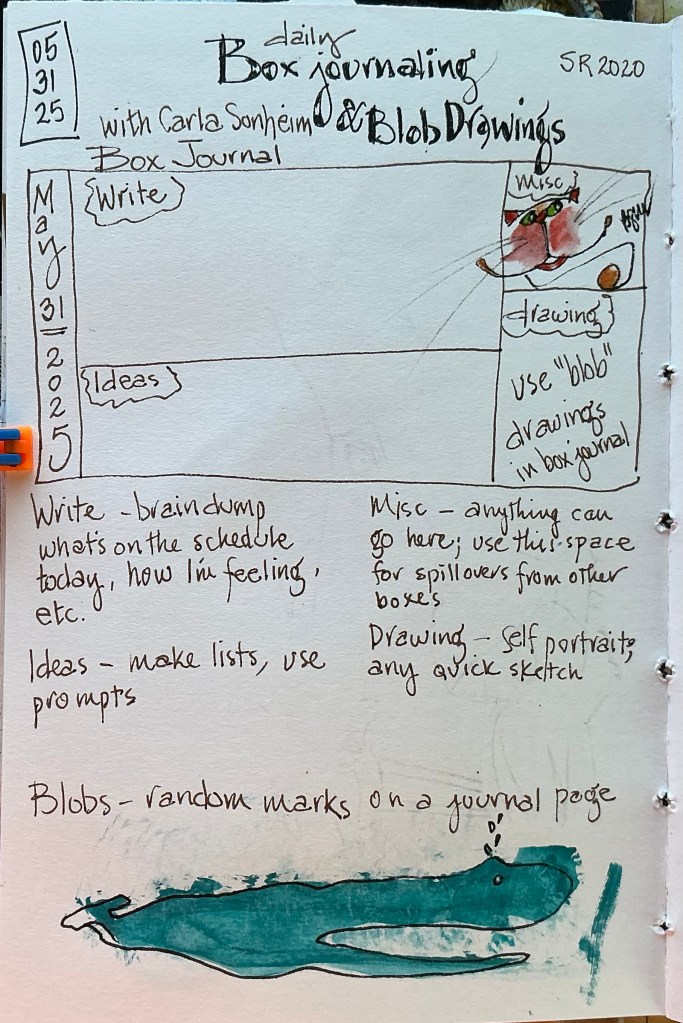

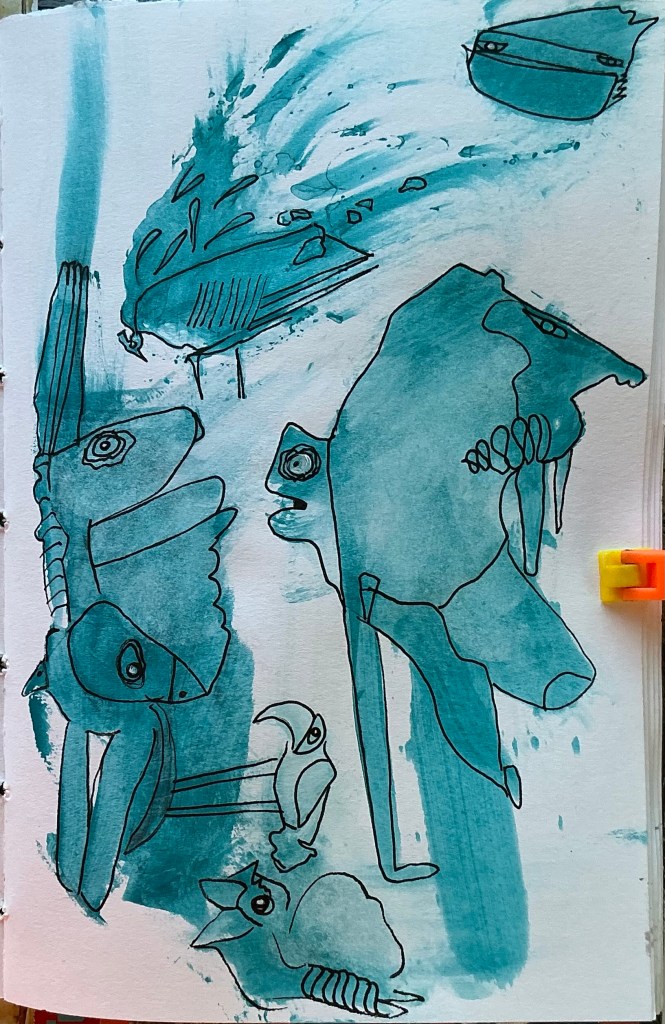

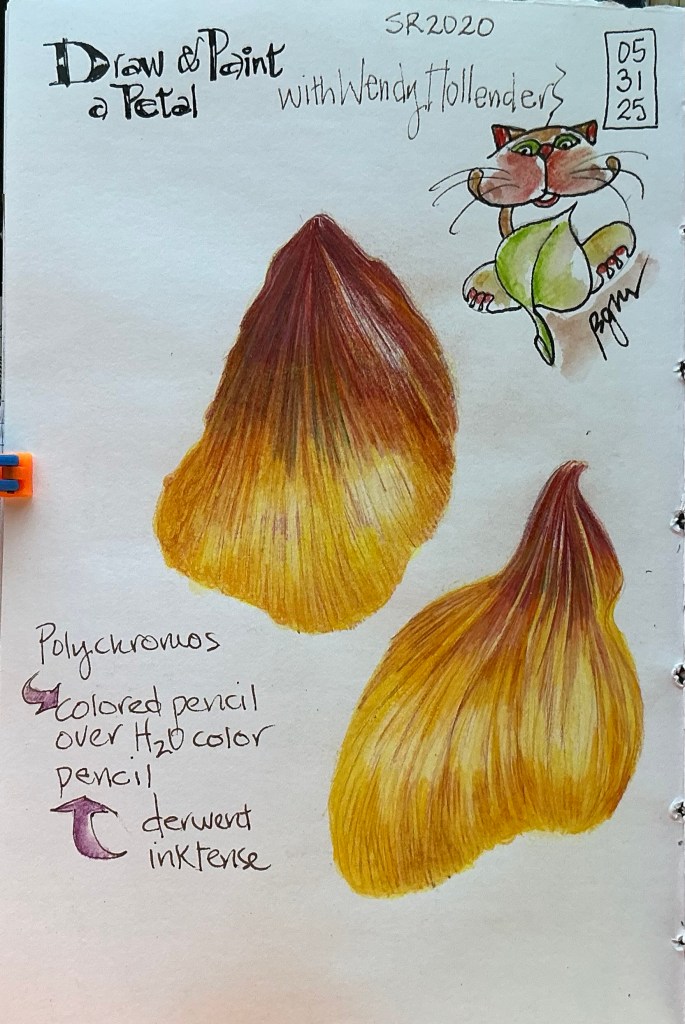

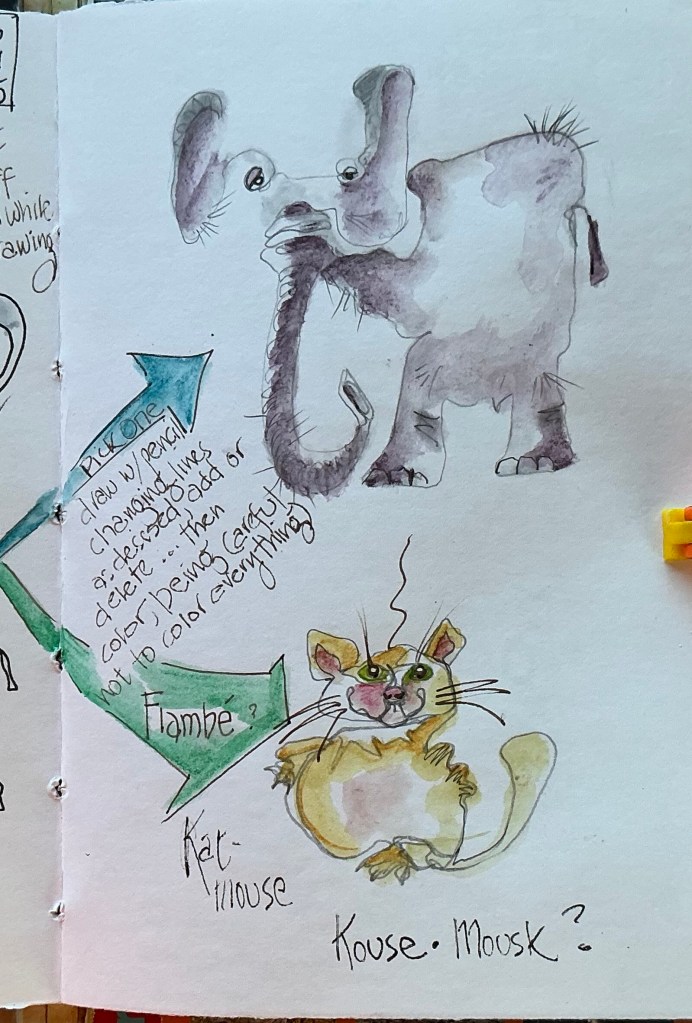

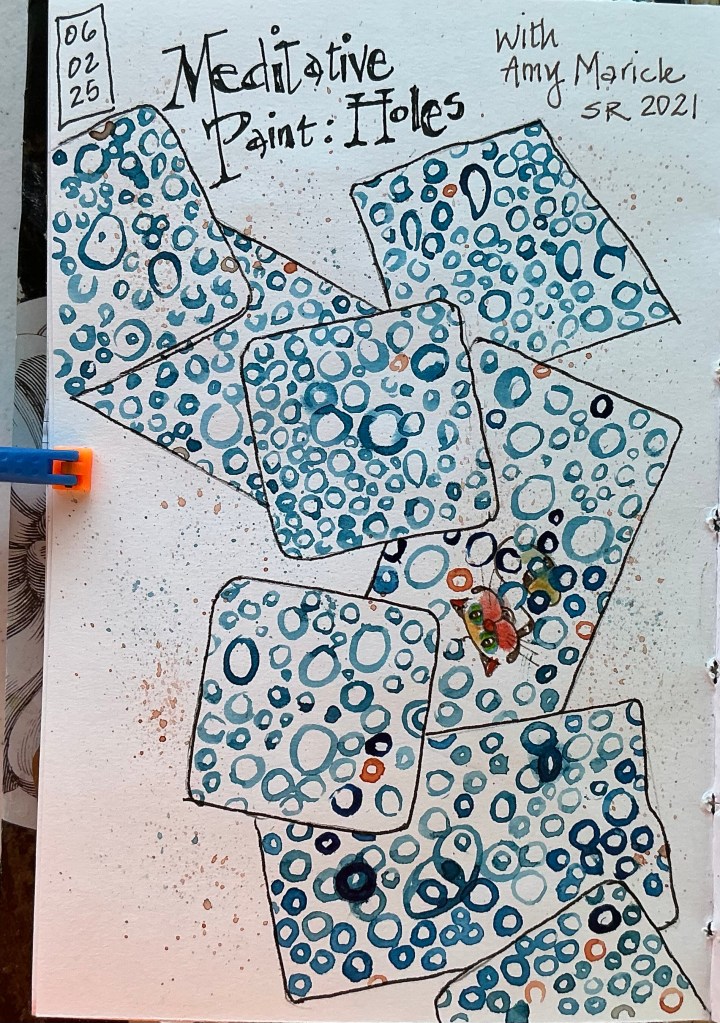

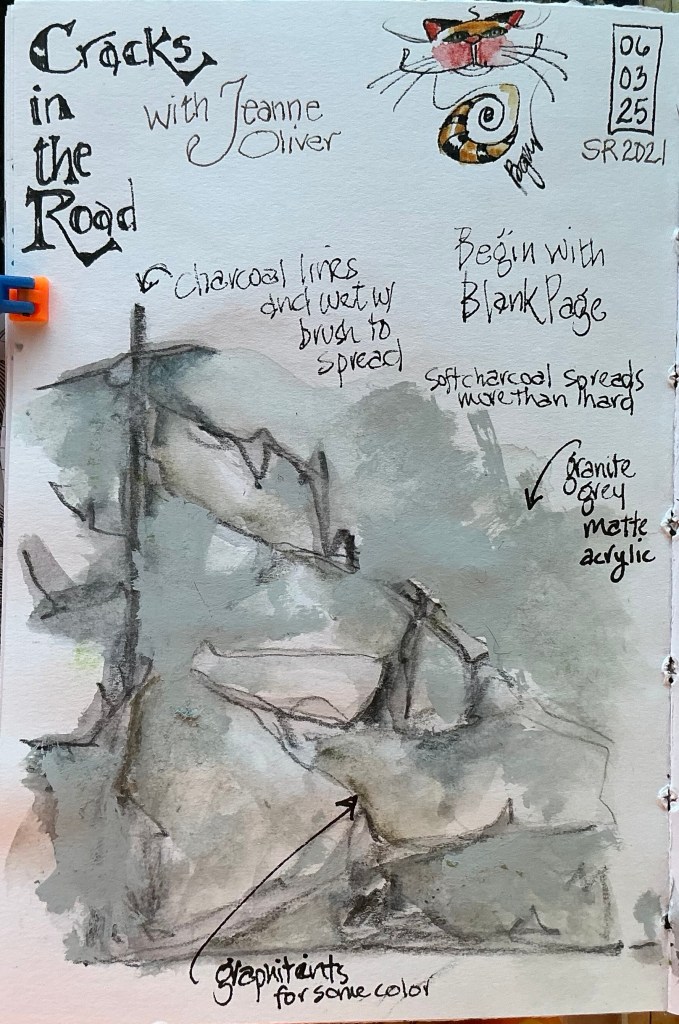

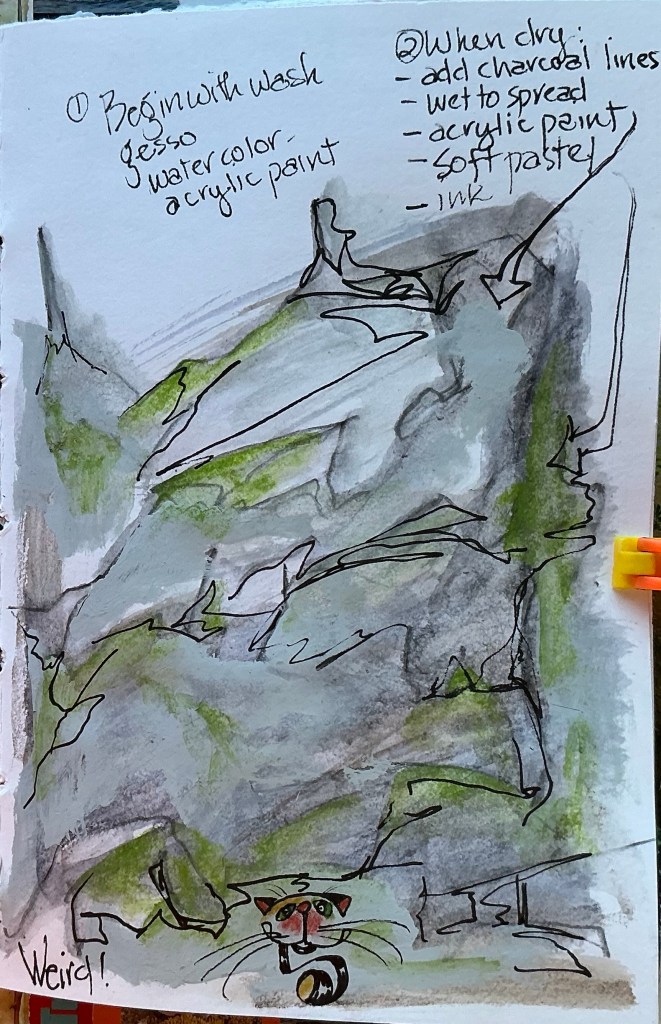

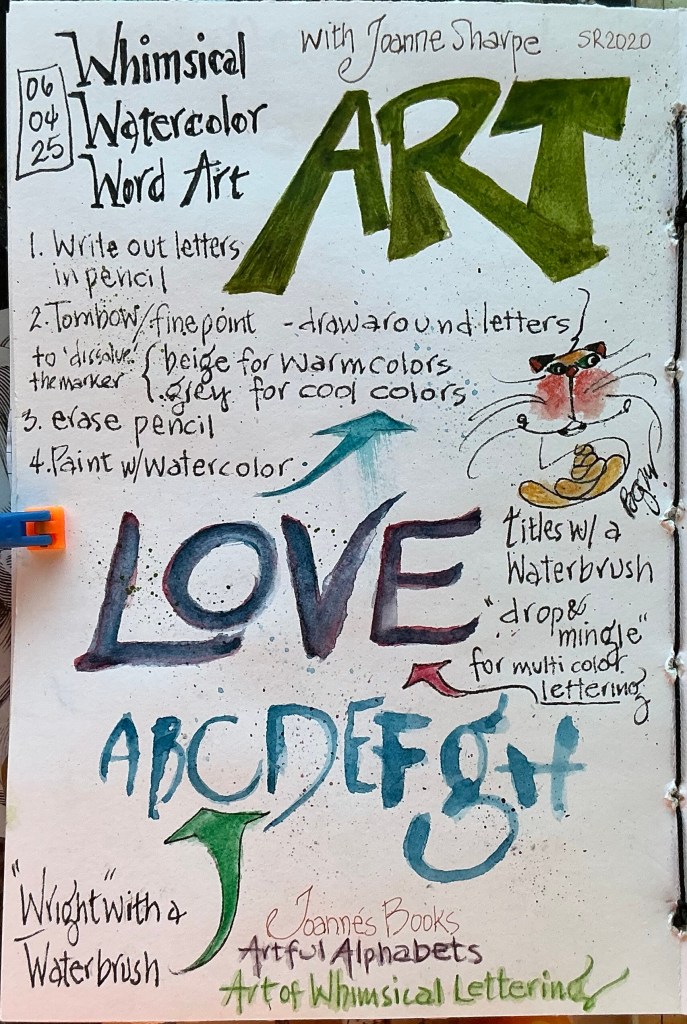

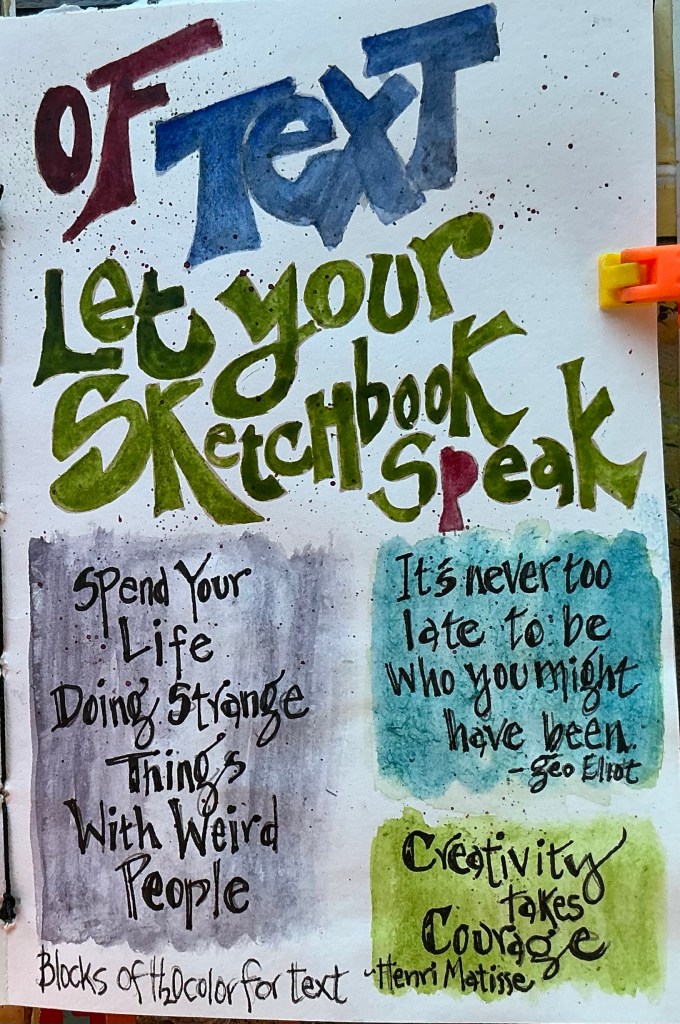

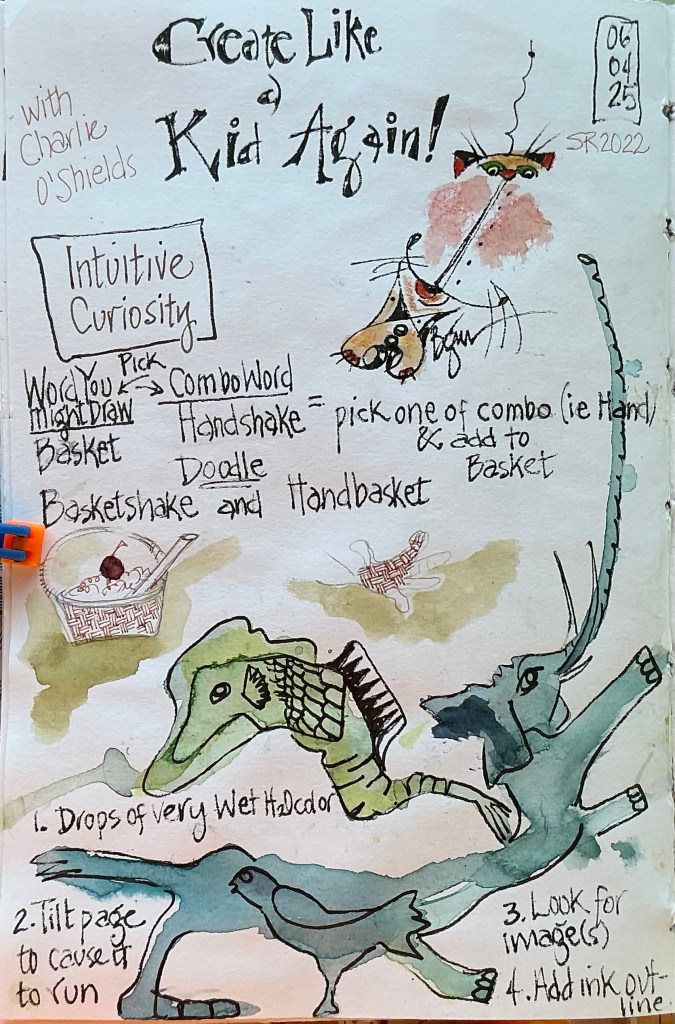

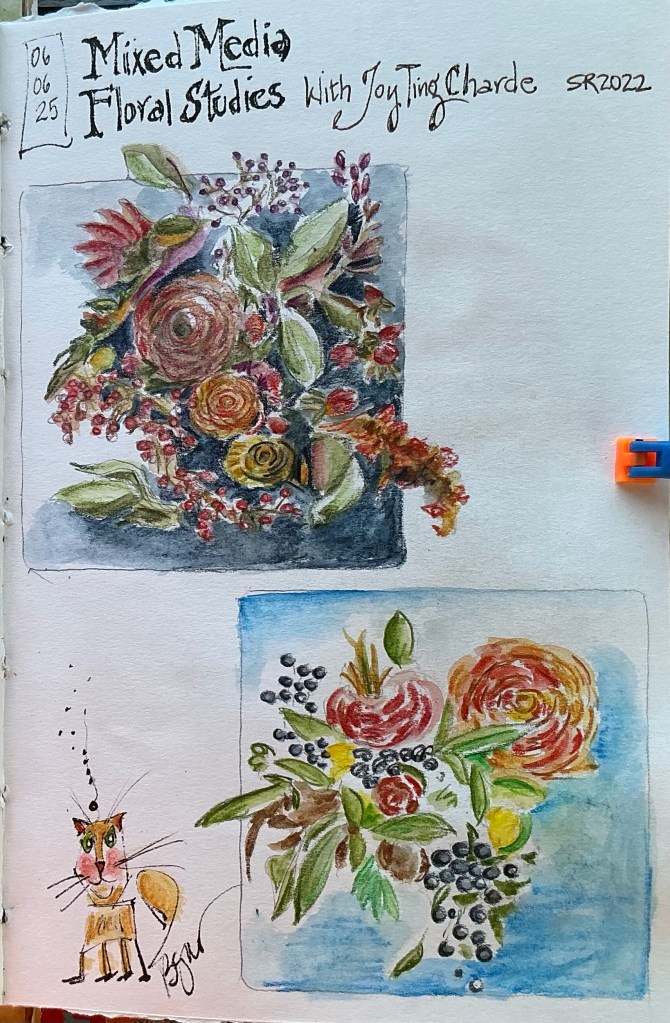

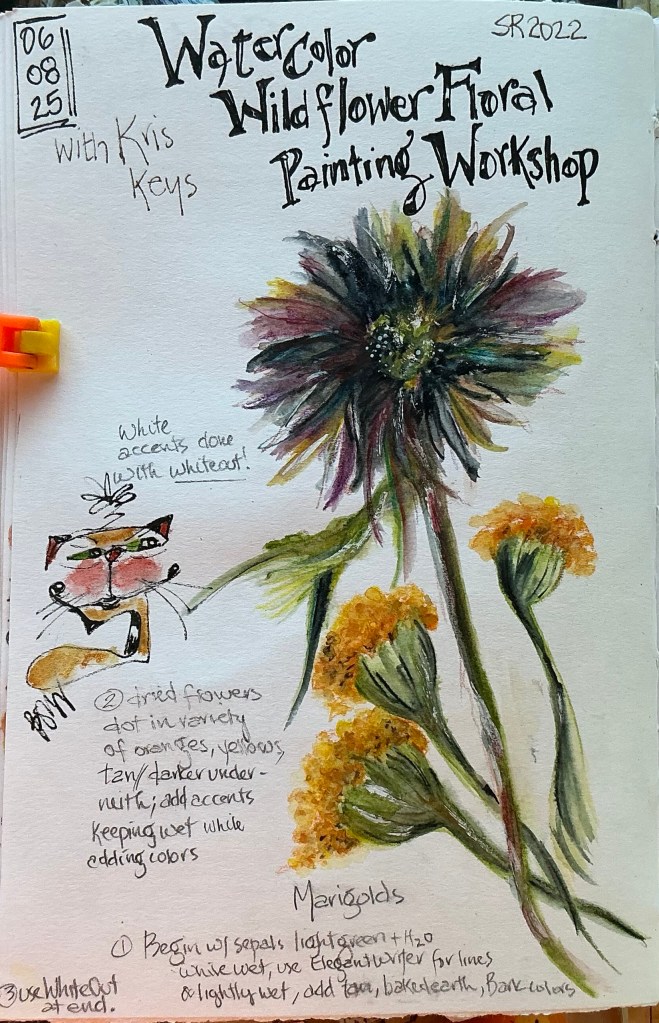

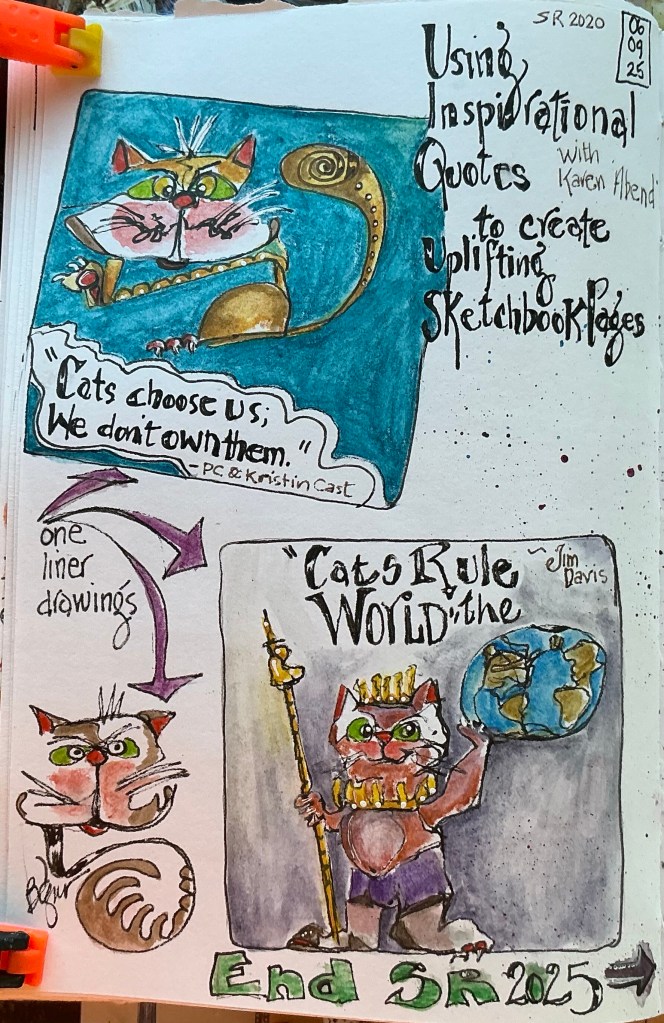

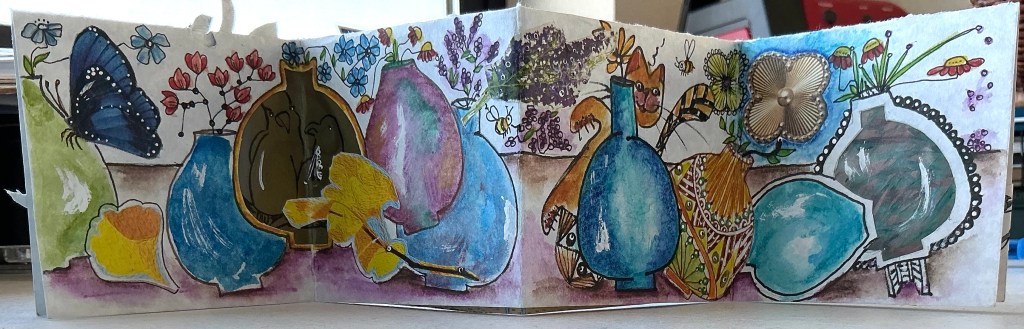

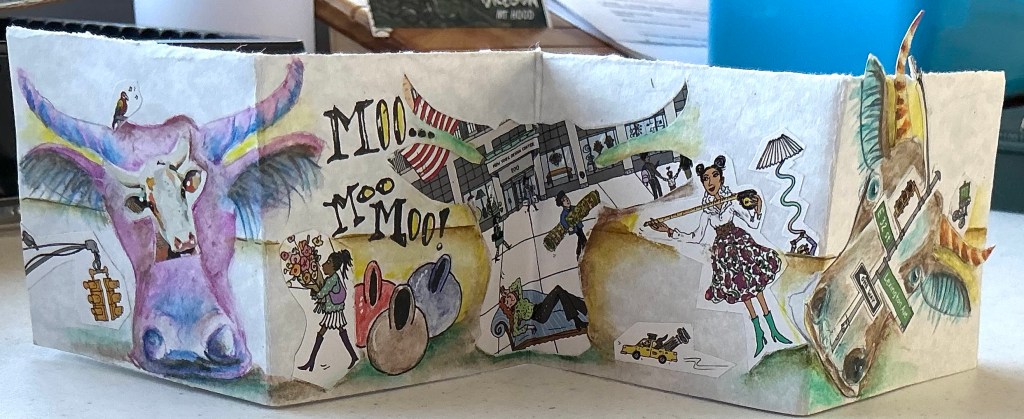

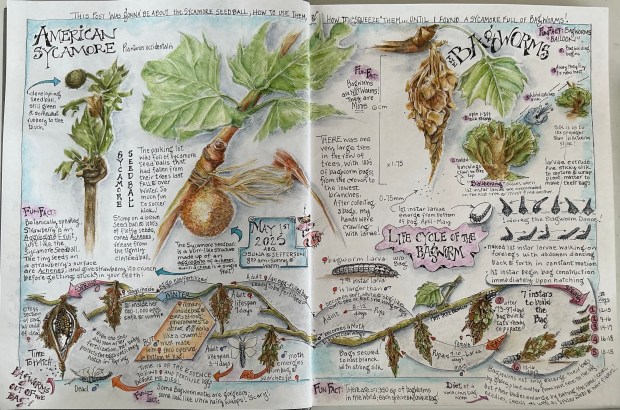

For more tidbits about Red Barberry, browse the text and illustrations displayed on my journal pages. Hope you enjoyed this post.

As always, thanks for stopping by!

P.S. In case you’d like to know about the etymology of the name Berberis haematocarpa…… ‘Berberis’ is a Latinized form of the Arabian name ‘barbaris, for barberry. “Haematocarpa” means ‘blood-red fruit’ referring to the bright red berries produced by this shrub. The word is derived from the Greek words “haima” (blood) and “karpos” (fruit).